CM 0180 S

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

SPONSORED BY AGENCIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADIAN GOVERNMENTS

This publication is to be used primarily in support of instructing military personnel as part of the Defense Language Program (resident and nonresident). Inquiries concerning the use of materials, including requests for copies, should be addressed to:

Defense Language Institute

Foreign Language Center

Nonresident Training Division

Presidio of Monterey, CA 93944-5006

Topics in the areas of politics, international relations, mores, etc., which may be considered as controversial from some points of view, are sometimes included in the language instruction for DLIFLC students since military personnel may find themselves in positions where a clear understanding of conversations or written materials of this nature will be essential to their mission. The presence of controversial statements-whether real òr apparent-in DLIFLC materials should not be construed as representing the opinions of the writers, the DLIFLC, or the Department of Defense.

Actual brand names and businesses are sometimes cited in DLIFLC instructional materials to provide instruction in pronunciations and meanings. The selection of such proprietary terms and names is based solely on their value for instruction in the language. It does not constitute endorsement of any product or commercial enterprise, nor is it intended to invite a comparison with other brand names and businesses not mentioned.

In DLIFLC publications, the words he, him, and/or his denote both masculine and feminine genders. This statement does not apply to translations of foreign language texts.

The DLIFLC may not have full rights to the materials it produces. Purchase by the customer does net constitute authorization for reproduction, resale, or showing for profit. Generally, products distributed by the DLIFLC may be used in any not-for-profit setting without prior approval from the DLIFLC.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach originated in an interagency conference held at the Foreign Service Institute in August 1973 to address the need generally felt in the U«S. Government language training community for improving and updating Chinese materials, to reflect current usage in Beijing and Taipei•

The conference resolved to develop materials which were flexible enough in form and content to meet the requirements of a wide range of government agencies and academic institutions.

A Project Board was established consisting of representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency Language Learning Center, the Defense Language Institute, the State Departmentfs Foreign Service Institute, the Cryptologic School of the National Security Agency, and the U.S. Office of Education, later joined "by the Canadian Forces Foreign Language School. The representatives have included Arthur T. McNeill, John Hopkins» and John Boag (CIA); Colonel John F. Elder III, Joseph C. Hutchinson, Ivy Gibian, and Major Bernard Muller-Thym (DLI); James R. Frith and John B. Ratliff III (FSI);

Kazuo Shitaaia (NSA); Richard T. Thompson and Julia Petrov (OE); and Lieutenant Colonel George Kozoriz (CFFLS).

The Project Board set up the Chinese Core Curriculum Project in 197^ in space provided at the Foreign Service Institute. Each of the six U.S. and CaQadian government agencies provided funds and other assistance.

Gerard P. Kok was appointed project coordinator, and a planning council was formed consisting of Mr. Kok, Frances Li of the Defense Language Institute, Patricia 0*Connor of the University of Texas, Earl M. Rickerson of the Language Learning Center, and James Wrenn of Brown University. In the fall of 1977* Lucille A. Barale vas appointed deputy project coordinator• David W. Dellinger of the Language Learning Center and Charles R. Sheehan of the Foreign Service Institute also served on the planning council and contributed material to the project. The planning council drew up the original overall design for the materials and met regularly to review their development•

Writers for the first half of the materials vere John H. T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale, and rioberta S. Barry, who worked in close cooperation with the planning council and with the Chinese staff of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Harvey developed the instructional formats of the comprehension and production self-study materials 9 and also designed the communica-tìon-'based classroom activities and wrote the teacherguides. Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry wrote the tape scripts and the student text.

By 19了8 Thomas E. Madden and Susan C. Pola had joined the staff. Led by Ms. Barale, they have worked as a team to produce the materials subsequent to ^fodule 6.

All Chinese language material was prepared or selected by Chuan 0. Chao, Ying-chi Chen, Hsiao-Jung Chi, Eva Diao, Jan Hu, Tsung-mi Li, and Yunhui C. Yang, assisted for part of the time by Chieh-fang Ou Lee, Ying-ming Chen, and Joseph Yu Hsu Wang. Anna Affholder, Mei-li Chen, and Henry Khuo helped in the preparation of a preliminary corpus of dialogues.

Administrative assistance was provided at various times by Vincent Basciano, Lisa A. Bovden, Jill W. ELlis,Donna Fong, Renee T. C. l^iang,

Thomas E. Madden, Susan C. Pola, and Kathleen Strype.

The production of tape recordings vas directed by Jose M. Ramirez of the Foreign Service Institute Recording Studio. The Chinese script vas voiced *by Ms. Chao, Ms. Chen, Mr. Chen, Ms. Diao, Ms. Hu, Mr. Khuo, Mr. Li, and Ms. Yang. The English script was read 切 Ms. Barale, Ms. Barry,

Mr. Basciano, Ms. Ellis, Ms. Pola, and Ms. Strype.

The graphics were produced by John McClelland of the Foreign Service Institute Audio-Visual staff, under the general supervision of Joseph A. Sadote, Chief of Audio-Visual.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach vas field-tested with the cooperation of Brown University; the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center; the Foreign Service Institute; the Language Learning Center; the United States Air Force Academy; the University of Illinois; and the University of Virginia.

Colonel Samuel L. Stapleton and Colonel Thomas G. Foster, Commandants of the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center, authorized the DLIFLC support necessary for preparation of this edition of the course materials. This support included coordination, graphic arts, editing, typing, proofreading, printing, and materials necessary to carry out these tasks.

Introduction

Section I: About the Course...................1

Section II: Background Notes...................8

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION

Objectives........................ . . . . 16

List of Tapes...........................17

Target Lists ........................... 18

UNIT 1

Introduction.........................22

Reference List........ • • • .............26

Vocabulary..........................27

Reference Notes...................* .... 28

Full names and surnames Titles and terms of address Drills............................32

UNIT 2

Introduction ......................... 3U

Reference List........................35

Vocabulary..........................36

Reference Notes ........................ 37

Given names Yes/no questions Negative statements Greetings

Drills........................ .... kl

UNIT 3

Introduction ......................... U8

Reference List........................“9

Vocabulary....................... . . .

