CM 0180 S

A MODULAR APPROACH

STUDENT TEXT

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION

MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

SPONSORED BY AGENCIES OF THE

UNITED STATES AND CANADIAN GOVERNMENTS

This publication is to be used primarily in support of instructing military personnel as part of the Defense Language Program (resident and nonresident). Inquiries concerning the use of materials, including requests for copies, should be addressed to:

Defense Language Institute

Foreign Language Center

NonresidentTraining Division

Presidio of Monterey, CA 93944-5006

Topics in the areas of politics, international relations, mores, etc., which may be considered as controversial from some points of view, are sometimes included in the language instruction for DLIFLC students since military personnel may find themselves in positions where a clear understanding of conversations or written materials of this nature will be essential to their mission. The presence of controversial statements-whether real ōr apparent-in DLIFLC materials should not be construed as representing the opinions of the writers, the DLIFLC, or the Department of Defense.

Actual brand names and businesses are sometimes cited in DLIFLC instructional materials to provide instruction in pronunciations and meanings. The selection of such proprietary terms and names is based solely on their value for instruction in the language. It does not constitute endorsement of any product or commercial enterprise, nor is it intended to invite a comparison with other brand names and businesses not mentioned.

In DLIFLC publications, the words he, him, and/or his denote both masculine and feminine genders. This statement does not apply to translations of foreign language texts.

The DLIFLC may not have full rights to the materials it produces. Purchase by the customer does net constitute authorization for reproduction, resale, or showing for profit. Generally, products distributed by the DLIFLC may be used in any not-for-profit setting without prior approval from the DLIFLC.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach originated in an interagency conference held at the Foreign Service Institute in August 1973 to address the need generally felt in the U.S. Government language training community for improving and updating Chinese materials, to reflect current usage in Beijing and Taipei.

The conference resolved to develop materials which were flexible enough in form and content to meet the requirements of a wide range of government agencies and academic institutions.

A Project Board was established consisting of representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency Language Learning Center, the Defense Language Institute, the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute, the Cryptologic School of the National Security Agency, and the U.S. Office of Education, later Joined by the Canadian Forces Foreign Language School. The representatives have included Arthur T. McNeill, John Hopkins, and John Boag (CIA); Colonel John F. Elder III, Joseph C. Hutchinson, Ivy Gibian, and Major Bernard Muller-Thym (DLI); James R. Frith and John B. Ratliff III (FSI); Kazuo Shitama (NSA); Richard T. Thompson and Julia Petrov (OE); and Lieutenant Colonel George Kozoriz (CFFLS).

The Project Board set up the Chinese Core Curriculum Project in 1971* in space provided at the Foreign Service Institute. Each of the six U.S. and Canadian government agencies provided funds and other assistance.

Gerard P. Kok was appointed project coordinator, and a planning council was formed consisting of Mr. Kok, Frances Li of the Defense Language Institute, Patricia O'Connor of the University of Texas, Earl M. Rickerson of the Language Learning Center, and James Wrenn of Brown University. In the fall of 1977* Lucille A. Barale was appointed deputy project coordinator. David W. Dellinger of the Language Learning Center and Charles R. Sheehan of the Foreign Service Institute also served on the planning council and contributed material to the project. The planning council drew up the original overall design for the materials and met regularly to review their development.

Writers for the first half of the materials were John H. T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale, and Roberta S. Barry, who worked in close cooperation with the planning council and with the Chinese staff of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Harvey developed the instructional formats of the comprehension and production self-study materials, and also designed the communication-based classroom activities and wrote the teacher’s guides. Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry wrote the tape scripts and the student text. By 1978 Thomas E. Madden and Susan C. Pola had Joined the staff. Led by Ms. Barale, they have worked as a team to produce the materials subsequent to Module 6.

All Chinese language material was prepared or selected by Chuan 0. Chao, Ying-chi Chen, Hsiao-Jung Chi, Eva Diao, Jan Hu, Tsung-mi Li, and Yunhui C. Yang, assisted for part of the time by Chieh-fang Ou Lee, Ying-ming Chen, and Joseph Yu Hsu Wang. Anna Affholder, Mei-li Chen, and Henry Khuo helped in the preparation of a preliminary corpus of dialogues.

Administrative assistance was provided at various times by Vincent Basciano, Lisa A. Bowden, Jill W. Ellis, Donna Fong, Renee T. C. Liang, Thomas E. Madden, Susan C. Pola, and Kathleen Strype.

The production of tape recordings was directed by Jose M. Ramirez of the Foreign Service Institute Recording Studio. The Chinese script was voiced by Ms. Chao, Ms. Chen, Mr. Chen, Ms. Diao, Ms. Hu, Mr. Khuo, Mr. Li, and Ms. Yang. The English script was read by Ms. Barale, Ms. Barry, Mr. Basciano, Ms. Ellis, Ms. Pola, and Ms. Strype.

The graphics were produced by John McClelland of the Foreign Service Institute Audio-Visual staff, under the general supervision of Joseph A. Sadote, Chief of Audio-Visual.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach was field-tested with the cooperation of Brown University; the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center; the Foreign Service Institute; the Language Learning Center; the United States Air Force Academy; the University of Illinois; and the University of Virginia.

Colonel Samuel L. Stapleton and Colonel Thomas G. Foster, Commandants of the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center, authorized the DLIFLC support necessary for preparation of this edition of the course materials. This support included coordination, graphic arts, editing, typing, proofreading, printing, and materials necessary to carry out these tasks.

James R. Frith, Chairman

Chinese Core Curriculum Project Board

CONTENTS

Introduction Section I: About the Course

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION Objectives ....................... .....

Reference Notes ......... . ......... ..... 28

Full names and surnames Titles and terms of address Drills

Given names

Yes/no questions

Negative statements

Nationality

Home state, province, and city Drills

Location of people and places Where people’s families are from

Appendices

MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION Objectives

Where people are staying (hotels) Short answers The question word něige "which?" Drills............... 105

Where people are staying (houses) Where people are working Addresses The marker de The marker ba The prepositional verb zài Drills..........................120

Members of a family The plural ending -men The question word jl- "how many"

The adverb dōu ’’all"

Several ways to express "and" Drills . . .

Arrival and departure times

The marker le

The shi... de construction Drills

Date and place of birth

Days of the week

Ages

The marker le for new situations Drills

Reference List .... .......... ..........

Reference Notes ................ .......

Duration phrases

The marker le for completion

The "double le" construction

The marker guo

Action verbs

Where someone works

Where and what someone has studied What languages someone can speak Auxiliary verbs General objects

More on duration phrases The marker le for new situations in negative sentences Military titles and branches of service The marker ne Process verbs Drills............................223

INTRODUCTION

This course is designed to give you a practical command of spoken Standard Chinese. You will learn both to understand and to speak it. Although Standard Chinese is one language, there are differences between the particular form it takes in Beijing and the form it takes in the rest of the country. There are also, of course, significant nonlinguistic differences between regions of the country. Reflecting these regional differences, the settings for most conversations are Beijing and Taipei.

This course represents a new approach to the teaching of foreign languages. In many ways it redefines the roles of teacher and student, of classwork and homework, and of text and tape. Here is what you should expect:

The focus is on communicating in Chinese in practical situations—the obvious ones you will encounter upon arriving in China. You will be communicating in Chinese most of the time you are in class. You will not always be talking about real situations, but you will almost always be purposefully exchanging information in Chinese.

This focus on conimunicating means that the teacher is first of all your conversational partner. Anything that forces him1 back into the traditional roles of lecturer and drillmaster limits your opportunity to interact with a speaker of the Chinese language and to experience the language in its full spontaneity, flexibility, and responsiveness.

Using class time for communicating, you will complete other course activities out of class whenever possible. This is what the tapes are for. They introduce the new material of each unit and give you as much additional practice as possible without a conversational partner.

The texts summarize and supplement the tapes, which take you through new material step by step and then give you intensive practice on what you have covered. In this course you will spend almost all your time listening to Chinese and saying things in Chinese, either with the tapes or in class.

How the Course Is Organized

The subtitle of this course, "A Modular Approach,” refers to overall organization of the materials into MODULES which focus on particular situations or language topics and which allow a certain amount of choice as to what is taught and in what order. To highlight equally significant features of the course, the subtitle could just as well have been "A Situational Approach," "A Taped-Input Approach," or "A Communicative Approach."

Ten situational modules form the

ORIENTATION (ORN)

BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION (BIO)

MONEY (MON)

DIRECTIONS (DIR)

TRANSPORTATION (TRN)

ARRANGING A MEETING (MTG)

SOCIETY (SOC)

TRAVELING IN CHINA (TRL)

LIFE IN CHINA (LIC)

TALKING ABOUT THE NEWS (TAN)

Each core module consists of tapes,

core of the course:

Talking about who you are and where you are from.

Talking about your background, family, studies, and occupation and about your visit to China.

Making purchases and changing money.

Asking directions in a city or in a building.

Taking buses, taxis, trains, and planes, including finding out schedule information, buying tickets, and making reservations.

Arranging a business meeting or a social get-together, changing the time of an appointment, and declining an invitation.

Talking about families, relationships between people, cultural roles in traditional society, and cultural trends in modern society.

