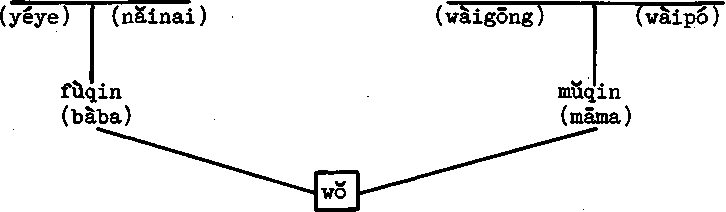

wǒ

érzi xífu

(son daughter-in-law)

STANDARD CHINESE: A MODULAR APPROACH

OPTIONAL MODULE: CUSTOMS SURROUNDING MARRIAGE, BIRTH AND DEATH

Before starting the MBD Module, you should have at least completed the Arranging a Meeting Module.

August 1979

Copyright (c) 1980 by Lucille A. Barale, John H. T. Harvey and Thomas E. Madden

PREFACE

Standard. Chinese: A Modular Approach originated in an interagency conference held at the Foreign Service Institute in August 1973 to address the need generally felt in the U.S. Government language training community for improving and updating Chinese materials to reflect current usage in Taipei and in Peking.

The conference resolved to develop materials which were flexible enough in form and content to meet the requirements of a wide range of government agencies and academic institutions.

A Project Board was established consisting of representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency Language Learning Center, the Defense Language Institute, the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute, the Cryptologic School of the National Security Agency, and the U.S. Office of Education, later joined by the Canadian Forces Foreign Language School. The representatives have included Arthur T. McNeill, John Hopkins, and John Boag (CIA); Colonel John F. Elder, III, Joseph C. Hutchinson, Ivy Gibian, and Major Bernard Muller-Thym (DLl); James R. Frith and John B. Ratliff, III (FSl); Kazuo Shitama (NSA); Richard T. Thompson and Julia Petrov (OE); and Lieutenant Colonel George Kozoriz (CFFLS).

The Project Board set up the Chinese Core Curriculum Project in 197^ in space provided at the Foreign Service Institute. Each of the six U.S. and Canadian government agencies provided funds and other assistance.

Gerard P. Kok was appointed project coordinator, and a planning council was formed consisting of Mr. Kok, Frances Li of the Defense Language Institute, Patricia O’Connor of the University of Texas, Earl M. Rickerson of the Language Learning Center, and James Wrenn of Brown University. In the Fall of 1977 > Lucille A. Barale was appointed deputy project coordinator. David W. Dellinger of the Language Learning Center and Charles R. Sheehan of the Foreign Service Institute also served on the planning council and contributed material to the project. The planning council drew up the original overall design for the materials and met regularly to review their development.

Writers for the first half of the materials were John H. T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry, who worked in close cooperation with the planning council and with the Chinese staff of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Harvey developed the instructional formats of the comprehension and production self-study materials, and also designed the communicationbased classroom activities and wrote the teacher’s guides. Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry wrote the tape scripts and the student text. By 1978 Thomas E. Madden and Susan C. Pola had joined the staff. Led by Ms. Barale they have worked as a team to produce the materials subsequent to Module 6.

All Chinese language material was prepared, or selected, by Chuan 0. Chao, Ying-chi Chen, Hsiao-jung Chi, Eva Diao, Jan Hu, Tsung-mi Li, and Yunhui C. Yang, assisted for part of the time by Chieh-fang Ou Lee, Ying-ming Chen, and Joseph Yu Hsu Wang. Anna Affholder, Mei-li Chen, and Henry Khuo helped in the preparation of a preliminary corpus of dialogues.

Administrative assistance was provided at various times by Vincent Basciano, Lisa A. Bowden, Beth Broomell, Jill W. Ellis, Donna Fong, Judith J. Kieda, Renee T. C. Liang, Thomas Madden, Susan C. Pola, and Kathleen Strype.

The production of tape recordings was directed by Jose M. Ramirez of the Foreign Service Institute Recording Studio. The Chinese script was voiced by Ms. Chao, Ms. Chen, Mr. Chen, Ms. Diao, Ms. Hu, Mr. Khuo, Mr. Li, and Ms. Yang. The English script was read by Ms. Barale, Ms. Barry, Mr. Basciano, Ms. Ellis, Ms. Pola, and Ms. Strype.