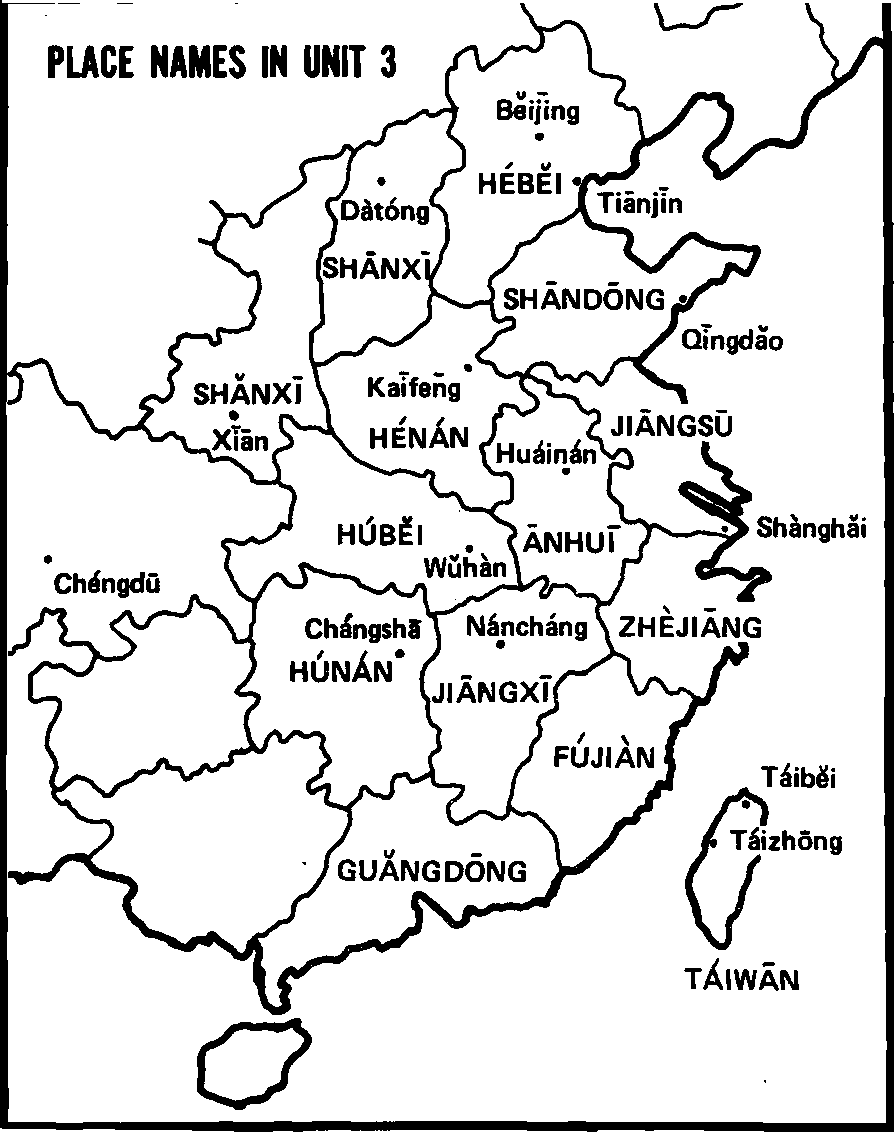

Unit Map...........................52

Reference Notes ........................ 53

Nationality

Home state, province, and city Drills............................56

UNIT U

Introduction ......................... 60

Reference List........................6l

Vocabulary..........................62

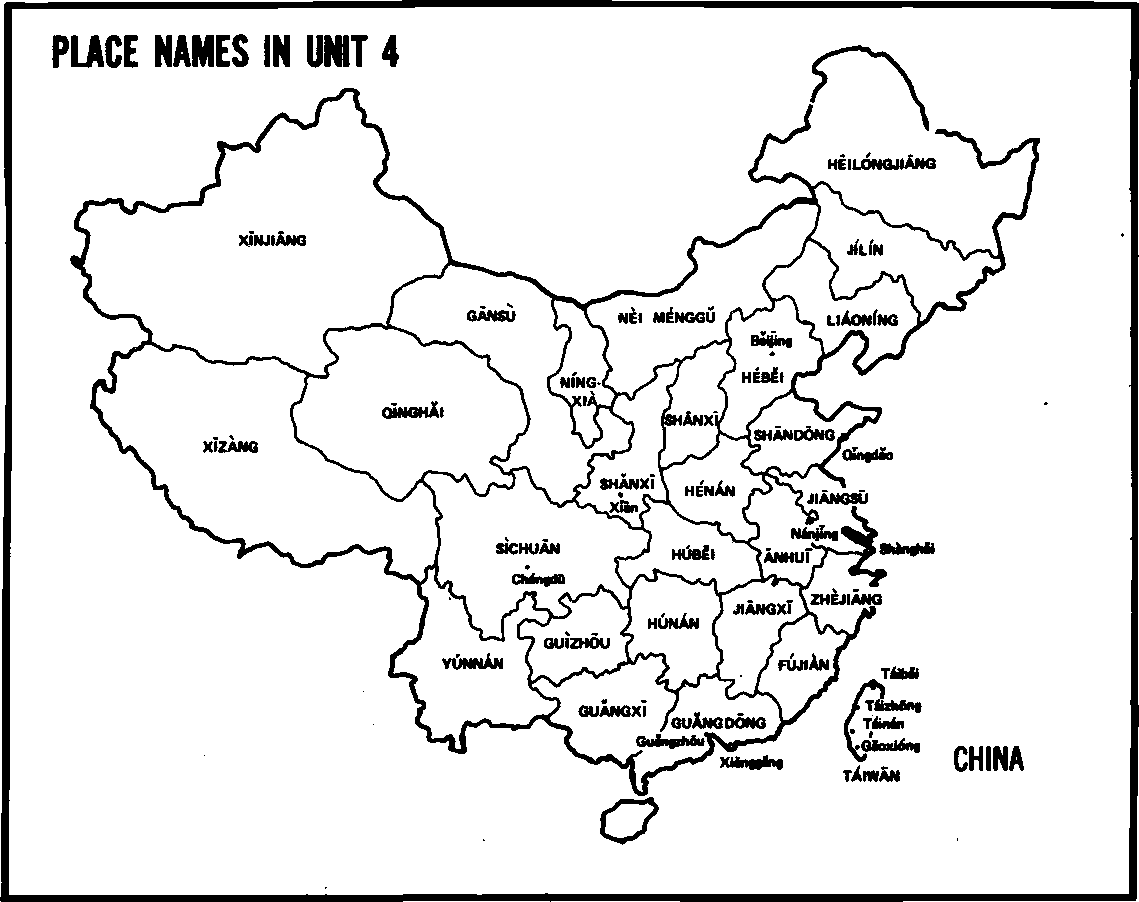

Unit Map...........................63

Reference Notes....................... • 6U

Location of people and places Where people's families are from

Drills...........................69

Criterion Test Sample ......................75

Appendices

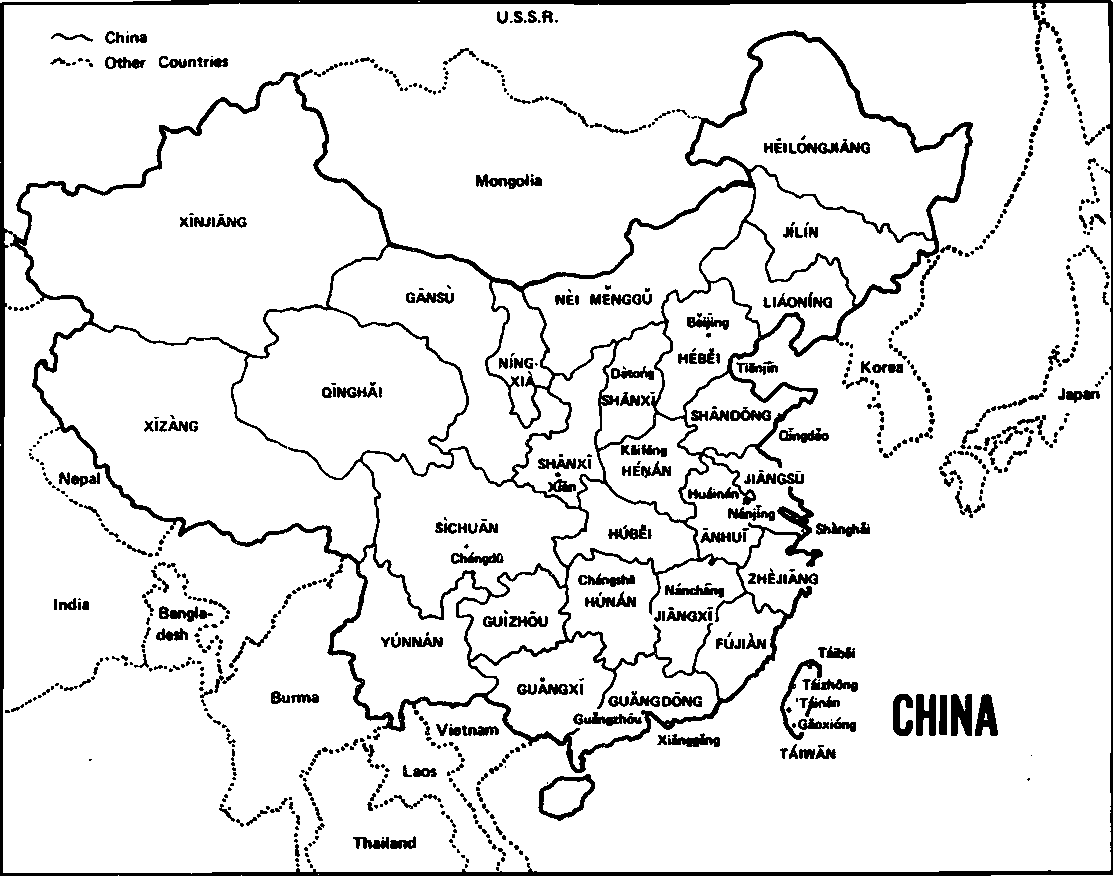

I. Map of China......................80

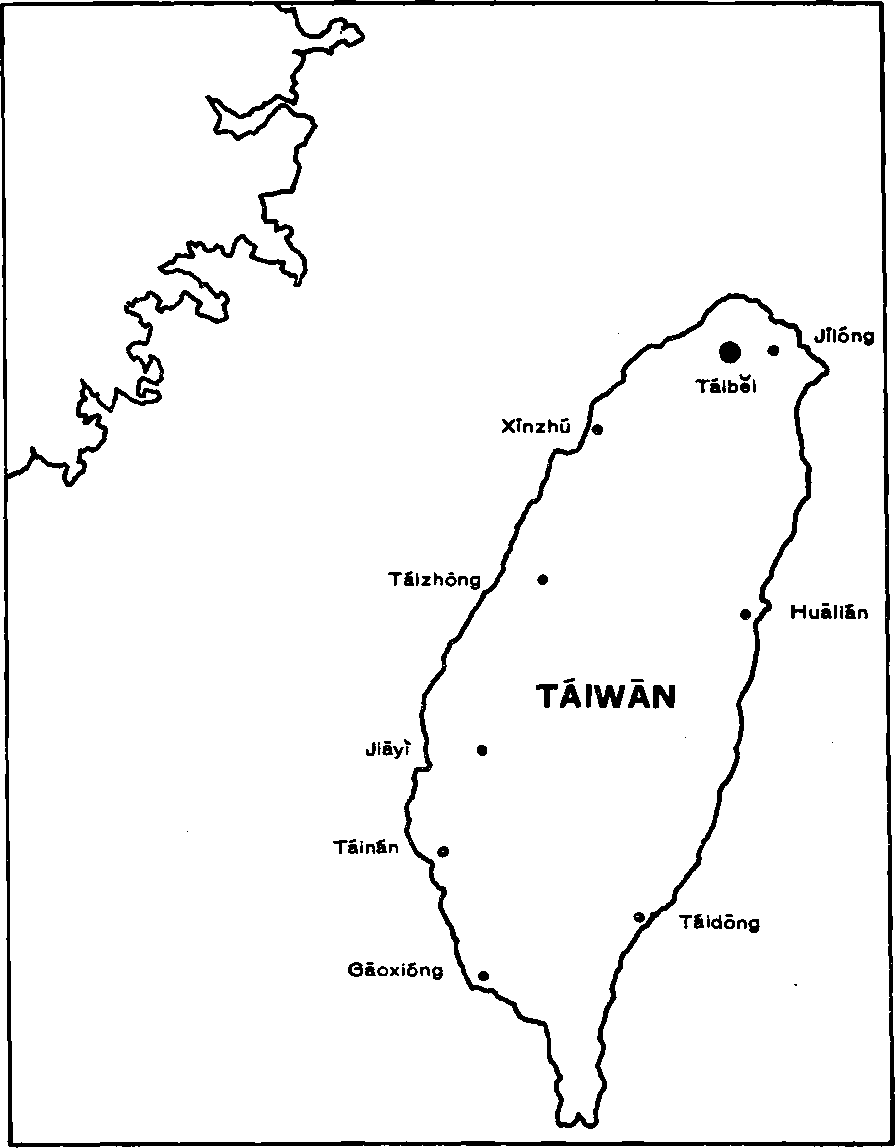

II • Map of Taiwan......................8l

III. Countries and Regions..................82

IV, American States.....................8U

V. Canadian Provinces................. • • 85

VI* ConiDon Chinese Names..................86

VII, Chinese Provinces ........................................87

VIII, Chinese Cities.....................88

MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

Objectives...........................89

List of Tapes..........................90

Target Lists..........................91

UNIT 1

Introduction........................99

Reference List.......................99

Vocabulary........................100

Reference Notes ...................... 101

Where people are staying (hotels)

Short answers

The question word neige "which?"

Drills..........................105

UNIT 2

Introduction ......................Ill

Reference List......................、112

Vocabulary........................llU

Reference Rotes ......................115

Where people are staying (houses)

Where people are working Addresses The marker de The marker ba The prepositional verb zài Drills..........~...............120

UNIT 3

Introduction.......................12 了

Reference List .......................128

Vocabulary........................130

Reference Notes ..................... 131

Members of a family

The plural ending -men

The question word jĭ- !fhow many”

The adverb dou all Several ways to express nandM Drills • • ............... • • ..........136

[JNIT k

Introduction...................... • • • 1 从

Reference List.....•...................1^5

Vocabulary..........................1^6

Reference Notes ................ ••••••• 1^7

Arrival and departure times The marker le The shi…de construction Drills............................153

UNIT 5

Introduction.........................1^2

Reference List........................163

Vocatxilary..........................165

Reference Notes ....................... 166

Date and place of birth Days of the week Ages

The marker le for new situations Drills . . . . ....................1T1

UNIT 6

Introduction....................... • • 1T8

Reference List • • • ...............................179

Vocabulary........................ . • 180

Reference Notes ................