Making travel arrangements and visiting a kindergarten, the Great Wall, the Ming Tombs, a commune, and a factory.

Talking about daily life in Beijing street committees, leisure activities, traffic and transportation, buying and rationing, housing.

Talking about government and party policy changes described in newspapers: the educational system,-agricultural policy, international policy, ideological policy, and policy in the arts.

student textbook, and a workbook.

In addition to the ten CORE modules, there are also RESOURCE modules and OPTIONAL modules’. Resource modules teach particular systems in the language, such as numbers and dates. As you proceed through a situational core module, you will occasionally take time out to study part of a resource module. (You will begin the first’ three of these while studying the Orientation Module.)

PRONUNCIATION AND ROMANIZATION (P&R) The sound system of Chinese and the Pinyin system of romanization.

NUMBERS (NUM) Numbers up to five digits.

CLASSROOM EXPRESSIONS (CE) Expressions basic to the classroom

learning situation.

TIME AND DATES (T&D) Dates, days of the week, clock time,

parts of the day.

GRAMMAR Aspect and verb types, word order,

multisyllabic verbs and bǎ, auxiliary verbs, complex sentences, adverbial expressions.

Each module consists of tapes and a student textbook.

The eight optional modules focus on particular situations:

RESTAURANT (RST)

HOTEL (HTL)

PERSONAL WELFARE (WLF)

POST OFFICE AND TELEPHONE (PST/TEL)

CAR (CAR)

CUSTOMS SURROUNDING MARRIAGE, BIRTH, AND DEATH (MBD)

NEW YEAR’S CELEBRATION (NYR)

INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS (l&O)

Each module consists of tapes and a student textbook. These optional modules may be used at any time after certain core modules.

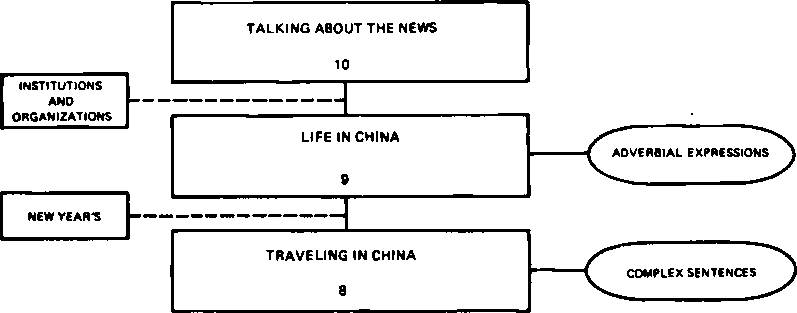

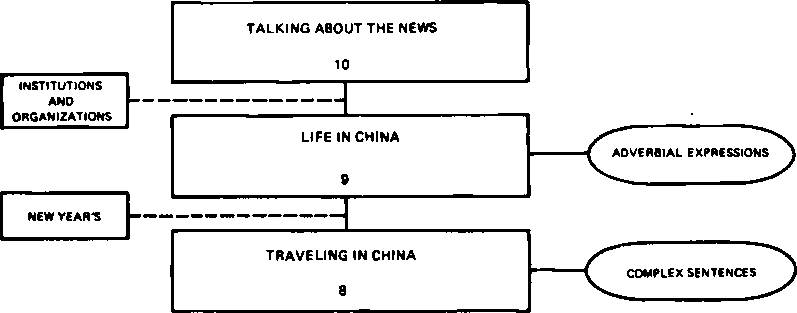

The diagram on page shows how the core modules, optional modules, and resource modules fit together in the course. Resource modules are shown where study should begin. Optional modules are shown where they may be introduced.

STANDARD CHINESE : A MODULAR APPROACH

KEY

Inside a Core Module

Each core module has from four to eight units. A module also includes

Objectives: The module objectives are listed at the beginning of the text for each module. Read these before starting work on the first unit to fix in your mind what you are trying to accomplish and what you will have to do to pass the test at the end of the module.

Target Lists: These follow the objectives in the text. They summarize the language content of each unit in the form of typical questions and answers on the topic of that unit. Each sentence is given both in roman-ized Chinese and in English. Turn to the appropriate Target List before, during, or after your work on a unit, whenever you need to pull together what is in the unit.

Review Tapes (R-l): The Target List sentences are given on these tapes. Except in the short Orientation Module, there are two R-l tapes for each module.

Criterion Test: After studying each module, you will take a Criterion Test to find out which module objectives you have met and which you need to work on before beginning to study another module.

Inside a Unit

Here is what you will be doing in each unit. First, you will work through two tapes:

1. Comprehension Tape 1 (C-l): This tape introduces all the new words and structures in the unit and lets you hear them in the context of short conversational exchanges. It then works them into other short conversations and longer passages for listening practice, and finally reviews them in the Target List sentences. Your goal when using the tape is to understand all the Target List sentences for the unit.

2. Production Tape 1 (P-1): This tape gives you practice in pronouncing the new words and in saying the sentences you learned to understand on the C-l tape. Your goal when using the P-1 tape is to be able to produce any of the Target List sentences in Chinee? when given the English equivalent.

The C-l and P-1 tapes, not accompanied by workbooks, are "portable" in the sense that they do not tie you down to your desk. However, there are some written materials for each unit which you will need to work into your study routine. A text Reference List at the beginning of each unit contains the sentences from the C-l and P-1 tapes. It includes both the Chinese sentences and their English equivalents. The text Reference Notes restate and expand the comments made on the C-l and P-1 tapes concerning grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and culture.

After you have worked with the C-l and P-1 tapes, you go on to two class activities:

3. Target List Review: In this first class activity of the unit, you find out how well you learned the C-l and P-1 sentences. The teacher checks your understanding and production of the Target List sentences. He also presents any additional required vocabulary items, found at the end of the Target List, which were not on the C-l and P-1 tapes.

U. Structural Buildup: During this class activity, you work on your understanding and control of the new structures in the unit. You respond to questions from your teacher about situations illustrated on a chalkboard or explained in other ways.

After these activities, your teacher may want you to spend some time working on the drills for the unit.

5. Drill Tape: This tape takes you through various types of drills based on the Target List sentences and on the additional required vocabulary.

6. Drills: The teacher may have you go over some or all of the drills in class, either to prepare for work with the tape, to review the tape, or to replace it.

Next, you use two more tapes. These tapes will give you as much additional practice as possible outside of class.

7. Comprehension Tape 2 (C-2): This tape provides advanced listening practice with exercises containing long, varied passages which fully exploit the possibilities of the material covered. In the C-2 Workbook you answer questions about the passages.

8. Production Tape 2 (P-2): This tape resembles the Structural Buildup in that you practice using the new structures of the unit in various situations. The P-2 Workbook provides instructions and displays of information for each exercise.

Following work on these two tapes, you take part in two class activities:

9. Exercise Review: The teacher reviews the exercises of the C-2 tape by reading or playing passages from the tape and questioning you on them. He reviews the exercises of the P-2 tape by questioning you on information displays in the P-2 Workbook.

10. Communication Activities: Here you use what you have learned in the unit for the purposeful exchange of information. Both fictitious situations (in Communication Games) and real-world situations involving you and your classmates (in "interviews”) are used.

Materials and Activities for a Unit

TAPED MATERIALS

C-l, P-1 Tapes

WRITTEN MATERIALS

Target List Reference List Reference Notes

D-l Tapes

C-2, P-2 Tapes

Drills

Reference Notes C-2, P-2 Workbooks

CLASS ACTIVITIES

Target List Review

Structural Buildup Drills

Exercise Review

Communication Activities

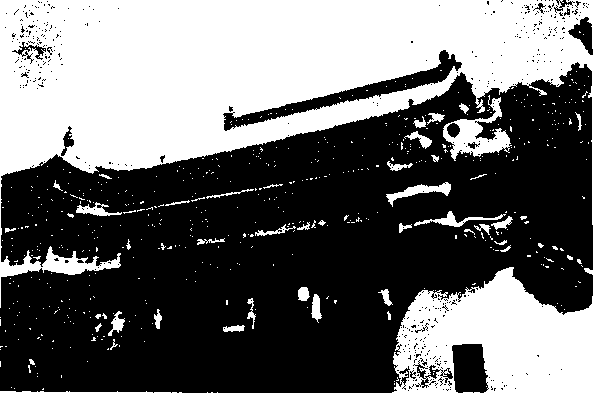

Wen wǔ Temple in central Taiwan (courtesy of Thomas Madden)

The Chinese Languages

We find it perfectly natural to talk about a language called ’’Chinese. ’’ We say, for example, that the people of China speak different dialects of Chinese, and that Confucius wrote in an ancient form of Chinese. On the other hand, we would never think of saying that the people of Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal speak dialects of one language, and that Julius Caesar wrote in an ancient form of that language. But the facts are almost exactly parallel.

Therefore, in terms of what we think of as a language when closer to home, ’’Chinese” is not one language, but a family of languages. The language of Confucius is partway up the trunk of the family tree. Like Latin, it lived on as a literary language long after its death as a spoken language in popular use. The seven modern languages of China, traditionally known as the "dialects," are the branches of the tree. They share as strong a family resemblance as do Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese, and are about as different from one another.