The graphics were produced by John McClelland of the Foreign Service Institute Audio-Visual staff, under the general supervision of Joseph A. Sadote, Chief of Audio-Visual.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach was field-tested with the cooperation of Brown University, the Defense Language Institute, the Foreign Service Institute, the Language Learning Center, the United States Air Force Academy, the University of Illinois, and the University of Virginia.

The Defense Language Institute printed the preliminary materials used for field testing and has likewise printed this edition.

CONTENTS

UNIT 3 Part I

APPENDIX Unit Vocabulary Characters

OBJECTIVES

General

The purpose of the Module on Customs Surrounding Marriage, Birth and Death is to furnish you with the linguistic skills and cultural background information you need to take part in conversations about changing attitudes and practices with regard to courtship, marriage, birth, divorce, death and funerals in China, and to conduct yourself in a culturally appropriate manner when you come in contact with Chinese people at the time of one of these significant events in their lives.

Before starting the MBD module, you should have at least completed the Arranging a Meeting Module. You may, of course, use this module at any later point in the course.

Specific

When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

1. Ask about the age when most people get married.

2. Ask about how a wedding is celebrated and what differences there are in marriage practices between the city and the country.

3. Ask about the current local customs regarding gifts for weddings, births, and funerals.

U. Ask about the frequency of divorce.

5. Talk about the functions and statuses of the people who play a role in arranging a present-day traditional marriage.

6. Ask questions about the bride, the groom, and the ceremony in a modern-day wedding.

7. Ask about population control efforts, changes in population control policy, restrictions on young people having children, what factors are taken into consideration in family planning, and how old most couples are when they have children.

8. Congratulate a new mother. Ask about a new-born infant’s health, appetite, and weight, and describe the baby in terms of traditional values.

9. Talk about the traditional beliefs and practices with regard to the mother’s health before and after giving birth.

10. Present condolences to someone whose relative has died, comfort and

express concern for that person.

11. Ask, after deciding if appropriate, about the circumstances of the death and the funeral.

12. Apologize for not being able to attend a funeral.

13. Ask what attire and behavior are appropriate when attending a funeral.

. Customs Surrounding Marriage, Birth, and Death: Unit 1

PART I

1. Zhōngguo zhèngfǔ shì hu shi tíchàng niánqìng rén wan jiéhūn?

2. Zhèngfǔ tíchàng wǎnliàn wǎnhūn.

3. Nèige qíngnián, gōngzuò hen nǔlì.

4. Nóngcūn nianqìng rén yě shíxíng wǎnhūn ma?

5. Wǎnhūn yǐjīng chéngle yìzhong fēngqì.

6. Xiǎo LǏ he tǎ liàn’ài hen jiǔ le, kǎshi yìzhí hu yào jiéhūn.

7. Zhège xiǎo chéngshì ke piào-liang le!

Does the Chinese government advocate that young people marry late?

The government advocates late involvement and late marriage.

That young person is very hardworking

Do the young people in the countryside also practice late marriage?

Late marriage has already become a common practice for young people.

Xiǎo Lì has been in love with her for a long time, but he’s never wanted to get married.

Boy, is this little town pretty!

NOTES ON PART I

Notes on No. 1

tíchàng: ’to advocate, to promote, to initiate, to recommend, to encourage’

Zhè shi shéi tíchàngde? Who advocates this?

nianqìng: ’to be young’ (literally, ’years-light’ or ’years-green’. There are two different characters with the same sound used for the second syllable.)

Tā zhènme niánqìng, zhènme She’s so young and so beautiful!

piàoliang!

Wǒ niánqīngde shíhou, bù When I was young, I didn’t like

xǐhuan kàn shū. to read.

Zhèixiē niǎnqing rén dōu ài These young people all love to go

kǎn diànyīng. to the movies.