Duration phrases

The marker le for completion

The "double le” construction

The marker guo

Action verts

State verbs

Drills.....................188

UBIT 7

Introduction. ......................* • • 196

Reference List..................... • • • 19了

Vocabulary.......... ................199

Reference Notes ............ ••••••«••*• 200

Where someone vorks

Where and vhat someone has studied

What languages someone can speak

Auxiliary verbs

General objects

Drills............................20U

UNIT 8

Introduction.........................213

Reference List........................2lū

Vocabulary..........................215

Reference Notes.......................216

More on duration phrases

The marker le for nev situations in negative sentences Military titles and branches of service The marker ne Process verbs

Drills............................223

This course is designed to give you a practical command of spoken Standard Chinese. You will learn both to understand and to speak it. Although Standard Chinese is one language, there are differences betveen the particular form it takes in Beijing and the form it takes in the rest of the country. There are also, of course, significant nonlinguistic differences between regions of the country. Reflecting these regional differences, the settings for most conversations are Beijing and Taipei.

This course represents a nev approach to the teaching of foreign languages. In many ways it redefines the roles of teacher and student, of classvork and homework, and of text and tape. Here is what you should

expect:

The focus is on communicating in Chinese in practical situations—the obvious ones you will encounter upon arriving in China. You vill be communicating in Chinese most of the time you are in class. You will not always "be talking about real situations, "but you will almost alvays be purposefully exchanging information in Chinese.

This focus on communicating means that the teacher is first of all your conversational partner. Anything that forces hizn^ back into the traditional roles of lecturer and drillmastar limits your opportunity to interact with a speaker of the Chinese language and to experience the language in its full spontaneity, flexibility5 and responsiveness.

Using class time for communicating, you will complete other course activities out of class whenever possible. This is vhat the tapes are for. They introduce the nev material of each unit and give you as much additional practice as possible vithout a conversational partner.

The texts suminarize and supplement the tapes, vhìch take you through new material step "by step and then give you intensive practice on vhat you have covered. In this course you will spend almost all your time listening to Chinese and saying things in Chinese, either vith the tapes or in class.

Hov the Course Is Organized

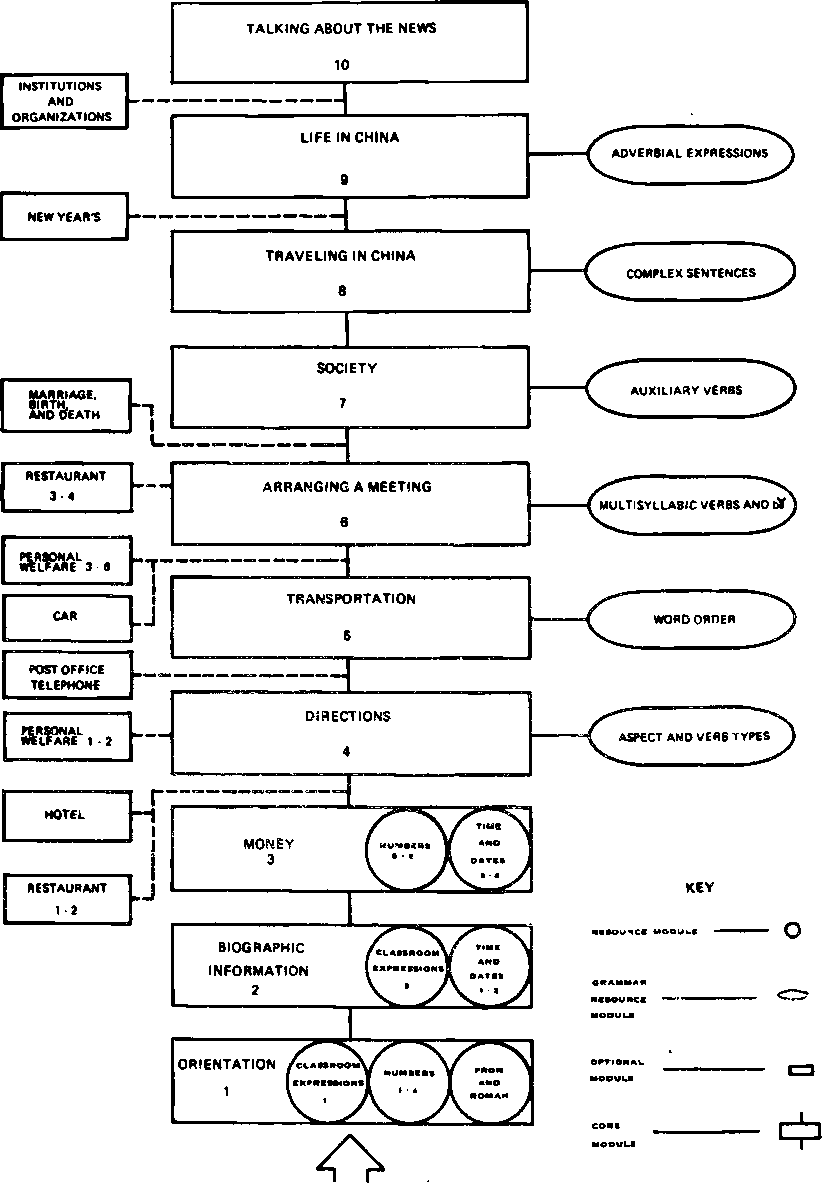

The subtitle of this course, "A Modular Approach," refers to overall organization of the materials into MODULES which focus on particular situations or language topics and which allow a certain amount of choice as to vhat is taught and in what order. To highlight equally significant features of the course, the subtitle could Just as well have "been ”A Situational Approach," 11A Taped-Input Approach," or 11A Communicative Approach/1

|

Ten situational modules form the core of the course: | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Each core module consists of tapes, a student textbook, and a workbook. |

In addition to the ten CORE modules, ther.e are also RESOURCE modules and OPTIONAL modules*. Resource modules teach particular systems in the language, such as numbers and dates. As you proceed through a situational core module, you vill occasionally take time out to study part of a resource module. (You vill begin the first* three of these while studying the Orientation Module.)

|

PRONUNCIATION AND ROMANIZATION (P&R) |

The sound system of Chinese and the Pinyin system of romanization. |

|

NUMBERS (NUM) |

Numbers up to five digits. |

|

CLASSROOM EXPRESSIONS (CE) |

Expressions "basic to the classroom learning situation. |

|

TIME AND DATES (T&D) |

Dates, days of the week, clock time, parts of the day. |

|

GRAMMAR |

Aspect and verb types, word order, multisyllabic verbs and auxiliary verbs „ complex sentences, adverbial expressions. |

Each module consists of tapes and a student texfbook.

The eight optional modules focus on particular situations:

RESTAURANT (RST)

HOTEL (HTL)

PERSONAL WELFARE (WLF)

POST OFFICE AND TELEPHONE (PST/TEL)

CAB (CAB)

CUSTOMS SURROUNDING MARRIAGE, BIRTH, MD DEATH {MED)

NEW YEAR^ CELEBRATION (NYH)

INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS (l&0)

Each module consists of tapes and a student textbook. These optional modules may be used at any time after certain core modules,

The diagram on page 紅 shows hov the core modules9 optional modules,and resource modules fit together in the course. Resource modules are shown where study should begin. Optional modules are shovn where they may be introduced.

A MODULAR APPROACH

Inside a Core Module

Each core module has from four to eight units. A module also includes

Objectives: The module objectives are listed at the beginning of the text for each module. Read these before starting work on the first unit to fix in your mind what you are trying to accomplish and what you vill have to do to pass the test at the end of the module.

Target Lists: These follow the objectives in the text. They summarize the language content of each unit in the form of typical questions and answers on the topic of that unit. Each sentence is given both in roman-ized Chinese and in English. Turn to the appropriate Target List before, during, or after your work on a unit, whenever you need to pull together what is in the unit.

Review Tapes (R-l): The Target List sentences are given on these tapes. Except in the short Orientation Module, there are two R-l tapes for each module•

Criterion Test: After studying each module, you will Test to find out which module objectives you have met to work on "before "beginning to study another module.

take a Criterion and which you need

Inside a Unit

Here is what you vill be doing in each unit. First, you will vork

through two tapes:

1. Comprehension Tape 1 (C-l): This tape introduces all the new words and structures in the unit and lets you hear them in the context of short conversational exchanges. It then works them into other short conversations and longer passages for listening practice, and finally reviews them in the Target List sentences. Your goal when using the tape is to under-stand all the Target List sentences for the unit.

2. Production Tape 1 (P-l): This tape gives you practice in pronouncing the new words and in saying the sentences you learned to understand on the C-l tape. Your goal when using the P-l tape is to "be able to produce any of the Target List sentences in Chine” when given the English equivalent.

The C-l and P-l tapes,not accompanied by workbooks, are ”portable,’ in the sense that they do not tie you down to your desk. However, there are some written materials for each unit which you will need to work into your study routine. A text Reference List at the beginning of each unit contains the sentences from the C-l and P-l tapes. It includes both the Chinese sentences and their English equivalents. The text Reference Notes restate and expand the comments made on the C-l and P-l tapes concerning grammar, vo-cabulary, pronunciation, and culture.

After you have worked with the C-l and P-l tapes, you go on to two class activities: 3. Target List Review: In this first class activity of the unit, you find out how well you learned the C-l and P-l sentences. The teacher checks your understanding and production of the Target List sentences. He also presents any additional required vocabulary items, found at the end of the Target List, which were not on the C-l and P-l tapes.

U. Structural Buildup: During this class activity, you work on your understanding and control of the new structures in the unit. You respond to questions from your teacher about situations illustrated on a chalkboard or explained in other ways.

After these activities, your teacher may want you to spend some time vorking on the drills for the unit.

5. Drill Tape: This tape takes you through various types of drills based on the Target List sentences and on the additional required vocabulary.

6. Drills: The teacher may have you go over some or all of the drills in class, either to prepare for work with the tape, to review the tape, or to replace it.

Next,you use two more tapes. These tapes vill give you as much additional practice as possible outside of class.

7. Comprehension Tape 2 (C-2): This tape provides advanced listening practice with exercises containing long, varied passages which fully exploit the possibilities of the material covered. In the C-2 Workbook you answer questions about the passages.

8. Production Tape 2 (P-2): This tape resembles the Structural Buildup

in that you practice using the new structures of the unit in various situations. The P-2 Workbook provides instructions and displays of information for each exercise.