The predominant language of China is now known as Putonghua, or "Standard Chinese" (literally "the common speech"). The more traditional term, still used in Taiwan, is Guoyǔ, or "Mandarin" (literally "the national language"). Standard Chinese is spoken natively by almost two-thirds of the population of China and throughout the greater part of the country.

The term "Standard Chinese" is often used more narrowly to refer to the true national language which is emerging. This language, which is already the language of all national broadcasting, is based primarily on the 'Peking dialect, but takes in elements from other dialects of Standard Chinese and even from other Chinese languages. Like many national languages, it is more widely understood than spoken, and is often spoken with some concessions to local speech, particularly in pronunciation.

The Chinese languages and their dialects differ far more in pronunciation than in grammar and vocabulary. What distinguishes Standard Chinese most from the other Chinese languages, for example, is that it has the fewest tones and the fewest final consonants.

The remaining six Chinese languages, spoken by approximately a quarter of the population of China, are tightly grouped in the southeast, below the Yangtze River. The six are: the Wu group (Wu), which includes the "Shanghai dialect"; Hunanese (Xiāng); the "Kiangsi dialect" (Gan); Cantonese (Yuè), the language of Guangdong, widely spoken in Chinese communities in the United States; Fukienese (Min), a variant of which is spoken by a majority on Taiwan and hence called Taiwanese; and Hakka (Kèjiā). spoken in a belt above the Cantonese area, as well as by a minority on Taiwan. Cantonese, Fukienese, and Hakka are also widely spoken throughout Southeast Asia.

There are minority ethnic groups in China who speak non-Chinese languages. Some of these, such as Tibetan, are distantly related to the Chinese languages. Others, such as Mongolian, are entirely unrelated.

Some Characteristics of Chinese

To us, perhaps the most striking feature of spoken Chinese is the use of variation in tone ("tones") to distinguish the different meanings of syllables which would otherwise sound alike. All languages, and Chinese is no exception, make use of sentence intonation to indicate how whole sentences are to be understood. In English, for example, the rising pattern in "He’s gone?" tells us that the sentence is meant as a question. The Chinese tones, however, are quite a different matter. They belong to individual syllables, not to the sentence as a whole. An inherent part of each Standard Chinese syllable is one of four distinctive tones. The tone does just as much to distinguish the syllable as do the consonants and vowels. For example, the only difference between the verb "to buy," m&i, and the verb "to sell," mài, is the Low tone (w) and the Falling tone (-). And yet these words are just as distinguishable as our words "buy" and "guy," or "buy" and "boy." Apart from the tones, the sound system of Standard Chinese is no more different from English than French is.

Word formation in Standard Chinese is relatively simple. For one thing, there are no conjugations such as are found in many European languages. Chinese verbs have fewer forms than English verbs, and nowhere near as many irregularities. Chinese grammar relies heavily on word order and often the word order is the same as in English. For these reasons Chinese is not as difficult for Americans to learn to speak as one might think.

It is often said that Chinese is a monosyllabic language. This notion contains a good deal of truth. It has been found that, on the average, every other word in ordinary conversation is a single-syllable word. Moreover, although most words in the dictionary have two syllables, and some have more, these words can almost always be broken down into singlesyllable units of meaning, many of which can stand alone as words.

Written Chinese

Most languages with which we are familiar are written with an alphabet. The letters may be different from ours, as in the Greek alphabet, but the principle is the same: one letter for each consonant or vowel sound, more or less. Chinese, however, is written with "characters" which stand for whole syllables—in fact, for whole syllables with particular meanings. Although there are only about thirteen hundred phonetically distitìct syllables in standard Chinese, there are several thousand Chinese characters in everyday use, essentially one for each single-syllable unit of meaning. This means that many words have the same pronunciation but are written with different characters, as tiān, "sky," X, and tiān, "to add," "to increase,"

Chinese characters are often referred to as "ideographs," which suggests that they stand directly for ideas. But this is misleading. It is better to think of them as standing for the meaningful syllables of the spoken language.

Minimal literacy in Chinese calls for knowing about a thousand characters. These thousand characters, in combination, give a reading vocabulary of several thousand words. Full literacy calls for knowing some three thousand characters. In order to reduce the amount of time needed to learn characters, there has been a vast extension in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) of the principle of character simplification, which has reduced the average number of strokes per character by half.

During the past century, various systems have been proposed for representing the sounds of Chinese with letters of the Roman alphabet. One of these romanizations, Hànyǔ Pinyin (literally "Chinese Language Spelling," generally called "Pinyin" in English), has been adopted officially in the PRC, with the short-term goal of teaching all students the Standard Chinese pronunciation of characters. A long-range goal is the use of Pinyin for written communication throughout the country. This is not possible, of course, until speakers across the nation have uniform pronunciations of Standard Chinese. For the time being, characters, which represent meaning, not pronunciation, are still the most widely accepted way of communicating in writing.

Pinyin uses all of the letters in our alphabet except v, and adds the letter u. The spellings of some of the consonant sounds are rather arbitrary from our point of view, but for every consonant sound there is only one letter or one combination of letters, and vice versa. You will find that each vowel letter can stand for different vowel sounds, depending on what letters precede or follow it in the syllable. The four tones are indicated by accent marks over the vowels, and the Neutral tone by the absence of an accent mark:

One reason often given for the retention of characters is that they can be read, with the local pronunciation, by speakers of all the Chinese languages. Probably a stronger reason for retaining them is that the characters help keep alive distinctions of meaning between words, and connections of meaning between words, which are fading in the spoken language. On the other hand, a Cantonese could learn to speak Standard Chinese, and read it alphabetically, at least as easily as he can learn several thousand characters.

Pinyin is used throughout this course to provide a simple written representation of pronunciation. The characters, which are chiefly responsible for the reputation of Chinese as a difficult language, are taught separately.

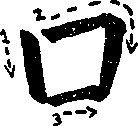

Each Chinese character is written as a fixed sequence of strokes. There are very few basic types of strokes, each with its own prescribed direction, length, and contour. The dynamics of these strokes as written with a brush, the classical writing instrument, show up clearly even in printed characters. You can tell from the varying thickness of the stroke how the brush met the paper, how it swooped, and how it lifted; these effects are largely lost in characters written with a ball-point pen.

The sequence of strokes is of particular importance. Let’s take the character for "mouth," pronounced kou. Here it is as normally written, with the order and directions of the strokes indicated.

If the character is written rapidly, in "running-style writing," one stroke glides into the next, like this.

If the strokes were written in any but the proper order, quite different distortions would take place as each stroke reflected the last and anticipated the next, and the character would be illegible.

The earliest surviving Chinese characters, inscribed on the Shang Dynasty "oracle bones" of about 1500 B.C., already included characters that went beyond simple pictorial representation. There are some characters in use today which are pictorial, like the character for "mouth." There are also some which are directly symbolic, like our Roman numerals I, II, and III. (The characters for these numbers—the first numbers you learn in this course—are like the Roman numerals turned on their sides.) There are some which are indirectly symbolic, like our Arabic numerals 1, 2, and 3. But the most common type of character is complex, consisting of two parts: a "phonetic," which suggests the pronunciation, and a "radical," which broadly characterizes the meaning. Let’s take the following character as an example.

This character means "ocean" and is pronounced yang. The left side of the character, the three short strokes, is an abbreviation of a character which means "water" and is pronounced shul. This is the "radical." It has been borrowed only for its meaning, "water." The right side of the character above is a character which means "sheep" and is pronounced yang. This is the "phonetic." It has been borrowed only for its sound value, yang. A speaker of Chinese encountering the above character for the first time could probably figure out that the only Chinese word that sounds like yang and means something like "water" is the word yang meaning "ocean." We, as speakers of English, might not be able to figure it out. Moreover, phonetics and radicals seldom work as neatly as in this example. But we can still learn to make good use of these hints at sound and sense.

Many dictionaries classify characters in terms of the radicals. According to one of the two dictionary systems used, there are 1?6 radicals; in the other system, there are 21U. There are over a thousand phonetics.

Chinese has traditionally been written vertically, from top to bottom of the page, starting on the right-hand side, with the pages bound so that the first page is where we would expect the last page to be. Nowadays, however, many Chinese publications paginate like Western publications, and the characters are written horizontally, from left to right.

A Chinese personal name consists of two parts: a surname and a given name. There is no middle name. The order is the reverse of ours: surname first, given name last.

The most common pattern for Chinese names is a single-syllable surname followed by a two-syllable given name:2

Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung)

Zhōu Ēnlái (Chou En-lai)

Jiang Jièshí (Chiang Kai-shek)

Song Qìnglíng (Soong Ch’ing-ling—Mme Sun Yat-sen)

Song Měilíng (Soong Mei-ling—Mme Chiang Kai-shek)

It is not uncommon, however, for the given name to consist of a single syllable:

Zhū De (Chu Teh)

Lin Biāo (Lin Piao)

Hu Shi (Hu Shih)

Jiang Qīng (Chiang Ch’ing—Mme Mao Tse-tung)

There are a few two-syllable surnames. These are usually followed by single-syllable given names:

Sīmǎ Guāng (Ssu-ma Kuang) Ōuyáng Xiū (Ou-yang Hsiu) Zhūgě Liang (Chu-ke Liang)

But two-syllable surnames may also be followed by two-syllable given names:

Sīmǎ Xiāngrú (Ssu-ma Hsiang-Ju)

An exhaustive list of Chinese surnames includes several hundred written with a single character and several dozen written with two characters. Some single-syllable surnames sound exactly alike although written with different characters, and to distinguish them, the Chinese may occasionally have to describe the character or "write" it with a finger on the palm of a hand. But the surnames that you are likely to encounter are fewer than a hundred, and a handful of these are so common that they account for a good majority of China’s population.