Following work on these two tapes, you take part in two class activities:

9. Exercise Review: The teacher reviews the exercises of the C-2 tape by reading or playing passages from the tape and questioning you on them. He reviews the exercises of the P-2 tape by questioning you on information displays in the P-2 Workbook.

10. Communication Activities: Here you use what you have learned in the unit for the purposeful exchange of information. Both fictitious situations (in Communication Games) and real-world situations involving you and your classmates (in ”intervievs”) are used.

|

Materials and Activities for a Unit | |||||||||||||||

|

Wen wu Temple in central Taiwan (courtesy of Thomas Madden)

SECTION II BACKGROUND NOTES: ABOUT CHINESE

The Chinese Languages

We find it perfectly natural to talk about a language called ”Chinese." We say, for example, that the people of China speak different dialects of Chinese, and that Confucius wrote in an ancient form of Chinese• On the other hand, we would never think of saying that the people of Italy,

France, Spain, and Portugal speak dialects of one language, and that Julius Caesar wrote in an ancient form of that language. But the facts are almost exactly parallel.

Therefore, in terms of vhat we think of as a language when closer to home, "Chinese” is not one language, but a family of languages. The language of Confucius is partway up the trunk of the family tree. Like Latin, it lived on as a literary language long after its death as a spoken language in popular use. The seven modern languages of China, traditionally known as the "dialects," are the branches of the tree. They share as strong a family resemblance as do Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese, and are about as different from one another.

The predominant language of China is now known as Pŭtonghuà, or "Standard Chinese” (literally ”the common speech”). The more traditional term, still used in Taiwan, is Guĕyŭ^ or "Mandarin” (literally ”the national language"). Standard Chinese is spoken natively by almost tvo-thirds of the population of China and throughout the greater part of the country.

The term "Standard Chinese" is often used more narrowly to refer to the true national language which is emerging. This language, which is already the language of all national broadcasting, is based primarily on the 'Peking dialect, but takes in elements from other dialects of Standard Chinese and even from other Chinese languages. Like many national languages, it is more widely understood than spoken, and is often spoken with some concessions to local speech, particularly in pronunciation.

The Chinese languages and their dialects differ far more in pronunciation than in grammar and vocabulary. What distinguishes Standard Chinese most from the other Chinese languages, for example» is that it has the fewest tones and the fevest final consonants.

The remaining six Chinese languages, spoken by approximately a quarter of the population of China, are tightly grouped in the southeast, telov the Yangtze River. The six are: the Wu group (Wu), which includes the ”Shanghai dialect”; Hunanese (Xiang); the "Kiangsi dialect" (Gan); Cantonese (Yuè), the language of Guăngdōng, widely spoken in Chinese communities in the United States; Fukienese (Mĭn), a variant of which is spoken by a majority

on Taiwan and hence called Taiwanese; and Hakka (Kè.Hā), spoken in a belt above the Cantonese area, as well as by a minority on Taiwan. Cantonese, Fukienese, and Hakka are also widely spoken throughout Southeast Asia.

There are minority ethnic groups in China who speak non-Chinese languages • Some of these, such as Tibetan, are distantly related to the Chinese languages. Others, such as Mongolian, are entirely unrelated.

Some Characteristics of Chinese

To us, perhaps the roost striking feature of spoken Chinese is the use of variation in tone ("tones”) to distinguish the different meanings of syllables which vould otherwise sound alike. All languages» and Chinese is no exception, znaKe use of sentence intonation to indicate how whole sentences are to "be understood. In English, for example, the rising pattern in "He’s gone?" tells us that the sentence is meant as a question.

The Chinese tones, however, are quite a different matter. They "belong to individual syllables, not to the sentence as a whole. An inherent part of each Standard Chinese syllable is one of four distinctive tones. The tone does just as much to distinguish the syllable as do the consonants and vowels. For example, the only difference between the verb ”to buy,'f and the verb ’’to sell, mài, is the Low tone (w) and the Falling tone (v). And ye.t these vords are Just as distinguishable as our words ”"buy” and Tlguy," or ”"buy” and ’’boy•” Apart from the tones, the sound system of Standard Chinese is no more different from English than French is.

Word formation in Standard Chinese is relatively simple. For one thing, there are no conjugations such as are found in many European languages . Chinese verbs have fever forms than English verbs, and nowhere near as many irregularities • Chinese grainmar relies heavily on word order, and often the word order is the same as in English. For these reasons Chinese is not as difficult for Americans to learn to speak as one might think.

It is often said that Chinese is a monosyllabic language. This notion contains a good deal of truth. It has been found that, on the average, every other vord in ordinary conversation is a single-syllable word. Moreover, although most words in the dictionary have two syllables, and some have more,these vords can almost alvays be broken down into singlesyllable units of meaning, many of which can stand alone as words.

Written Chinese

Most languages with which ve are familiar are written with an alphabet. The letters may "be different from ours, as in the Greek alphabet, *but the principle is the same: one letter for each consonant or vovel sound, more or less. Chinese, however, is written with "characters" which stand for whole syllables--in fact, for yhole syllables vith particular meanings. Although there are only about thirteen hundred phonetically distinct syllables in standard Chinese, there are several thousand Chinese characters in everyday use, essentially one for each single-syllable unit of meaning. This means that many words have the same pronunciation "but are written with different characters, as tiān, ”sky,"天,and tiān, "to add,” "to increase," 添. Chinese characters are often referred to as Tfideographs,which suggests that they stand directly for ideas. But this is misleading. It is better to think of them as standing for the meaningful syllables of the spoken language.

Minimal literacy in Chinese calls for knowing about a thousand characters .These thousand characters» in combination, give a reading vocabulary of several thousand words. Full literacy calls for knowing some three thousand characters. In order to reduce the amount of time needed to learn characters, there has been a vast extension in the People1s Republic of China (PRC) of the principle of character simplification, which has reduced the average number of strokes per character by half.

During the past century, various systems have been proposed for representing the sounds of Chinese with letters of the Roman alphabet. One of these romanizations, Hànyŭ Pĭnyín (literally ”Chinese Language Spelling, generally called nPinyin in English), has "been adopted officially in the PRC, with the short-term goal of teaching all students the Standard Chinese pronunciation of characters. A long-range goal is the use of Pinyin for written communication throu^iout the country. This is not possible, of course, until speakers across the nation have uniform pronunciations of Standard Chinese. For the time being, characterss which represent meaning, not pronunciation, are still the most widely accepted way of coaaaunicating in writing.

Pinyin uses all of the letters in our alphabet except v, and adds the letter u. The spellings of some of the consonant sounds are rather arbitrary from our point of view, but for every consonant sound there is only one letter or one combination of letters, and vice versa. You vill find that each vowel letter can stand for different vowel sounds, depending on what letters precede or follow it in the syllable • The four tones are indicated by accent marks over the vowels, and the Neutral tone by the absence of an accent mark:

|

High: |

mā |

Falling: mà |

|

Rising: |

má |

Neutral: ma |

|

Low: |

ma |

One reason often given for the retention of characters is that they can be read, with the local pronunciation, by speakers of all the Chinese languages. Probably a stronger reason for retaining them is that the characters help keep alive distinctions of meaning between words, and connections of meaning between vords, which are fading in the spoken language. On the other hand, a Cantonese cotild learn to speak Standard Chinese, and read it alphabetically, at least as easily as he can learn several thousand characters.

Pinyin is used throughout this course to provide a simple written representation of pronunciation. The characters, which are chiefly responsible for the reputation of Chinese as a difficult language, are taught separately.

BACKGROUND NOTES: ABOUT CHINESE CHARACTERS

Each Chinese character is written as a fixed sequence of strokes.

There are very few "basic types of strokes, each with its ovn prescribed direction, length, and contour. The dynamics of these strokes as written with a "brush, the classical writing instrument, shov up clearly even in printed characters. You can tell from the varying thickness of the stroke how tlje brush met the paper, hov it swooped, and how it lifted; these effects are largely lost in characters vritten with a "ball-point pen.

The sequence of strokes is of particular importance. Let's take the character for "moutli,” pronounced kou. Here it is as normally written, vith the order and directions of the strokes indicated.

If the character is written rapidly, in "running-style writing,M one stroke glides into the next, like this.

If the strokes were written in any but the proper order, quite different distortions would take place as each stroke reflected the last and anticipated the next, and the character would be illegible.

The earliest surviving Chinese characters, inscribed on the Shang Dynasty "oracle bones" of about 1500 B.C., already included characters that vent beyond simple pictorial representation. There are some characters in use today which are pictorial, like the character for "mouth." There are also some which are directly symbolic, like our Roman numerals I, II, and III. (The characters for these numbers—the first numbers you learn in this course--are like the Roman numerals turned on their sides.) There are some which are indirectly symbolic, like our Arabic numerals 1,2, and 3. But the most common type of character is complex, consisting of two parts: a "phonetic, which suggests the pronunciation, and a ”radical,,’ which broadly characterizes the meaning. Letfs take the following character as an example.

This character means "ocean” and is pronounced yăng« The left side of the character, the three short strokes, is an abbreviation of a character which means "water” and is pronounced shuĭ. This is the "radical." It has been borrowed only for its meaning, "vater. The right side of the character above is a character which means "sheep” and is pronounced yang. This is the ”phonetic/’ It has been borrowed only for its sound value, yang.

A speaker of Chinese encountering the above character for the first time could probably figure out that the only Chinese word that sounds like yang and means something like fVater,? is the word yăng meaning "ocean,” We, as speakers of English9 might not "be able to figure it out. Moreover, phonetics and radicals seldom work as neatly as in this example. But we can still learn to make good use of these hints at sound and sense.

Many dictionaries classify characters in terms of the radicals.

According to one of the two dictionary systems used, there are 1了6 radicals; in the other system, there are 2lk. There are over a thousand phonetics。

Chinese has traditionally been vritten vertically, from top to bottom of the page, starting on the right-hand side, with the pages bound so that the first page is where ve would expect the last page to be* Nowadays, however, many Chinese publications paginate like Western publications, and the characters are written horizontally, from left to right。

BACKGROUND NOTES: ABOUT CHINESE PERSONAL NAMES AND TITLES

A Chinese personal name consists of two parts: a surname and a given name. There is no middle name. The order is the reverse of ours: surname first, given name last.