Given names, as opposed to surnames, are not restricted to a limited list of characters. Men's names are often but not always distinguishable from women’s; the difference, however, usually lies in the meaning of the characters and so is not readily apparent to the beginning student with a limited knowledge of characters.

Outside the People’s Republic the traditional system of titles is still in use. These titles closely parallel our own "Mr.," "Mrs.," and "Miss." Notice, however, that all Chinese titles follow the name—either the full name or the surname alone—rather than preceding it.

The title "Mr." is Xiānsheng.

MS Xiānsheng

JIS Mínglī Xiānsheng

The title "Mrs." is Tàitai. It follows the husband’s full name or surname alone.

MS Tàitai

MS Mínglī Tàitai

The title "Miss" is Xiǎojiě. The MS family’s grown daughter, Défēn, would be

Mǎ Xiǎojiě

MS Défēn XiSojiě

Even traditionally, outside the People’s Republic, a married woman does not take her husband’s name in the same sense as in our culture. If Miss Fang BSolán marries Mr. MS Mínglī, she becomes Mrs. MS Mínglī, but at the same time she remains Fāng BSolán. She does not become MS BSolán; there is no equivalent of "Mrs. Mary Smith." She may, however, add her husband’s surname to her own full name and refer to herself as Mǎ Fāng BSolán. At work she is quite likely to continue as Miss Fāng.

These customs regarding names are still observed by many Chinese today in various parts of the world. The titles carry certain connotations, however, when used in the PRC today: Tàitai should not be used because it designates that woman as a member of the leisure class. Xiǎojiě should not be used because it carries the connotation of being from a rich family.

In the People’s Republic, the title "Comrade," Tongzhì, is used in place of the titles Xiānsheng, Tàitai, and Xiǎojiě. Mǎ Mínglī would be

MS Tongzhì

Mǎ Mínglī Tongzhì

The title ’’Comrade" is applied to all, regardless of sex or marital status. A married'-woman does not take her husband’s name in any sense. MS Mínglí’s wife would be

Fang Tóngzhì

Fang Bǎolán Tóngzhì

Children may be given either the mother’s or the father’s surname at birth. In some families one child has the father's surname, and another child has the mother’s surname. MS MÍnglī’s and Fang BSolán's grown daughter could be

MS Tóngzhì

MS Défēn Tóngzhì

Their grown son could be

Fang Tóngzhì

Fang Zìqiáng Tóngzhì

Both in the PRC and elsewhere, of course, there are official titles and titles of respect in addition to the common titles we have discussed here. Several of these will be introduced later in the course.

The question of adapting foreign names to Chinese calls for special consideration. In the People’s Republic the policy is to assign Chinese phonetic equivalents to foreign names. These approximations are often not as close phonetically as they might be, since the choice of appropriate written characters may bring in nonphonetic considerations. (An attempt is usually made when transliterating to use characters with attractive meanings.) For the most part, the resulting names do not at all resemble Chinese names. For example, the official version of "David Anderson" is Dàiwéi Andésēn.

An older approach, still in use outside the PRC, is to construct a valid Chinese name that suggests the foreign name phonetically. For example, "David Anderson" might be An Dàwèi.

Sometimes, when a foreign surname has the same meaning as a Chinese surname, semantic suggestiveness is chosen over phonetic suggestiveness. For example, Wang, a common Chinese surname, means "king," so "Daniel King" might be rendered Wang Dànián.

Students in this course will be given both the official PRC phonetic equivalents of their names and Chinese-style names.

The Biographic Information Module provides you with linguistic and cultural skills needed for a simple conversation typical of a first-meeting situation in China. These skills include those needed at the beginning of a conversation (greetings, introductions, and forms of address), in the middle of a conversation (understanding and answering questions about yourself and your immediate family), and at the end of a conversation (leave-taking).

Before starting this module, you must take and pass the ORN Criterion Test. The resource modules Pronunciation and Romanization and Numbers (tapes 1-1») are also prerequisites to the BIO Module.

The Criterion Test will focus largely on this module, but material from Module 1 and associated resource modules may also be included.

OBJECTIVES

Upon successful completion of the module, the student should be able to

1. Pronounce correctly any word from the Target Lists of ORN or BIO, properly distinguishing sounds and tones, using the proper stress and neutral tones, and making the necessary tone changes.

2. Pronounce correctly any sentence from the BIO Target Lists, with proper pauses and intonation, that is, without obscuring the tones with English intonation.

3. Use polite formulas in asking and answering questions about identity (name), health, age, and other basic information.

h. Reply to questions with the Chinese equivalents of "yes” and "no.”

5. Ask and answer questions about families, including who the members are, how old they are, and where they are.

6. Ask and answer questions about a stay in China, including the date of arrival, location-purpose-duration of stay, previous visits, traveling companions, and date of departure.

7. Ask and answer questions about work or study—identification of occupation, the location, and the duration.

8. Give the English equivalent for any Chinese sentence in the BIO Target Lists.

9. Be able to say any Chinese sentence in the BIO Target Lists when cued with its English equivalent.

10. Take part in a short Chinese conversation, using expressions included in the BIO Target List sentences.

TAPES FOR BIO AND ASSOCIATED RESOURCE MODULES

Biographic Information (BIO)

|

Unit 1: Unit 2: |

1 C-l |

1 p-1 |

1&2 D-l |

1 C-2 |

1 P-2 2 P-2 | ||||||

|

2 |

C-2 | ||||||||||

|

2 |

C-l |

2 |

P-1 | ||||||||

|

Unit |

3: |

3 |

C-l |

3 |

P-1 |

3&U |

D-l |

3 |

C-2 |

3 |

P-2 |

|

Unit |

U: |

U |

C-l |

1» |

P-1 |

U |

C-2 |

U |

P-2 | ||

|

Unit |

5: |

5 |

C-l |

5 |

P-1 |

5&6 |

D-l |

5 |

C-2 |

5 |

P-2 |

|

Unit |

6: |

6 |

C-l |

6 |

P-1 |

6 |

C-2 |

6 |

P-2 | ||

|

Unit |

7: |

7 |

C-l |

7 |

P-1 |

7&8 |

D-l |

7 |

C-2 |

7 |

P-2 |

|

Unit |

8: |

8 |

C-l |

8 |

P-1 |

8 |

C-2 |

8 |

P-2 | ||

Units 1-1» R-l

Units 5-8 R-l

Classroom Expressions (CE)

CE 2

Time and Dates (T&P)

T&D 1 T&D 2

UNIT 1 TARGET LIST

1. Qingwèn, nl zhù zai nǎr?

Wo zhù zai Beijing Fàndiàn.

2. Ni zhù zai něige fàndiàn?

W3 zhù zai nèige fàndiàn.

3. Nl zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma?

Bù, wó bú zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

U. Nī zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn ma?

Bù, w3 bú zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn.

5. Něiwèi shi Gāo Tóngzhì?

Neiwèi shi Gāo Tóngzhì.

6. Z&o. Nuòwākè Nushì! Nín hǎo.

W5 hen hāo.

7. Ni shi Měiguo nǎrde rén?

Wó shi Jiāzhōu Jiùjlnshān rén.

May I ask, where are you staying? I'm staying at the BSijlng Hotel.

Which hotel are you staying at?

I'm staying at that hotel.

Are you staying at this hotel?

No, I'm not staying at this hotel.

Are you staying at the Nationalities Hotel?

No, I'm not staying at the Nationalities Hotel.

Which one is Comrade Gāo?

That one is Comrade Gāo.

Good morning. Miss Novak.' How are you.

I'm very well.

Where are you from in America?

I’m from San Francisco, California.

UNIT 2 TARGET LIST

1. Nì péngyou jiā zài náli?

Tā jiā zài Dàli Jiē.

2. Ni péngyoude dìzhl shi...?

Tāde dìzhí shi Dàlǐ Jiē Sìshièr-hào.

Where is your friend's house?

His house is on Dàll Street.

What is your friend’s address?

His address is No. U2 Dàll Street

3. NX shi Wèi Shàoxiào ba?

Shide.

U. Nà shi Guóbīn Dà fan di an ba?

Shide, nà shi Guobīn Dàfàndiàn.

NX zhù zai nàli ma?

Bù, wō zhù zai zhèli.

5. NX péngyou zài TaibSi gōngzuò ma?

Tā bú zài TáibSi gōngzuò; tā zài Taizhōng gōngzuò.

6. NX zài náli gōngzuò?

NX zài Wǔguānchù gōngzuò.

OR

Wō zài yínháng gōngzuò.

You are Major Weiss, aren’t you?

Yes.

That is the Ambassador Hotel, isn't it?

Yes, that's the Ambassador Hotel.

Are you staying there?

No, I'm staying here.

Does your friend work in Taipei?

He doesn't work in Taipei; he works in Taichung.

Where do you work?

I work at the defense attache's office.