The most common pattern for Chinese names is a single二syllable surname followed by a two-syllaì)le given name: 1

Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung)

Zhōu Enlái (Chou En-lai)

Jiang Jièshí (Chiang Kai-shek)

Song Qìnglíng (Soong Chfing-lingMme Sun Yat-sen)

Song Mĕilíng (Soong Mei-iing--Mme Chiang Kai-shek)

It is not uncommon, however, for the given name to consist of a single syllable:

Zhŭ Dĕ (Chu Teh)

Lín Biāo (Lin Piao)

Hu Shi (Hu Shih)

Jiang Qĭng (Chiang Ch,ing—Mme Mao Tse-tung)

There are a few tvo-syllable surnames. These are usually followed by single-syllable given names:

Sĭmă Guang (Ssu-ma Kuang)

Ōuyáng Xiū (Ou-yang Hsiu)

Zhūgĕ Lìàng (Chu-ke Liang)

But two-syllable surnames may also be folloved by two-syllable given names:

Sĭmă Xiāngrú (Ssu-ma Hsiang-ju)

An exhaustive list of Chinese surnames includes several hundred written with a single character and several dozen written vith tvo characters.

Some single-syllable surnames sound exactly alike although written vith different characters, and to distinguish them, the Chinese nay occasionally have to describe the character or "write" it vith a finger on the palm of a hand. But the surnames that you are likely to encounter are fever than a hundred, and a handful of these are so common that they account for a good majority of China’s population.

Given names, as opposed to surnames, are not restricted to a limited list of characters, Menfs names are often but not always distinguishable from women1s; the difference, however, usually lies in the meaning of the characters and so is not readily apparent to the beginning student with a limited knowledge of characters.

Outside the People1s Republic the traditional system of titles is still in use. These titles closely parallel our own "Mr”” "Mrs•,” and ”Miss•” Notice, however, that all Chinese titles follow the name--either the full name or the surname alone—rather than preceding it.

The title "Mr•” is Xiānsheng.

MS Xiānsheng J4ă Mínglĭ Xiānsheng

The title "Mrs." is Tàitai. It follows the husband1s full name or surname alone.

MS Tàitai

MS Mínglĭ Tàitai

The title ”Miss” is XiSoJiĕ. The Ma familyfs grown daughter, Dĕfēn, would *be

Xiaojie Dĕfēn Xiăojiĕ

Ma

Mă

Even traditionally, outside the PeopleTs Republic, a married woman does not take her husband1s name in the same sense as in our culture. If Miss Fang Băolăn marries Mr. Ma Mínglĭ, she becomes Mrs, Mă Mínglĭ,but at the same time she remains Fang Băolán, She does not become Ma Băolán; there is no equivalent of ”Mrs. Mary Smith。” She may, however, add her husband?s surname to her own full name and refer to herself as Mă Fang Băolán. At work she is quite likely to continue as Miss Fang.

These customs regarding names are still observed by icany Chinese today in various parts of the world. The titles carry certain connotations, however, when used in the PRC today: Tàitai should not be used "because it designates that woman as a member of the leisure class. Xiao.lig should not be used because it carries the connotation of being from a rich family.

In the People's Republic, the title "Comrade,” Tongzhĭ, is used in place of the titles Xiānsheng, Tàitai, and Xiaojie. Mă Mínglĭ would be

Ma Tongzhì Mă Mínglĭ Tongzhì

The title "Comrade" is applied to all, regardless of sex or marital status. A married* woman does not take her husband18 name in any sense. MS Mínglĭ1 s wife would be

Fang Tóngzhì Fang Baolăn Tongzhì

Children may ì>e given either the mother1 s or the father fs surname at birth. In soxoe families one child has the fatherfs sumaiae, and another child has the mother's surname• Mă MÍnglĭfs and Fang BSolăn9s grown daughter could be

MS Tŏngzhì Má Dĕfēn Tóngzhì

Their grown son could be

Fang Tongzhĭ

Fang Zìqiăng Tŏngzhì

Both in the PRC and elsewhere, of course, there are official titles and titles of respect in addition to the connnon titles ve have discussed here* Several of these will be introduced .later in the course.

The question of adapting foreign nameB to Chinese calls for special consideration. In the People1s Republic the policy is to assign. Chinese phonetic equivalents to foreign names. These approximations are often not as close phonetically as they might "be, since the choice of appropriate written characters may ì>ring in nonphonetic considerations. (An attempt is usually maáe when transliterating to use characters with attractive meanings•) For the most part9 the resulting names do not at all resemble Chinese names. For example, the official version of ”David Andersonis Dàiwĕi Āndĕsēn.

An older approach, still in use outside the PRC, is to construct a valid Chinese name that suggests the foreign name phonetically. For exaxsple 9 ”David Anderson" might be An Dàwèi.

Sometimes, when a foreign surname has the same meaning as a Chinese surname, semantic suggestiveness is chosen over phonetic suggestiveness.

For example, Wang, a common Chinese surname, means "king,,f so "Daniel King” might be rendered Wang Dănìăn.

Students in this course will *be given "both the official PRC phonetic equivalents of their names and Chinese-style names.

The Orientation Module and associated resource modules provide the linguistic tools needed to begin the study of Chinese, The materials also introduce the teaching procedures used in this course.

The Orientation Module is not a typical course module in several respects* First, it does not have a situational topic of its own, but rather leads into the situational topic of the following module—Biographic Information. Second, it teaches only a little Chinese grammar and vocabulary. Third, two of the associated resource modules (Pronunciation and Romeuiiza-tion, Numbers) are not optional; together with the Orientation Module, they are prerequisite to the rest of the course•

Upon successful completion of this module and the two associated resource modules, the student should

1. Distinguish the sounds and tones of Chinese well enough to he able to write the Hănyŭ Pĭnyĭn romanization for a syllable after hearing the syllable.

2. Be able to pronounce any combination of sounds found in the words of the Target Lists vhen given a romanized syllable to read. (Although the entire sound system of Chinese is introduced in the module, the student is responsible for producing only sounds used in the Target Sentences for ORN. Producing the remaining sounds is included in the Objectives for Biographic Information,)

3. Khov the names and locations of five cities and five provinces of China veil enough to point out their locations on a map, and pronounce the names well enough to be understood by a Chinese.

U. Comprehend the numbers 1 through 99 veil enough to write them dovn when dictated, and be able to say them in Chinese when given English equivalents•

5. Understand the Chinese system of using personal names, including the use of titles equivalent to "Mr.,”Mrs.,” "Miss,” and "Comrade."

6. Be able to ask and understand questions about where someone is from.

了. Be able to ask and understand questions about where someone is.

8. Be able to give the English equivalents for all the Chinese expressions in the Target Lists.

9- Be able to say all the Chinese expressions in the Target Lists when cued with English equivalents.*

10. Be able to take part in short Chinese conversations, based on the Target Lists, about how he is, who he is, and where he is from.

TAPES FOR ORN AND ASSOCIATED RESOURCE MODULES

|

Orientat i on (ORN) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pronvinciation aná Romanization (P&R)

P&R 1 P&R 2 P&R 3 P&R U P&R 5 P&R 6 Nuníbers (NUM)

NUM 1 NUM 2 NUM 3 NUM h

Classroom Expressions (CE)

CE 1

IT

|

L. |

A: |

Nĭ shi shĕi? |

Who are you? | |

|

B: |

W5 shi Vang Dànián. |

I am Wang Dànián (Daniel King). | ||

|

A: |

W5 shi Hŭ Mĕilíng. |

I am Hu Mailing. | ||

|

. |

2. |

A: |

Nĭ xìng shenme? |

What is. your surname? |

|

B: |

W5 xìng Wang. |

My surname is Wang (King). | ||

|

A: |

W5 xìng Hu. |

My surname is Hú. | ||

|

3. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he/she? | |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ. |

He is Ma Mínglí. | ||

|

A: |

Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. Ma. | ||

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Ma. | ||

|

A: |

Tā shi Ma Xiăoji?- |

She is Miss Mă. | ||

|

B: |

Tā shi MS TSngzhì• |

He/she is Comrade Ma. | ||

|

h. |

A: |

Wang Xiānsheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wang, who is he? | |

|

B: |

Tā shi Ma Mínglĭ Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. Ma MÍnglĭ. | ||

|

5. |

A: |

Xiānsheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Sir, vho is she? | |

|

B: |

Tā shi Ma Mínglĭ Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Ma Mínglĭ. | ||

|

6. |

A: |

Tŏngzhĭ, ta shi shĕi? |

Comrade, who is she? | |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fang Bad an Tongzhì. |

She is Comrade Fang Băolán. | ||

|

1. |

A: |

Nĭ shi V^Lng Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Wang? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Wang Dànián. |

I am Wang Dàniăn. | |

|

A: |

Wo ì>ŭ shi Wang Xiānsheng. |

I'm not Mr. Wang. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Nĭ xìng Wăng ma? |

Is your surname Wang? |

|

B: |

Wo xìng Wang. |

My surname is Wang, | |

|

A: |

Wo bŭ xìng Wang. |

My surname isn't Wang, |

|

3. |

A: |

NÍn guìxìng? |

Your surname? (POLITE) |

|

B: |

Wo xìng Wang. |

My surname is Vang. | |

|

U. |

A: |

Nĭ Jiào shĕnme? |

What is your given name? |

|

B: |

Wo Jiào Danìăn. |

My given name is Dànìăn (Daniel) | |

|

5. |

A: |

Nĭ hăo a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

Wo hăo. Nĭ ne? |

Ifm fine. And you? | |

|

A: |

Hăo. Xièxie. |

Fine, thank you. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-l tapes)

6. míngzi given name

|

1. |

A: |

Nĭ shi MSiguo rĕn ma? |

Are you an American? |

|

B: |

Shì. |

Yes (I am). | |

|

B: |

Bú shi. |

No (I,m not). | |

|

2. |

A: |

Nĭ shi Zhōngguo rĕn ma? |

Are you Chinese? |

|

B: |

Shì, wS shi Zhōngguo rĕn. |

Yes, Ifm Chinese. | |

|

B: |

Bú shi, wo bú shi Zhōngguo rĕn. |

No, Ifm not Chinese. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Nĭ shi nSiguo rĕn? |

What fs your nationality? |

|

B: |

WS shi MSiguo rĕn. |

I'm an American* | |

|

B: |

W5 shi Zhōngguo rĕn. |

I'm Chinese. | |

|

B: |

W5 shi Yĭngguo rĕn. |

I,m English. | |

|

k. |

A: |

Nĭ shi nărde rĕn? |

Where are you from? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Jiāzhōu rĕn. |

Ifm a Californian. | |

|

B: |

Wo shi Shanghai rĕn. |

from Shanghai. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-l tapes)

|

5. |

Dĕguo |

Germany |

|

6. |

Eguo (Eguo) |

Russia |

|

7. |

Fàjguo (Făguo) |

France |

|

8. |

Rìb?n |

Japan |

|

1. |

A: |

Ándĕsĕn Xiānsheng, nĭ shi nărde rĕn? |

Where are you from, Mr. Anderson? |

|

B; |

Wo shi Dĕzhōu rén. |

I'm from Texas. | |

|

A: |

Ăndĕsēn Fūren ne? |

And Mrs. Anderson? | |

|

B: |

Tā yĕ shi Dĕzhōu rén. |

She is from Texas too. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Tā shi YIngguo rĕn ma? |

Is he English? |

|

B: |

Bŭ shi, tā bŭ shi Yĭngguo rln. |

No, he is not English. | |

|

A: |

Tā àiren ne? |

And his vife? | |

|

B: |

Tā yĕ bú shi YIngguo rĕn. |

She isnTt English either. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Qĭngwèn, nĭ lăojiā zài năr? |

May I ask, where is your family from? |

|

B: |

WS lăojia zài Shandong. |

My family is from Shandong- | |

|

b. |

A: |

Qĭngdao zài zhèr ma? |

Is Qĭngdăo here? (pointing to a map) |

|

B: |

Qĭngdăo bú zài nàr, zài zhèr. |

Qĭngdăo isn’t there; it’s Y.eve. ■ (pointing to a nap; | |

|

5. |

A: B: |

Nĭ àiren xiànzài zài năr? Tā xiànzài zài Jiānádà, |

Where is your spouse now? He/she is in Canada nov. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-l tapes)

6. Learn the pronunciation and .location of any five cities and five provinces of China found on the maps on pages 90-8l.