I work at a bank.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

7. lù road

UNIT 3 TARGET LIST

1. NXmen yōu háizi ma?

Yōu, wōmen yōu.

2. Liu Xiānsheng méiyou Méiguo péngyou.

3. Nimen yōu jXge nánháizi, jlge nǔháizi?

Wōmen yōu liǎngge nánháizi, yíge niiháizi.

Do you have any children?

Yes, we have.

Mr. Liu doesn't have any American friends.

How many boys and how many girls do you have?

We have two boys and one girl.

U. Hu Xiānsheng Hu Tàitai you Jīge háizi?-

Tāmen y$u liǎngge háizi.

Shi nánháizi, shi nūháizi?

Dōu shi nūháizi.

5. Nīmen háizi dōu zài zhèli ma?

Bù, liangge zài zhèli, yíge hái zài Měiguō.

6. Nl Jiāli y5u shénme rén?

YSu wo tàitai gēn sānge háizi.

7. Ní Jiāli you shénme rén?

Jiù you w3 fùqin, mǔqin

How many children do Mr. and Mrs. Hú have?

They have two children.

Are they boys or girls?

Both of them are girls.

Are all your children here?

No. Two are here, and one is still in America.

What people are in your family?

There’s my wife and three children.

What people are in your family?

Just my father and mother.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

|

8. |

zhí |

only |

|

9. |

dìdi |

younger brother |

|

10. |

gēge |

older brother |

|

11. |

JièJie |

older sister |

|

12. |

mèimei |

younger sister |

|

13. |

xiōngdì |

brothers |

|

1U. |

JiSmèi |

sisters |

|

15. |

xiōngdì JiSmèi |

brothers and sisters |

|

16. |

fùmǔ |

parents |

|

17. |

zūfù |

paternal grandfather |

|

18. |

zǔmǔ |

paternal grandmother |

|

19. |

wàizǔfù |

maternal grandfather |

|

20. |

wàizǔmǔu |

maternal grandmother |

|

21. |

bàba |

papa, dad, father |

|

22. |

mama |

momma, mom, mother |

UNIT 4

1. Tā míngtiān lai ma?

Tā yījīng lai le.

2. Nī péngyou lai le ma?

Tā hāi méi(you) lai.

3. Tā shi shénme shíhou dàode? Tā shi zuotiān dàode.

U. NX shi yíge rén láide ma? Bú shi, wǒ bú shi yíge rén JLàide.

5. Nī néitiān zǒu?

Wǒ jīntiān zǒu.

TARGET LIST

Is he coming tomorrow? He has already come.

Has your friend come?

She hasn't come yet.

When did he arrive?

He arrived yesterday.

Did you come alone?

No, I didn't come alone.

What day are you leaving?

I'm leaving today.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

|

6. |

hòutiān |

the day after tomorrow |

|

7. |

qiàntiān |

the day before yesterday |

|

8. |

tiāntiān |

every day |

|

9. |

érzi |

son |

|

10. |

nuer |

daughter |

UNIT 5 TARGET LIST

1. Nī shi zài nǎr shēngde?

Wǒ shi zài Dézhōu shēngde.

2. Nīmen xīngqījī zǒu?

Women Xīngqītiān zǒu.

Where were you born?

I was born in Texas.

What day of the week are you leaving?

We are leaving on Sunday.

3. Nī shi nēinián shēngde?

Wǒ shi Yījiǔsānjifinián shēngde.

U. Nī shi jīyǔè jīhào shēngde?

Wǒ shi QÍyǔe sìhào shēngde.

5. Nī duō dà le?

Wǒ sānshiwǔ le.

6. Nīmen nanháizi dōu jīsuì le?

YÍge jiǔsuì le, yíge liùsuì le.

What year were you born?

I was born in 1939.

What is your month and day of birth?

I was born on July U.

How old are you?

I’m 35.

How old are your boys?

One is nine, and one is six.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

7. hòunián

8. jīnián

9. míngnián

10. qiánnián

11. qunian

12. niánnián

the year after next this year next year

the year before last last year every year

UNIT 6 TARGET LIST

1. Nī zhù duo jiǔ?

Wǒ zhù yìnián.

2. Nī tàitai zài Xiānggāng zhù duo jiǔ?

Wǒ xiāng tā zhù liāngtiān.

3. Nī xiāng zài Taiwan zhù duǒ jiǔ?

Wǒ xiāng zhù liùge yǔè.

U. Nī láile duo jiǔ le?

Wǒ láile liāngge xīngqī le.

How long are you staying?

I’m staying one year.

How long is your wife staying in Hong Kong?

I think she is staying two days.

How long are you thinking of staying in Taiwan?

I'm thinking of staying six months.

How long have you been here?

I have been here two weeks.

5. NX tàitai zài Xianggang zhùle duo Jiǔ?

Tā zhùle liǎngtiān.

6. Lī Tàitai méi lai.

7. NX cōngqián láiguo ma?

Wō cóngqián méi laiguo. Wō tàitai láiguo.

How long did your wife stay in Hong Kong?

She stayed two days.

Mrs. Li didn’t come.

Have you ever been here before?

I have never been here before. My wife has been here.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

8. qfi to go

9. Niù Yūē New York

UNIT 7 TARGET LIST

1. Nín zài náli gōngzuò?

Wō zài MSiguo Guōwùyuàn gōngzuò.

2. NX zài náli gōngzuò?

Wō shi xùésheng.

3. NX lái zuò shénme?

Wō lái niàn shū.

h. NX niàn shénme?

Wō xtté Zhōngwén.

5. NX zài dàxùé niànguo lìshX ma? Niànguo.

6. Nīmen huì shuō Zhōngwén ma?

Wō tàitai bú huì shuō, wō huì shuō yìdiǎn.

Where do you work?

I work with the State Department.

Where do you work?

I’m a student.

What did you come here to do?

I came here to study.

What are you studying?

I’m studying Chinese.

Did you study history in college?

Yes.

Can you speak Chinese?

My wife can’t speak it; I can speak a little.

7. Nīde Zhōngguo huà hSn hǎo.

Nall, náli. W3 jlù huì shuō yìdiān.

8. Nī shi zài náli xuéde Zhōngwén?

W6 shi zài Huáshèngdùn xiiéde.

Your Chinese is very good.

Not at all, not at all. I can speak only a little.

Where did you study Chinese?

I studied it in Washington.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

|

9. |

JīngJixUé |

economics |

|

10. |

Rìwén |

Japanese language |

|

11. |

wenxue |

literature |

|

12. |

zhèngzhixiié |

political science |

|

13. |

nan |

to be difficult |

|

Ih. |

rōngyi |

to be easy |

|

15. |

xiiéxí (xuéxi) |

to study, to learn (PRC) |

UNIT 8 TARGET LIST

1. Nī jīntiān hái you kè ma?

Meiyou kè le.

2. Nī cóngqián niàn Yīngwén niànle duō jiǔ?

W5 niàn Yīngwén niànle liùnián.

3. Nī niàn Fàwén niànle duo jiǔ le?

W3 niànle yinian le.

h. Qunián wō hái bú huì xiě Zhōngguo zì.

Xiànzài w3 huì xiě yìdiān le.

5. Nī fùqin shi jùnrén ma?

Shi, tā shi hāijǔn Junguān.

Do you have any more classes today? I don't have any more classes.

How long did you study English?

I studied English for six years.

How long have you been studying French?

I've been studying it for one .year.

Last year I couldn’t write Chinese characters.

Now I can write a little.

Is your father a military man?

Yes, he's a naval officer.

W3 bìng le.

Jintiān hao le. ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

|

I’m not coming today. I'm sick. Are you better today' Today I'm better. air force army enlisted man to work German language |

UNIT 1

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Where people are staying (hotels).

2. Short answers.

3. The question word néige, "which."

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-1 tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The C-2 and P-2 tapes, the Workbook.

3. The drill tape (1D-1).

(in Béijīng)

|

1. |

A: B: |

Qīngwèn, nī zhù zai nǎr? W6 zhù zai Bāijīng Fàndiàn. |

May I ask, where are you staying? I’m staying at the Béijīng Hotel. |

|

2. |

B: |

Nī zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn |

Are you staying at the Nationalities |

|

ma? |

Hotel? | ||

|

A: |

Shi, wS zhù zai Mínzú |

Yes, I’m staying at the Nationalities | |

|

Fàndiàn. |

Hotel. | ||

|

3. |

A: |

Nī zhù zai něige fàndiàn? |

Which hotel are you staying at? |

|

B: |

W5 zhù zai Běijīng Fàndiàn. |

I’m staying at the Běijīng Hotel. | |

|

1*. |

B: |

Nèiwèi shi Zhāng Tongzhì? |

Which one is Comrade Zhāng? |

|

A: |

Tā shi Zhāng Tongzhì. |

She is Comrade Zhāng. | |

|

5-* |

B: |

Něige rén shi Méi Tongzhì? |

Which person is Comrade Mei? |

|

A: |

Nèige rén shi Méi Tongzhì. |

That person is Comrade Méi. |

6. B: Něiwèi shi Gāo Tóngzhì?

A: Nèiwèi shi Gāo Tǒngzhì.

7.3 A: Hi zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma?

B: Bù, wǒ bú zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

8. B: Jiang Tongzhì! Nín zāo.

A: Zāo. Nuowǎkè Nushì! Nín hāo.

B: Wǒ hen hāo.

9. A: QXngwèn, ni shi Měiguo nārde rén?

B: Wǒ shi Jiāzhōu Jiùjlnshān rén.

Which one is Comrade Gāo?

That one is Comrade Gāo.

Are you staying at this hotel?

No, I’m not staying at this hotel.

Comrade Jiāng! Good morning.

Good morning. Miss Novak! How are you.

I’m very well.

May I ask, where are you from in America?

I’m from San Francisco, California.

|

fàndiàn |

hotel |

|

-ge hěn |

(general counter) very |

|

JiùjInshān Mínzú Fàndiàn |

San Francisco Nationalities Hotel |

|

něi-něige? nèige něiwèi? nèiwèi nushì |

which which? that which one (person)? that one (person) (polite title for a married or unmarried woman) Ms.; lady |

|

Shi. |

Yes, that’s so. |

|

-wèi |

(polite counter for people) |

|

Zāo. zhèi-zhèige zhèiwèi zhù |

Good morning. this this this one (person) to stay, to live |

1. A: Qlngwèn, ni zhù zai nār? May I ask, where are you staying?

B: WS zhù zai BSiJing Fàndiàn. I'm staying at the BéiJIng Hotel.

Notes on No. 1

The verb zhù, "to live," or "to reside," may be used to mean "to stay at" (temporary residence) or "to live in" (permanent residence).

Zhù zai nār literally means "live at where." The verb zài, "to be in/ at/on,” is used here as a preposition, "at." It loses its tone in this position in a sentence. (The use of zài as a preposition is treated more fully in Unit 2.)

Fàndiàn has two meanings—"restaurant" and "hotel" (a relatively large hotel with modern facilities).* Literally, fàndiàn means "rice shop."

2. B: Ni zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn ma? Are you staying at the Nationalities Hotel?

A: Shi, wS zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn. Yes, I'm staying at the Nationalities Hotel.

Note on No. 2

Shi; The usual way to give a short affirmative answer is to repeat the verb used in the question. Some verbs, however, may not be repeated as short answers. Zhù is one such verb. Others not to be used are xìng, "to be surnamed," and jiào, "to be given-named." Many speakers do not repeat the verb zài as a short answer. To give a short "yes" answer to questions containing these verbs, you use shi.

3. A: Ni zhù zai něige fàndiàn?

B: WS zhù zai Beijing Fàndiàn.

U. B: Něiwèi shi Zhang Tóngzhì?

A: Tā shi Zhang Tóngzhì.

Which hotel are you staying at? I'm staying at the Běijīng Hotel.

Which one is Comrade Zhāng? She is Comrade Zhāng.

5. B: Nèige rén shi Méi Tongzhì?

A: Nèige rén shi Méi Tongzhì.

6. B: Neiwèi shi Gāo Tongzhì?

A: Nèiwèi shi Gāo Tongzhì.

7. A: Nī zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma?

B: Bù, w3 hú zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

Which person is Comrade Mei?

That person is Comrade Méi.

Which one is Comrade Gāo? That one is Comrade Gāo.

Are you staying at this hotel?

No, I’m not staying at this hotel

Notes on Nos. 3-7

Nèige is the question word "which." In the compound nèiguó, you found the hound word nèi-, which was attached to the noun guó. In the phrase nèige rén, "which person," the hound word něi- is attached to the general counter -ge. (You will learn more about counters in Unit 3. For now, you may think of -ge as an ending which turns the hound word nèi- into the full word nèige.)

Nèige rén/Nèiwèi: To he polite when referring to an adult, you say nèiwèi or nèiwèi, using the polite counter for people -wèi rather than the general counter -ge. though -ge is used in many informal situations.

Notice that the noun rén is not used directly after -wèi:

|

Nèiwèi |

Mèiguo rén |

shi shéi? |

|

Nèiwèi |

zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn? |

Compare the specifying words "which?" "that," and "this" with the location words you learned in Unit U of ORN:

specifying words

|

nèige? |

(nāge?) |

(which?) |

|

nèige |

(nàge) |

(that) |

|

zhèige |

(zhège) |

(this) |

location words

|

nǎr? |

(where?) | |

|

nàr |

(nèr) |

(there) |

|

zhèr |

(zhàr) |

(here) |

Both question words are in the Low tone, while the other four words are in the Falling tone.

Many people pronounce the words for "which?" "that," and "this" with the usual vowels for "where?" "there," and "here": nǎge? nàge, and zhège.

Bù: A short negative answer is usually formed by bù plus a repetition of the verb used in the question. When a verb, like zhví (zai), cannot be repeated, bù is used as a short answer and is followed by a complete answer. Notice that when used by itself bù is in the Falling tone, but when followed by a Falling-tone syllable bù is ih the Rising tone.

Bù, tā xiànzai bú zài zher. No, he's not here now.

8. B: Jiang Tóngzhì! Nín zāo.

A: Zāo. Nuòwākè Nushì! Nín hāo.

B: Wǒ hen hāo.

Comrade Jiāng! Good morning.

Good morning. Miss Novak! How are you.

I'm very well.

Notes on No. 8

Name as greeting: A greeting may consist simply of a person's name: Wang Tóngzhì! "Comrade Wáng!" The name may also be used with a greeting phrase: Wáng Tóngzhì! Nín zāo. "Comrade Wáng! Good morning."--or, in reverse order, Nín zāo. Wang Tóngzhì! "Good morning. Comrade Wáng!" The name is pronounced as an independent exclamation acknowledging that person's presence and status. It is not de-emphasized like "Comrade Wáng" in the English sentence "Good morning, Comrade Wáng."

Nín zāo means "good morning"—literally, "you are early." You may also say either nì zāo or simply zāo.

Nushì, "Ms.," is a formal, respectful title for a married or unmarried woman. It is used after a woman's own surname, not her husband's. Traditionally, this title was used for older, educated, and accomplished women. In the PRC, where people use Tóngzhì, "Comrade," in general only foreign women are referred to and addressed as (so-and-so) Nushì. On Taiwan, however, any woman may be called (so-and-so) Nushì in a formal context, such as a speech or an invitation.

Nín hāo: This greeting may be said either with or without a question marker, just as in English we say "How are you?" as a question or "How are you" as a simple greeting.

Nǐ hāo ma? How are you?

Nì hāo. How are you.

Also Just as in English, you may respond to the greeting by repeating it rather than giving an answer.

Lì Tóngzhì! Nín hāo. Comrade Lì! How are you.

Nín hāo. Gāo Tóngzhì! How are you. Comrade Gāo!

Literally, hSn means ’’very." The word often accompanies adjectival verbs (like h&o, "to be good"), adding little to their meaning. (See also Module 3, Unit 3.)

How to identify yourself: You have now learned several ways to introduce yourself. One simple, direct way is to extend your hand and state your name in Chinese—for instance, Mǎ Mínglì. Here are some other ways:

W8 shi MS Mínglì. I am MS Mínglì.

Wǒ xìng MS. My surname is MS.

Wǒ xìng MS, Jiào MS Mínglì. My surname is MS; I am called MS Mínglì.

WSde Zhōngguo míngzi Jiao My Chinese name is MS MÍnglì. MS MÍnglì.

9. A: Qlngwèn, nī shi Měiguo nSrde rén?

B: Wō shi Jiāzhōu Jiùjīnshān rén.

May I ask, where are you from in America?

I’m from San Francisco, California.

Notes on No. 9

Order of place names: Notice that Jiāzhōu Jiùjīnshān is literally "California, San Francisco." In Chinese, the larger unit comes before the smaller. Similarly, in the question Nī shi Meiguo nǎrde rén? the name of the country comes before the question word nǎr, which is asking for a .mere detailed location. The larger -unit is usually repeated in the answer:

|

Nī shi |

Shandong I |

nār |

1 S' 1 ____1 |

i éi.? |

1 1 |

|

Wǒ shi |

Shandong | |

Cīngdǎo |

! 'í GA |

Literally, Jiùjīnshān means "Old Gold Mountain." name to San Francisco during the Gold Bush days.

The Chinese gave this

A. Response Drill

Respond according to the cues.

1. Speaker: Tā zhù zai nǎr?

(cue) Běijīng Fàndiàn

(Where is he/she

staying?)

2. Nī àiren zhù zai nǎr?

Mínzú Fàndiàn

(Where is your spouse staying?)

3. Li Tongzhì zhù zai nǎr?

zhèige fàndiàn

(Where is Comrade LĪ staying?)

U. Fāng Tongzhì zhù zai nār?

nèige fàndiàn

(Where is Comrade Fāng staying?)

5. Chen Tongzhì zhù zai nǎr?

Běijīng Fàndiàn

(Where is Comrade Chen staying?)

6. LÍn Tongzhì zhù zai nǎr?

Mínzú Fàndiàn

(Where is Comrade LÍn staying?)

7. Huang Tongzhì zhù zai nǎr?

zhèige fàndiàn

(Where is Comrade Huǎng staying?)

You: Tā zhù zai Běijīng Fàndiàn. (He/she is staying at the

Beijing Hotel.)

Tā zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at the Nationalities Hotel.)

Tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at this hotel.)

Tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at that hotel.)

Tā zhù zai Běijīng Fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at the Beijing

Hotel.)