On a Bĕijĭng street (courtesy of Pat Fox)

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Questions and answers about full names and surnames.

2. Titles and terms of address ("Mr.,” etc.).

Preredulsites to the Unit

(Be sure to complete these "before starting the unit.)

1• Background Notes•

2. P&R 1 (Tape 1 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization),

the tones.

3. P&R 2 (Tape 2 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization),

the tones.

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-l tapes9 the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The drill tape (lD-l)*

About the C-l and P-l Tapes

The C-l and P-l tapes are your introduction to the Chinese words and structures presented in each unit. The tapes give you explanations and practice on the nev material. By the time you have worked through these two tapes, you will be competent in understanding and producing the expressions introduced in the unit.

With the C-l tape, you learn to understand the new vords and structures. The material is presented in short conversational exchanges, first with English translations and later with pauses which allow you to translate. Try to give a complete English translation for each Chinese expression. Your goal when using the C-l tape is to learn the meanings of all the words and structures as they are used in the sentences.

With the P-l tape, you learn to put together these sentences. You learn to pronounce each nev word and use each new structure. When the recorded instructions direct you to pronounce a word or say a sentence, do so out loud. It is important fo矿 you to hear yourself speaking Chinese, so that you vill know whether you are pronouncing the vords correctly. Making the effort to say the expression is a big part of learning it •

It is one thing to think aTxmt how a sentence should be put together or how it should sound. It is another thing to put it together that way or make it sound that way. Your goal when using the P-l tape is to produce the Target List expressions in Chinese when given English equivalents.

At the end of each P-l tape is a review of the Target List which you can go over until you have mastered the expressions.

At times, you may feel that the material on a tape is 'being presented too fast. You may find that there is not enough time allowed for vorking out the meaning of a sentence or saying a sentence the way you want to.

When this happens, stop the tape. If you want to, rewind; Use the control buttons on your machine to make the tape manageable for you most out of it.

and to get the

About the Reference List and the Reference Notes

The Reference List and the Reference Notes are designed to be used before, during, or directly after vork with the C-l and P-l tapes•

The Reference List is a summary of the C-l and P-l tapes. It contains all sentences vhich introduce new material, shoving you both the Chinese sentences written in romanization and their English equivalents. You will find that the list is printed so that either the Chinese or the English can *be covered to allow you to test yourself on comprehension9 production, or romanization of the sentences*

The Reference Notes give you information about grammar, pronunciation, and cultural usage. Some of these explanations duplicate vhat you hear on the C-l and P-l tapes• Other explanations contain nev information.

You may use the Reference List and Reference Notes in various vays.

For example, you may follow the Reference Notes as you listen to a tape, glancing at an exchange or stopping to read a comment whenever you want to. Or you may look through the Reference Notes before listening to a tape, and then use the Reference List while you listen, to help you keep track of where you are. Whichever way you decide to use these parts of a unit, remember that they are reference materials. Don't rely on the translations and romanizations as subtitles for the C-l tape or as cue cards for the P-l tape, for this would rob you of your chance to develop listening and responding skills.

About the Drills

The drills help you develop fluency, ease of response, and confidence. You can go through the drills on your own, vith the drill tapes, and the teacher may take you through them in class as well.

Allow more than half an hour for a half-hour drill tape, since you will usually need to go over all or parts of the tape more than once to get full benefit from it.

The drills include many personal names, providing you vith valuable pronunciation practice. However, if you find the names more than you can handle the first time through the tape, replace them vith the pronoun ta whenever possible• Similar substitutions are often possible with place names.

Some of the drills involve sentences which you may find too long to understand or produce on your first try, and you will need to rewind for another try. Often, particularly the first time through a tape, you vill find the pauses too short, and you will need to stop the tape to give yourself more time. The performance you should aim for with these tapes, however, is full comprehension and full, fluent, and accurate production vhile the tape rolls.

The five basic types of drills are described below.

Substitution Drills: The teacher (T) gives a pattern sentence which the student (S) repeats• Then the teacher gives a word or phrase (a cue) which the student substitutes appropriately in the original sentence.

The teacher follows immediately with a new cue.

Here is an English example of a substitution drill:

T: Are you an American?

S: Are you an American?

T: (cue) English

S: Are you English?

T: (cue) French S: Are you French?

Transformation Drills: On the basis of a model provided at the beginning of the drill, the student makes a certain change in each sentence the teacher says.

Here is an English example of a transformation drill, in which the student is changing affirmative sentences into negative ones: '

T: Ifm going to the bank.

S: I?m not going to the bank.

T: Ifm going to the store.

S: I*m not going to the store,

The student adds something to a pattern sentence as cued

Expansion Drills: by the teacher.

■beginning of the the teacher as cued

of a model given at the questions or remarks by

Response Drills: On the basis drill, the student responds to by the teacher.

|

Here is an English example of a response drill: | ||||||||

|

|

Here is an English example of an expansion drill: | ||||||||||||

|

Combination Drills: On the basis of a model given at the 'beginning of the drill, the student combines two phrases or sentences given "by the teacher into a single utterance.

Here is an English exaiople of a com'bination drill:

|

T: |

I am reading a *book. John gave me the *book. |

|

S: |

I am reading a book which John gave me. |

|

T: |

Mary "bought a picture. I like the picture. |

|

S: |

Mary "bought a picture which I like. |

|

1. |

A: |

NI shi shĕi? |

Who are you? |

|

6: |

W8 shi Wăng Dăniăn. |

I am Vang Daniăn. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Nĭ shi shĕi? |

Who are you? |

|

B: |

W3 shi Hŭ MSilíng. |

I am Hu Mellíng. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ. |

He is Ma Mínglĭ. | |

|

U. |

A: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ. |

He is Ma MÍnglĭ. |

|

B: |

Tā shi Hŭ MSilíng. |

She is Hu Meilíng. | |

|

5- |

A: |

Nĭ xìng shĕnme? |

What is your surname? |

|

B: |

W5 xĭng Wăng. |

My* surname Is Wang. | |

|

6, |

A: |

Tā xĭng 8hénme? |

What is his surname? |

|

7. |

B: A: B: |

Tā xĭng Ma. Tā shi shĕi? Tā shi MS Xìānsheng. |

His surname is ì&. Who is he? He is Mr. Ma« |

|

8. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi V& Mínglĭ Xìānsheng. |

He is Mr, Ma Mínglĭ。 | |

|

9. |

A: |

Wang Xiānsheng, tā shi sheì? |

Mr. Wăng, vho is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi M§ Mínglĭ Xiánsheng. |

He is Mr. Ma Mínglí. | |

|

10. |

A: |

Xiānsheng, tā shi shĕì? |

Sir, who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Xìansheng. |

He is Mr. Ma. | |

|

11. |

A: |

Xiănsheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Sir, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Tàitai. |

She is Mrs。 Ma« | |

|

12. |

A: |

V^big Xiānsheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wáng, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Mă Mínglĭ. | |

|

13. |

A: |

Wang Xìānsheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wang, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Xiaojie. |

She is Miss Ma. | |

|

lh. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Mínglĭ Tongzhì. |

He is Comrade Mă Mínglĭ. |

|

15. |

A: |

Tongzhĭ, tā shi shĕi? |

Comrade, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fang BSolán. |

She is Fang Baolán. | |

|

16. |

A: |

Tongzhì, tā shi shĕi? |

Comrade, vho is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fang Baolăn Tongzhì. |

She is Comrade Fang BSolăn. |

VOCABULARY

|

nĭ |

you |

|

shĕi |

who |

|

8hĕnme |

vhat |

|

shĭ |

to be |

|

tă |

he, she |

|

tàitai |

Mrs. |

|

t6ngzhì |

Comrade |

|

v5 |

I |

|

xiansheng |

Mr.; sir |

|

xiSoJìS (xiaojie) |

Miss |

|

xìng |

to be surnamed |

|

1. |

A: |

Nĭ shi shĕi? |

Who are you? |

|

B: |

WS shi Wăng Dăniăn. |

I am V^ng Dàniăn. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Hĭ shi shĕi? |

Who are you? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Hú Mĕilíng. |

I am Hú Mailing. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ. |

He is Ma Mínglĭ. | |

|

k. |

A: |

Tā shi MS. Minglĭ • |

He is M8. Mínglĭ. |

|

B: |

Tā shi Hú Mĕilíng. |

She is Hú Meilíng. |

Notes on Nos. 1-U

The verb shĭ means "to befl in the sense of Mto be someone or something," as in MI am Daniel King•” It expresses identity. (In Unit k you vill learn a verb which means ”to be” in another sense, ífto "be somewhere," as in ”1 am in Bĕijĭng.11 That verb expresses location.) The vert shĭ is in fche Neutral tone (with no accent mark) except when emphasized.

Unlike verbs in European languages, Chinese verbs do not distinguish first, second, and third persons. A single form serves for all three persons.

|

W5 |

shi |

Wang Dàniăn. |

(I am Wang Dànián.) |

|

Nĭ |

shi |

Hu MSilíng. |

(You are Hu Mĕilíng.) |

|

Tā |

shi |

Ma MÍnglĭ. |

(He is Mă Mínglĭ.) |

Later you will find that Chinese verbs do not distinguish singular and plural, either, and that they dò not distinguish past, present, and future as such. You need to learn only one form for each ver*b.

The pronoun tā is equivalent to both "hen and "she."

The question Nĭ shi shĕi? is actually too direct for most situations, although it is all right from teacher to student or from student to student . (A more polite question is introduced in Unit 2.)

Unlike English, Chinese uses the same word order in questions as in statements.

|

Tā |

shi |

shĕi? |

(Who is he?) |

|

Tā |

shi |

Ma MínKlĭ? |

(He is Ma MínKlĭ.) |

When you answer a question containing a question vord like shéi. "vho,1 simply replace the question word with the information it asks for.

|

.A: |

NX xĭng shĕnme? |

What is your surname? |

|

B: |

Wo xìng Wàng. |

My surname is Wang. |

|

.A: |

Tā xĭng shĕnme? |

What is his surname? |

|

B: |

Tā xìng 成. |

His surname is Ma. |

Jtotes on Nos. 5»6

Xing is a verb, ”to be surnamed.ff It is in the seune position in the sentence as shi, ,fto be.11

|

yfís |

shi |

Wăng Dăniăn. |

|

(i |

am |

W£ng'Dùxián.) |

|

WS |

xìng |

Wang. |

|

(I |

am surnamed |

Wíŭig.) |

|

Notice that the question word shénme • flwhat,11 takes the same position as the question word sh|i_, "vho •” | ||||||

|

|

Nĭ |

xìng |

shĕnme? |

|

(You |

are surnamed |

vhat?) |

Shĕnme is the official spelling. However, the word is pronounced as if it were spelled shàma, or even shĕma (often with a single rise in pitch extending over "both syllablesT~Before another word which begins with a consonant sound, it is usually pronounced as if it vere spelled shem.

|

.A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Xiansheng. |

He is Mr. Ma. |

|

.A: |

Tā shi 8hĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglĭ Xiansheng. |

He is Mr. Ma MÍnglĭ. |

Notes on Hoa, T-8

After the vert shi you may have the full name alone, the surname plus title, or the full name plus title.

|

Tā |

shi |

Ma |

Mínglĭ. | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Ma |

Xiansheng. | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Ma |

Mínglĭ |

Xiansheng. |

Xiansheng, literally ’’first-born,*1 has more of a connotation of respectfulness than ”Mr, Xiansheng is usually applied only to people other than oneself. Do not use the title Xiansheng (or any other respectful title, such as Jiàoshòu, "Professor” when giving your own naaie. If you want to say ,TI am Mr. Jones,” you may say W5 xìng Jones.

|

When a name and title name which gets the heavy the title pronounced with are said together, logically enough it is the stress: WANG Xiansheng, You will often hear oget rANG no full tones: WĀNG Xiansheng. |

|

9. |

A: |

Wang Xiansheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wang, who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Mínglĭ Xiansheng. |

He is Mr. Mă Mínglĭ. | |

|

10. |

A: |

Xiansheng, tā shi shei? |

Sir, who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Ma Xiansheng. |

He is Mr. Ma. |

|

11. A: |

Xiansheng,* tā shi shĕi? |

Sir, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mă Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Ma. |

|

12. A: |

Wang Xiansheng, tā shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wang, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Ma Mínglĭ Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. MS Mínglĭ |

Note on Nos, 9*12

|

When you address someone directly, or the title alone. Xiansheng must be |

use either the name plus the title translated as "sir11 when it is used |

alone, since "Mr.” would not capture its respectful tone. (Tàitai,

alone. You shòuld address Mrs.成

however, is less respectful when used as MăTkitai.)

|

13. |

A: |

痛ng Xiansheng, ta shi shĕi? |

Mr. Wang, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS XiSojiS. |

She is Miss MS. | |

|

Ik. |

A: |

Tā shi shĕi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Ma Btínglĭ Téngzhì. |

He is Comrade Ma MÍnglĭ. | |

|

15. |

A: |

Tongzhì, tā shi shĕi? |

Comrade 9 vho is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fang Báolăn. |

She is Fang Băolăn. | |

|

16. |

A: |

Tongzhì, tā shi shéi? |

Comrade, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fang BSolăn Tŏngzhĭ. |

She is Comrade Fang ^Lolan. |

Note on Nos* 13-16

See the Background Notes on Chinese Personal Ncunes and Titles for Tĕngzhì• "Comrade," and the use of maiden names.

DRILLS

|

A. |

Substitution Drill | |

|

1. |

Speaker: MS Mínglĭ |

You: Tā shi Ma Mínglĭ. (He is Ma MÍnglĭ.) |

|

2. |

Hŭ MSilíng |

Tā shi Hŭ Mĕilíng. (She is Hu Meilíng*) |

|

3. |

Wăng Dăniăn |

Tă shi Wang Dăniăn* (He is Wang Danian *) |

|

h. |

Lĭ Shìxnĭn |

Tā shi Lĭ Shĭmín. (He is Lĭ Shìmín.) |

|

5. |

Liŭ. Lĭrong |

Tā shi Liu Lìrong. (She is Liu Lĭrong.) |

|

6. |

Zhang BSolăn. |

Tā shi Zhang Baolán• (She is Zhăng Baolán*) |

Response Drill

When the When the cue

cue is given by a male speaker, male students should respond, is given by a female speaker, female students should respond.

|

1_ |

Speaker: Nĭ shi shĕi? (cue) Wang Dànìăn (Who are you?) |

You: Wo shi Wang Dàniăn. (I am Wang Daniăii.) |

|

OR Nĭ shi shĕi? (cue) Hú MSilíng (Who are you?) |

¥6 shi Hu Mĕilíng. (I am Hú Mĕilíng.) | |

|

2. |

Nĭ shi shĕi? Liŭ Shìmín (Who are you?) |

Wo shi Liu Shìmín a (I am Liu Shìmín-) |

|

3. |

Nĭ shi shĕi? Chen Huĭrăn (Who are you?) |

Wo shi Chen Huìrăn. (I am Chen Huìrán.) |

|

k. |

Nĭ shi shĕi? Huang Dĕxián (Who are you?) |

Wŏ shi Huáng Dĕxián. (I am Huang Dĕxián.) |

|

5. |

Nĭ shi shei? Zhào Wănrŭ (Who are you?) |

Wo shi Zhào Wănrú. (I am Zhào Wănrú.) |

|

6. |

Nĭ shi shĕi? |

Jiang Bĭngyíng |

Wo shi Jiang Bīngyíng. |

|

(Who are you?) |

(I am Jiang Bĭngyíng.) | ||

|

7. |

Nĭ shi shĕi? |

Gāo YSngpíng |

WS shi Gāo Yongpíng. |

|

(Who are you?) |

(I am Gao Yongpíng.) |

|

C. Response Drill | ||||||||||||||

|

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Questions and answers about given names.

2• Yes/no questions.

3• Negative statements•

U. Greetings.

Prerequisites to the Unit

1. P&R 3 and P&R h (Tapes 3 and k of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization).

Materials You Vill Need

1. The C-l and P-l tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The 2D-1 tape.

|

1- |

A: |

Tā shi Wang Tàitai ma? |

Is she Mrs. Wang? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Wang Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Wang. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Nĭ shi Wang Xiansheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Wang? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Wang Dànián. |

I am Wang Dànián. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Nĭ shi Mă Xiansheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Ma? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Wang Dàniăn* |

I am Wang Dànián. | |

|

k. |

A: |

lií shi Mă Xiansheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Ma? |

|

B: |

WS ì)ú shi MS Xiansheng. |

Ifm not Mr. Ma. | |

|

5. |

A: |

W5 shi l^ng Dàniăn* |

I asi Wang Danián. |

|

B: |

WS ì?ú shi Wang Dănián. |

Ifzn not Wáng Dánìán. | |

|

6. |

A: |

Nĭ xĭng Fāng ma? |

Is your surname Fang? |

|

B: |

WS tŭ xìng Fang. |

ìty surname isn't Fang. | |

|

了. |

A: |

W5 xìng Wăng. |

Ify surname is Wang. |

|

B: |

W5 *bŭ xìng ^Lng. |

My surname isn't ^íxig. | |

|

8. |

A: |

Nĭ xĭng M§ ma? |

Is your surname Ma? |

|

B: |

Bú xĭng MS. Xing Wăng. |

My surname isn't Ma. Itfs Wang. | |

|

9. |

A: |

Nín guìxĭng? |

Your surname? (POLITE) |

|

B: |

W5 xìng Wang. |

My surname is Wáng. | |

|

10. |

A: |

Nĭ jiào shĕnme? |

What is your given name? |

|

B: |

WS Jìào Dànìán. |

MSy given name is Dàniăn. | |

|

11. |

A: |

Nĭ hao a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

W5 hSo. |

Ifm fine. | |

|

12. |

A: |

Nĭ hao a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

W5 hSo. Nl ne? |

I1* fine. And you? | |

|

A: |

HSo, xièxìe. |

Fine, thanks. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-l tapes)

|

13. |

míngzi |

given name |

VOCABULARY

|

a |

(question marker) |

|

*bù/bú |

not |

|

bú shi |

not to be |

|

guìxĭng |

(honorable) surname |

|

hSo |

to te fine, to \>e well |

|

Jiào |

to ì>e called |

|

ma |

(question marker) |

|

míngzi |

given name |

|

ne |

(question marker) |

|

xiĕxie |

thank you |

|

1. |

A: B: |

Tā shi Wang Tàitai ma? Tā shi Wang Tàitai. |

Is she Mrs. Wang? She is Mrs. Wang. |

|

2. |

A: B: |

Nĭ shi Wang Xiansheng ma? W5 shi Wang Dàniăn. |

Are you Mr. Wang? I am Wang Dăniăn. |

|

3- |

A: B: |

Nĭ shi Ma Xiansheng ma? Wo shi Wăng Dàniăn. |

Are you Mr. Ma? I am Wang Dănìăn. |

Notes rn Nos. 1-3

r.he marker ma may be added to any statement to turn it into a question which may be answered "yes" or "no,"

|

Tá |

shi |

Wang Tàitai. |

(She is Mrs. Wang.) | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Vang Tàitai |

ma? |

(Is she Mrs. Wáng?) |

The reply to a yes/no question is commonly a complete affirmative or negative statement, although, as you vill see later, the statement may "be stripped dovn considerably.