Tā zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at the Nationalities Hotel.)

Tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at this hotel.)

B. Response Drill

Give affirmative responses to all questions.

1. Speaker: Gāo Nushì zhù zai You: Shi, tā zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn.

Mínzú Fàndiàn ma? (Yes, she is staying at the

(Is Miss Gáo staying Nationalities Hotel.)

at the Nationalities Hotel?)

2. Zhāng Nushì zhù zai Běijīng Shi, tā zhù zai Běijīng Fàndiàn.

Fàndiàn ma?

3. Jiāng Nushì zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma?

’i. Huang Nushì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn ma?

5. Wang Nushì zhù zai BSijlng Fàndiàn ma?

6. LÍn Nushì zhù zai MÍnzú Fàndiàn ma?

7. Mao Nushì zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma?

Shi, tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

Shi, tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn.

Shi, tā zhù zai Bèijìng Fàndiàn

Shi, tā zhù zai MÍnzú Fàndiàn.

Shi, tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

C. Response Drill

Give negative responses to all

1. Speaker: Jiāng Xiānsheng zhù zai zhège fàndiàn ma?

(Is Mr. Jiāng staying at this hotel?)

2. MS Xiānsheng zhù zai nàge fàndiàn ma?

3. Lì Xiānsheng zhù zai Guobīn Dàfàndiàn ma?

U. Zhào Xiānsheng zhù zai Yuánshān Dàfàndiàn ma?

5. Liú Xiānsheng zhù zai Yuánshān Dàfàndiàn ma?

6. Tang Xiānsheng zhù zai nàge fàndiàn ma?

7. Song Xiānsheng zhù zai zhège fàndiàn ma?

questions.

You: Bu shi, tā bú zhù zai zhège fàndiàn.

(No, he isn’t staying at this hotel.)

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai nàge fàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai Yuánshān Dàfàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai Yuánshān Dàfàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai nàge fàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai zhège fàndiàn

D. Response Drill

the

Give either a negative or an affirmative response, according to cues.

1. Speaker: Tang Tongzhì zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma? (cue) zhèige fàndiàn

(Is Comrade Tang staying at this hotel?)

OR Ma Tongzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn ma? (cue) zhèige fàndiàn (Is Comrade MS staying at this hotel?)

2. Mǎ Tongzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn ma? zhèige fàndiàn

3. LĪ Tongzhì zhù zai Bǎijīng Fàndiàn ma? Bǎijīng Fàndiàn

U. Zhào Tongzhì zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn ma? Bǎijīng Fàndiàn

5. Liu Tongzhì zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn ma? nèige fàndiàn

6. Jiang Tongzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn ma? nèige fàndiàn

7. Zhāng Tongzhì zhù zai Bǎijīng Fàndiàn ma? Mínzú Fàndiàn

You: Shi, tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn (Yes, he is staying at this hotel.)

Bú shi, tā hú zhù zai nèige fàndiàn.

(No, he isn't staying at that hotel.)

Bú shi, tā hú zhù zai nèige fàndiàn

Shi tā zhù zai Bǎijīng Fàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn.

Shi, tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn.

Bú shi, tā bú zhù zai Bǎijīng Fàndiàn.

E. Transformation Drill

Change the less polite forms nèige forms nèiwèi and zhèiwèi.

1. Speaker: Nèige rén shi LÍ

Tongzhì.

(That person is Comrade LI.)

2. Zhèige rén shi Fāng Tongzhì.

3. Nèige rén shi Jiāng Tongzhì.

rén and zhèige rén to the more polite

You: Nèiwèi shi Li Tongzhì.

(That one is Comrade LĪ.)

Zhèiwèi shi Fāng Tongzhì.

Nèiwèi shi Jiāng Tongzhì.

|

2. |

Zhāng Tóngzhì zhù zai nèige |

Tā zhù zai Bèijīng Fàndiàn. |

|

fàndiàn? Bèijīng Fàndiàn | ||

|

3. |

Jiāng Tóngzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn? nèige fàndiàn |

Tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn. |

|

U. |

Wang Tóngzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn? zhèige fàndiàn |

Tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn. |

|

5. |

Huáng Tóngzhì zhù. zai nèige fàndiàn? Mínzú Fàndiàn |

Tā zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn. |

|

6. |

Lin Tóngzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn? Bèijīng Fàndiàn |

Tā zhù zai Bèijīng Fàndiàn. |

|

7. |

Liú Tóngzhì zhù zai nèige fàndiàn? zhèige fàndiàn |

Tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn. |

U. Zhèige rén shi Zhōu Tongzhì.

5. Nèige rén shi Zhāng Tongzhì.

6. Zhèige rén shi Chén Tóngzhì.

7. Nèige rén shi Hú Tóngzhì.

Zhèiwèi shi Zhōu Tóngzhì.

Nèiwèi shi Zhāng Tóngzhì.

Zhèiwèi shi Chén Tóngzhì.

Nèiwèi shi Hu Tóngzhì.

F. Response Drill

Respond to nèige fàndiàn? "which hotel?" according to the cues.

1. Speaker: Tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn?

(cue) Mínzú Fàndiàn

(Which hotel is he/she staying at?)

You: Tā zhù zai Mínzú Fàndiàn. (He/she is staying at the Nationalities Hotel.)

G. Response Drill

Respond to nèige rén? "which person?" with nèige rén, "that person."

1. Speaker: Qlngwèn, nèige rén shi You: Nèige rén shi Wang Déxián.

Wang Déxián? (That person is Wang Déxián.)

(May I ask, which person

is Wang Déxián?)

2. Qíngwèn, nèige rén Shimin?

3. Qíngwèn, nèige rén Bǎolán?

1*. Qíngwèn, nèige rén Tíngfēng?

5. Qingwèn, nèige rén Wǎnrú?

6. Qíngwèn, nèige rén Mèilíng?

7. Qíngwèn, nèige rén Zhīyuǎn?

shi Zhao Nèige

shi Lin Nèige

shi Gāo Nèige

shi Zhang Nèige

shi Hu Nèige

shi Sòng Nèige

rén shi Zhao Shinin, rén shi Lin Bǎolán.

rén shi Gāo Tíngfēng rén shi Zhāng Wǎnrú.

rén shi Hú Mèilíng.

rén shi Song Zhīyuǎn

H. Transformation Drill

Ask the appropriate "which” or ’’where” question according to statements.

1. Speaker: Tā lǎojiā zài Qingdao. (His/her family is from Qingdao.)

OR Tā xiànzài zài Jiānádà. (He/she is in Canada now.)

OR Tā zhù zai Bèijīng Fàndiàn.

(He/she is staying at the Bèijing Hotel.)

2. Tā xiànzài zài Shāndōng.

(He/she is in Shāndōng now.)

3* Tā zhù zai MÍnzú Fàndiàn. (He/she is staying at the Nationalities Hotel.)

U. Tā lǎojiā zài Húbèi. (His/her family is from Hubei.)

5. Tā xiànzài zài Mèiguō.

(He/she is in America now.)

You? Tā lǎojiā zài nǎr?

(Where is his/her family from?)

Tā xiànzài zài nǎr? (Where is he/she now?)

Tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn?

(in which hotel is he/she staying?)

Tā xiànzài zài nǎr?

(Where is he/she now?)

Tā zhù zai nèige fàndiàn?

(In which hotel is he/she staying?)

Tā lǎojiā zài nǎr?

(Where is his/her family from?)

Tā xiànzài zài nǎr?

(Where is he/she now?)

ó. Tā zhù zai zhèige fàndiàn. (He/she is staying at this hotel.)

7. Tā lāojiā zài Guangdong. (His/her family is from Guangdong.)

Tā zhù zai neige fàndiàn?

(In which hotel is he/she staying?)

Tā lāojiā zài nǎr?

(Where is his/her family from?)

Pagoda in central Taiwan (courtesy of Thomas Madden)

UNIT 2

Topics Covered in Tills Unit

1. Where people are staying (houses).

2. Where people are working.

3. Addresses.

U. The marker de.

5. The marker ba.

6. The prepositional verb zài.

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-1 tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The C-2 and P-2 tapes, the Workbook.

3. The 2D-1 tape.

(in Taipei)

|

1. |

A: B: |

Nì zhù zai náli? |

Where are you staying? I’m staying at the Ambassador Hotel |

|

Wǒ zhù zai Guōbīn Dàfàndiàn. | |||

|

2. |

A: |

Nī zhù zai náli? |

Where are you staying? |

|

B: |

Wǒ zhù zai zhèli. |

I’m staying here. | |

|

A: |

Tā ne? |

How about him? | |

|

B: |

Tā zhù zai nàli. |

He is staying there. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Nī zhù zai náli? |

Where are you staying? |

|

B: |

Wǒ zhù zai péngyou jiā. |

I’m staying at a friend’s house. | |

|

U. |

A: |

Nī péngyou jiā zài náli? |

Where is your friend’s house? |

|

B: |

Tā jiā zài Dàlī Jiē. |

His house is on Dàlī Street. | |

|

5. |

A: |

Nī péngyoude dìzhī shi...? |

What is your friend’s address? |

|

B: |

Tāde dìzhī shi Dàlī Jiē Sìshièrhào. |

His address is No. 1*2 Dàlī Street. | |

|

6. |

* A: |

Nī shi Wèi Shàoxiào ba? |

You are Major Weiss, aren’t you? |

|

B: |

Shide. |

Yes. | |

|

7. |

**A: |

Nà shi Guobīn Dàfàndiàn ba? |

That is the Ambassador Hotel, isn’t it? |

|

B: |

Shìde. |

Yes. | |

|

8. |

A: |

Nī péngyou xiànzài zài náli gōngzuò ? |

Where does your friend work now? |

|

B: |

Tā zài Táinán gōngzuò. |

He works in Tainan. | |

|

9. |

* A: |

Nī zài náli gōngzuò? |

Where do you work? |

|

B: |

Wǒ zài Wǔguānchù gōngzuò. |

I work at the defense attache’s office. | |

|

10. |

**A: |

Nī zài náli gōngzuò? |

Where do you work? |

|

B: |

Wǒ zài yínháng gōngzuò. |

I work at a bank. |

Does your friend work in Taipei?