|

1*. A: |

Nĭ shi Mă Xiansheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Ma? |

|

B: |

WS *bŭ shi Mă Xiănsheng. |

I’m not Mr. Ma. |

|

5. A: |

WS shi Wang Dàniăn. |

I am Wang Dàniăn. |

|

B: |

Wo bŭ shi Wang Dàniăn. |

I’m not ^ng Dàniăn. |

Notes on Nos. U»5

The negative of the verb shi, "to "be,” is bn shi, "not to "be." The equivalent of "not” is the syllable bù. The tone for the syllable bŭ depends on the tone of the following"syllal)le. When folloved *by a syllable with a High, Rising, or Low tone, a Falling tone is used (bù). When followed *by a syllable with a Falling or Neutral tone, a Rising tone is used (bŭ).

|

bŭ |

fēì |

(not |

to |

fly) |

|

bŭ |

fĕi |

(not |

to |

be fat) |

|

"bŭ |

fĕi |

(not |

to |

slander) |

|

*bú |

fèi |

(not |

to |

waste) |

Almost all of the first fev verbs you learn happen to be in the Falling tone, and so take tŭ. But remember that tù is the basic form. That is the form the syllable takes when it stands alone as a short "no,f answer一Bù and vhen it is discussed, as in yTBu means fnot *.ff

Notice that even though shi, "to be,M is usually pronounced in the Neutral tone in the phrase bu shi, the original Falling tone of shi still causes *bù to "be pronounced vith a Rising tone: bŭ.

|

W3 |

shi |

Wang Dănián. | ||

|

(I |

an |

Wang Dàniăn.) |

|

bŭ |

shi |

MS Xiansheng« | ||

|

(I |

am |

not |

Mr. Ma.) |

|

6. |

A: |

NX xĭng Fang ma? |

Is your surname Fang? |

|

B: |

WS bŭ xĭng Fang. |

My surname isn’t Fang. | |

|

7. |

A: |

W8 xing Wăng. |

Ify surname is Wang. |

|

B: |

WS bŭ xìng Wang. |

Ify surname isnft Wang. | |

|

8. |

A: |

Nĭ xìng MS zna? |

Is your surname Ma? |

|

B: |

Bŭ xĭng MS. Xing Wang. |

My surname isnft Ma, It,s Wang« |

Note on No* 8

It is quite common in Chinese--much commoner than in English--to omit the subject of a sentence vhen it is clear from the context.

|

A: |

Nín guìxìng? |

Your surname? (POLITE) |

|

B: |

Wo xĭng Wang. |

My surname is Wáng. |

Notes on No. 9

Nín is the polite equivalent of nĭ, "you.1,

Guìxĭng is a polite noun, "sùrname." Guì means "honorable." Xìng^ vhich you have learned as the vert ”to "be surnalned,,, is in this case a noun, ,’surnaiDe•"

Literally, Nín guìxíng? is "Your surname?" The implied question is understood, and the sentenceM consists of the subject alone.

10. A: Nĭ Jiào shĕnme? What is your given name?

B: Wo jiào Dànián. My given name is Dànián.

Note on No* 10

Jiào is a verb meaning "to be called. In a discussion of personal names, we can say that it means "to be given-named,M

|

11. |

A: |

Nĭ hao a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

WS hSo. |

I’m fine. |

Notes on No. 11

Notice that the Low tones of wo and nĭ change to Rising tones before the Low tone of hao: Ni hao a? hao.

Hao is a verb—”to "be good,” "to be veil,” "to be fine.” Since it functions like the verb "to "be” plus an adjective in English, ve will call it an adjectival verb.

|

WS |

hao. |

|

(I |

am fine•) |

|

Nĭ |

hao |

a? |

|

(You |

are fine |

|

12. |

A: |

Nĭ hăo a? |

Hov are you? |

|

B: |

W5 hSo. Nĭ ne? |

Ifm fine. And you? | |

|

A: |

HSo, xièxie. |

Fine, thanks. |

Notes on No. 12

The marker ne makes a question out of the single vord ill, "you*’: "And you?” or "Hov about you?11

Xié is the verb "to thank •” "I thank you11 would be W5 xièxie nĭ. Xléxie is often repeated: Xiĕxle^ xièxie.

|

13. mĭngzi |

given name |

Note on No. 13

One way to ask what someone's given name is: Nĭ jiăo shĕnme mingzi?

|

A. Transformation Drill | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

B. Response Drill | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

C. Response Drill

All of your answers vill "be negative. Give the correct name according to the cue.

|

1. |

Speaker: Tā shi Wang Xiansheng ma? (cue) Liu (Is he Mr. ^īangĭ) |

You: Bú shi. Tā shi Liú Xiansheng. (No. He is Mr. Liú,) |

|

2, |

Tā shi Gāo Xi&ojiS ma? Zhăo (Is she Miss Gao?) |

Bŭ shi. Tā shi Zhào Xiăojiĕ, (No. She is Miss Zhào.) |

|

3. |

Ta shi Huăng Téngzhì ma? Wing (Is she Comrade Huang?) |

Bŭ shi. Tā shi Wăng Tŏngzhí. (No. She is Comrade Vang*) |

|

k. |

Tā shi Y&ng Tàitai ma? JiSng (Is she Mrs. Yang?) |

Bu shi. Ta shi Jiang Tăltai. (No. She is Mrs. Jiang.) |

|

5. |

Tā shi MS Xiansheng ma? Mao (Is he Mr. Ma?) |

Bŭ shi, Tā shi Mao Xiansheng. (No. He is Mr.戚o.) |

|

6. |

Tā shi Zhou XlSojiS ma? Zhào (Is she Miss Zhou?) |

Bú shi. Tă shi Zhào Xiăojig. (No. She is Miss Zhào.) |

|

7. |

Tā shi Jiang Xiansheng ma? JiSng (Is he Mr. Jiang?) |

Bŭ shi, Tā shi JiSng Xiansheng. (No. He is Mr. Jiang.) |

Response Drill

This drill is a combination of the two previous drills. Give an affirmative or a negative ansver according to the cue.

|

1. |

Speaker: Tā shi Liŭ Tàitai ma? (cue) Liu (Is she Mrs. Liu?) |

You: Shi. Tā shi Liŭ Tàitai. (Yes* She is Mrs. Liu.) |

|

OR Tă shi Liŭ Tàìtai ma? Huang (Is she Mrs. Liu?) |

Bŭ shi. Tā shi Huang Tàìtaì. (No. She is Mrs. Huang.) | |

|

2. |

Tā shi Wáng Xiansheng ma? Wang (is he Mr. Wang?) |

Shi. Tā shi Wăng Xiāpsheng. (Yes. He is Mr. Wáng.) |

|

3. |

Tā shi Gāo Tàitai ma? Zhào (Is she Mrs. Gāo?) |

Bu shi. Tā shi Zhào Tàitai. (No. She is Mrs. Zhào.) |

|

k. |

Tā shi Tăng Xiaojie ma? Tang (is she Miss Tang?) |

Shi. Ta shi Tang Xiăoji?. (Yes. She is Miss Tang.) |

|

5. |

Tā shi Huang Xiansheng ma? Wang (Is he Mr. Huang?) |

Bŭ shi. Tā shi Wang Xiansheng. (No. He is Mr. Wang^) |

|

6. |

Tā shi Zhang Tàitaì ma? Jiang (Is she Mrs. Zhāng?) |

Bŭ.shi. Tā shi Jlāng Tàitai-(No. She is Mrs. Jiang.) |

|

TransformatIon Drill | ||||||||||||||

|

|

F. Transformation Drill | |||||||||||||||

|

|

6. |

W8 xing Zhăng. |

WS bŭ xing Zhāng. |

|

7. |

W5 xing Zhōu. |

WS bú xing Zhou. |

|

G. Transformation Drill | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

H. Expansion Drill | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

I. Expansion Drill | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

J. Response Drill | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Transformation Drill | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L. Transformation Drill | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Combination Drill | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Nationality.

2. Home state9 province, and city.

Prerecmlsites to the Unit

1. P6R 5 and P&R 6 (Tapes 5 and 6 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization).

2. NUM 1 and NUM 2 (Tapes 1 and 2 of the resource module on Numbers), the numbers from 1 to 10,

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-l tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The C-2 and P-2 tapes, the Workbook.

3. The 3D-1 tape.

|

REFERENCE LIST | |||

|

1. |

A: |

NX shi MSiguo rén ma? |

Are you an American? |

|

B: |

W5 shi MSìguo rĕn. |

Ifm an American. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Ni shi Zbōngguo rĕn ma? |

Are you Chinese? |

|

B: |

W8 shi Zbōngguo rĕn. |

I,m Chinese. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Wang Xiansheng, nĭ shi YIngguo rĕn ma? |

Mr. W&ng, are you English? |

|

B: |

W5 bú shi Yĭngguo rĕn. |

ī^m not English. | |

|

1*. |

A: |

Nĭ shi Zhōngguo rĕn ma? |

Are you Chinese? |

|

B. |

Bú shi. |

No. | |

|

A: |

Nĭ shi MSìguo rĕn ma? |

Are you an American? | |

|

B: |

Shì. |

Yes, I am* | |

|

5. |

A: |

MS. XiSoJìS shi MSiguo rĕn ma? |

Is Miss MS an American? |

|

B: |

Bŭ shi, tā tŭ shi Mgiguo rĕn* |

No, she is not American. | |

|

A: |

Tā shi Zhongguo rĕn xna? |

Is she Chinese? | |

|

B: |

Shi, tā shi Zhōngguo rĕn. |

Yes, she is Chinese. | |

|

6. |

A: |

虹 shi nSiguo rĕn? |

What is your nationality? |

|

B: |

W5 shi MSiguo rén. |

I'm American. | |

|

7. |

A: |

Tā shi nSiguo rĕn? |

What is his nationality? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Yĭngguo rĕn. |

He is English. | |

|

8. |

A: |

Nĭ shi n&rde rén? |

Where are you from? |

|

B: |

WS shi ShănghSi rĕn. |

I'm from ShănghSl. | |

|

9. |

A: |

Tà shi Fang BSolănde xiansheng. |

He is Fang BSòlánfs husband. |

|

10. |

A: |

Tā shi nSrde rĕn? |

Where is he from? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Shandong rĕn. |

He,s from Shandong. | |

|

11. |

A: |

Nĭ shi nSrde rĕn? |

Where are you from? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Jiăzhōu rĕn. |

I,m a Californian. | |

|

12. |

A: NX |

shi MSiguo rĕn ma? |

Are you an American? |