He doesn’t work in Taipei; he works in Taichung.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes) 12. lù

road

|

ba |

(question marker expressing supposition of what answer will be) |

|

dàfàndiàn -de dìzhl |

hotel (possessive marker) address |

|

gōngzud Guóbln Dàfàndiàn |

to work Ambassador Hotel |

|

-hào |

number (in addresses) |

|

Jiā Jiē |

home, house street |

|

lù |

road |

|

nà-nàge náli nàli |

that that (one) where there |

|

péngyou |

friend |

|

shàoxiào Shìde. |

major (military title) Yes, that's so. |

|

Wǔguānchù |

defense attache's office |

|

yínháng |

bank |

|

zài zhè-zhège zhèli |

to be in/at/on (prepositional verb) this this (one) here |

(introduced on C-2, P -2, and, drill tapes)

Dìyī Dàfàndiàn

Máiguo Guójì Jiāoliú

Zòngshǔ

Meiguo Yínháng

Taiwan Yínháng youzhèngju

First Hotel

U.S. International

Communications Agency

Bank of America Bank of Taiwan post office

11U

|

1. |

A: B: |

Nī zhù zai náli? W3 zhù zai Guébīn Dàfàndiàn. |

Where are you staying? I'm staying at the Ambassador Hotel. |

|

2. |

A. |

Nī zhù zai náli? |

Where are you staying? |

|

B: |

Wo zhù zai zhèli. |

I'm staying here. | |

|

A: |

Tā ne? |

How about him? | |

|

B: |

Tā zhù zai nàli. |

He is staying there. |

Notes on Nos. 1-2

The word guébīn actually refers to any official state guest, not just an ambassador.(The word for ’’ambassador” is dàshī.) The translation "Ambassador Hotel" has been used for years by that hotel and, although inaccurate, has been retained in this text.

Dàfàndiàn means "great hotel" or "grand hotel." It is commonly used in the names of Taiwan and Hong Kong hotels.

Náli, nàli, and zhèli are common variants of nār, nàr, and zhèr in non-Peking dialects of Standard Chinese. The forms with r sire Peking dialect forms. Compare:

Peking Other

|

nār? |

náli? |

(where?) |

|

nàr |

nàli |

(there) |

|

zhèr |

zhèli |

(here) |

Notice the difference in tone between nǎr and náli. This is because -li has a basic Low tone, and the first of two adjoining Low-tone syllables changes to a Rising tone: nǎ + -11 = náli

3. A: . Nī zhù zai náli?

B: W3 zhù zai péngyou jiā.

U. A: Nī péngyou jiā zài náli?

B: Tā jiā zài Dàlī Jiē.

Where are you staying?

I’m staying at a friend’s house.

Where is your friend’s house?

His house is on Dàll Street.

Note on Nos. 3-U

The possessive relationships in péngyou jiā, ’’friend’s house,” nì péngyou jiā, ’’your friend’s house," and tā jiā, "his house," are unmarked, while the English must include -’s. or the possessive form of the pronoun ("your," "his"). In Chinese, possessive relationships may be expressed by simply putting the possessor in front of the possessed when the relationship between the two is particularly close, like the relationship between a person and his home, family, or friends.

5. A: Nì péngyoude dìzhī shi...? B: Tāde dìzhī shi Dàlī Jiē Sìshièrhào.

What’s.your friend’s address? His address is No. U2 Dàlī Street.

Notes on No. 5

Péngyoude dìzhī: The marker -de in this phrase is Just like the English possessive ending -*£. With the exception of close relationships, this is the usual way to form the possessive in Chinese.

|

nī |

péngyou |

-de |

dìzhī |

|

(your |

friend |

’s |

address) |

Unlike the English -*£ ending, -de is also added to pronouns.

|

wǒde |

(my) |

|

nīde |

(your) |

|

tāde |

(his/her) |

You are learning possessive phrases in which the marker -de is used (tāde dìzhī) and some possessive phrases which do not contain -de (nī péngyou jiā). There are certain reasons for the inclusion or omission of -de. If a close relationship exists between the possessor and the possessed, the marker -de might not be used. If a phrase is long and complex, as Lī Xiānsheng péngyoude tàitai, the marker -de is used to separate the possessor from the possessed.

short or simple

long or complex

nī jiā

wǒ péngyou

Hú Meilíng -de l&ojiā

nī péngyou -de dìzhī

Lī Xiānsheng péngyou -de tàitai

But these are not hard and fast rules. The use or omission of -de is not determined solely by the number of syllables in a phrase or by the closeness between the possessor and the possessed, although both of these considerations do play a big part in the decision.

While some common nouns are usually used without -de before them, most nouns are more likely to be preceded by -de, and many even require it. Dìzhl, "address,” is the only noun you have learned which REQUIRES the possessive marker -de added to the possessor. But other nouns such as Jiá are not always preceded by -de. This is also the case with nouns indicating personal relationships, like fùmǔ, ’’father," and tàitai, "wife." Pěngyou, "friend," xuésheng, "student," and l&oshl, "student." are commonly used without -de, but may also be used with the marker.

You might expect the question Nī péngyoude dìzhl shi...? to be completed with a word such as shénme. "what.11However, the incomplete form given in this exchange, with the voice trailing off, inviting completion, is also commonly used.

Addresses: The order in which addresses are given in Chinese is the reverse of that used in English. In Chinese, the order is from the general to the specific: country, province or state, city, street name, street number.

-hào: A street number is always given with the bound word -hào, "number," after it.6

6. A: Nī shi Wei Shàoxiào ba?

B: Shìde.

7. A: Nèi shi Guóbln Dàfàndiàn ba?

B: Shìde.

You are Major Weiss, aren’t you?

Yes.

That is the Ambassador Hotel, isn’t it?

Yes.

Notes on Nos. 6-7

Ba is a marker for a question which expresses the speaker's supposition as to what the answer will be. It is the type of question which asks for a confirmation from the listener.

There are three ways to translate the two questions in exchanges 6 and 7 into English:

NI shi Wèi Shàoxiào ba?

Aren’t you Major Weiss?

You are Major Weiss, aren’t you? You must be Major Weiss.

Nèi shi Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn? Isn’t that the Ambassador Hotel?

That is the Ambassador Hotel, isn’t it?

That must be the Ambassador Hotel.

Each translation reflects a different degree of certainty on the part of the speaker. (While the differences in certainty are expressed in English by variation in wording, they can be expressed in Chinese by intonation.) You will probably find that the ’’isn't it”/”aren't you” translation fits most situations.

The short answer shide is an expanded form of the short answer shi, with the same meaning": ”Yes, that's so.” Shìde is also the word used for the "yes” in the military "Yes, sir.”

Nà (nèi); In the subject position, nà (nèi), "that," and zhè (zhèi). "this," may be used either as free words or as bound words, with -ge following. Compare:

|

Nà |

shi Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn. | |

|

(That |

is the Ambassador Hotel.) | |

|

Nà |

-ge |

shi Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn. |

|

(That |

one |

is the Ambassador Hotel.) |

|

However, the question form nS- (nèi-) Nàge (fàndiàn) shi Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn?

gōngzuò ma?

|

is a bound word. Which one (hotel) is the Ambassador Hotel? Where does your friend work now? He works in Tainan. Where do you work? I work at the defense attache’s office. Where do you work? I work at a bank. Does your friend work in Taipei? He doesn't work in Taipei; he works in Taichung. |

Notes on Nos. 8-11

Wǔguānchù, ’’defense attache’s office," literally means "military attache's office."

Zài...gōngzuò: Compare these two sentences:

|

Tā |

zài |

Táinán. | |

|

(He |

is in |

Tainan.) | |

|

Tā |

zài |

Táinán |

gōngzuò. |

|

(He |

in |

Tainan |

works.) |

The sentence Tā zài Táinán gōngzuò seems to have two verbs: zài, "to be in/at/on," and gōngzuò, "to work." But there is only one verb in the translation: "He works in Tainan." The translation reflects the fact that zài loses its full verb status in this sentence and plays a role like that of the English preposition "in." The zài phrase in Chinese, like the "in" phrase in English, gives more information about the main verb gōngzuò; that is, it tells where the action takes place. "He works," and the work takes place "in Tainan." In sentences like this, the word zài is a prepositional verb. Most relationships expressed by prepositions in English are expressed by prepositional verbs in Chinese.