Nèige niǎnqīngde Zhōngguo That young Chinese person speaks

rén, Yīngwén shuōde bú cuò. pretty good English.

jiéhūn: ’to get married’, also pronounced jiēhūn. Notice that in Chinese you talk of ’getting married', while in English we talk of 'being married'. And it follows grammatically that jiehūn is a process Verb, not a state verb. Jiéhūn will always be seen with an aspect marker such as le or will be negated with méi.

Tāmen jiéhūnle méiyou? Have they gotten married yet? (This

is the equivalent of 'Are they married?)

Nǐ jiéhūn duo jiǔ le? How long have you been married?

Jiéhūn is a verb-object compound, literally meaning 'to knot marriage*. Jié and hūn can be separated by aspect markers, such as de or guo.

Nǐ shi shénme shíhou jiéde hūn? When did you get married? or Nǐ shi shénme shíhou jiéhūnde?

Wang Xiānsheng jiéguo sāncì Mr. Wang has been married three

hūn. times.

To say 'get married to someone' use the pattern gēn ... jiéhūn.

Tā gēn shéi jiéhūn le?

To whom did he get married?

Note on No. 2

wǎnliàn wǎnhūn: 'late involvement and late marriage'. Wǎnliàn is an abbreviation for wan liàn’ài, 'mature love*, (liàn’ài means 'romantic love, courtship'), and wǎnhūn is an abbreviation for wan jiéhūn, 'late marriage'. This policy has been promoted since the 19éOs, but only actively enforced since the 1970s. It is difficult to-generalize about the required minimum marriage ages, as they differ from city to city and might be nonexistant in certain rural and national minority areas, where the government is trying to increase the population. The minimum age has been progressively raised over the years, until 1978 when the rules were eased a bit. In general, if the combined ages of the couple exceeds fifty years (or the female's age exceeds the male's), then the marriage is allowable.

Note on No, 3

qīngnián: ’youth, young person’. Do not confuse this noun with the adjectival verb niánqīng, ’to be young’. (See Notes on No. 1)

Zhèiwèi qīngnián lǎoshī yīnggǎi This young teacher should go to a dào dàxué qù jiao shū. university to teach.

In this sentence, the noun qīngnián is used to modify the noun lǎoshī, ’teacher’.

A: Wo jìde sānshiniǎn yīqiǎn I remember that thirty years ago nǐ tèbié ài chī tang. you especially loved to eat candy.

B: Shi a, nèi shíhou women dōu Yes. Back then we were all young háishi qīngnián. Xiǎnzài people. Now I’m old, and my

lǎo le, yá bù xíng le. teeth aren’t good any more.

nulì: ’to be hardworking, to be diligent’, or as an adverb, ’diligently, hard*.

Tā suīrán hen null, kěshi tāde Although he’s very hardworking, his Yīngwen háishi bù xíng. English is still not good enough.

Wo děi null xué Zhōngwén. I have to study•Chinese very hard.

nóngcūn: ’rural areas,

Nóngcūnde kōngqì bǐ chéngli hǎoduō le.

Tāmen jiā zǎi nóngcūn zhù.

countryside, village

shíxíng: ’to practice, to carry out

Nī zhèige jìhua hěn hǎo, keshi wo xiǎng bù neng shíxíng.

Zhèige banfa yǐjīng shíxíngle sānge xīngqīle, kěshi jieguǒ bù hǎo.

The air in the country is much better than in the city.

Their family lives in the country.

(a method, policy, plan, reform)’.

This plan of yours is very good, but I don’t think it can be carried out

This method has been in practice for three weeks, but the results aren’t good.

Notes on No. 5

cheng: ’to constitute, to make, to become’.

Tāde xuéxí yìzhí hen hǎo, bìyè yǐhòu ānpai gōngzuò bù chēng went!.

W V X. x

Wode nuer xianzai chengle jiějie, tā zhēn xǐhuan tāde xiǎo mèimei.

fēngqì: ’established practice,

Xiànzài you bù shǎo qìngniǎn bú yào zài shāngdiànli mài dōngxi, zhèizhōng fēngqì zhēn bù hǎo.

Xiànzài zài Zhōngguo, you yǒule niàn shūde fēngqì.

His studies have been good all along, so after he graduates, setting up a job for him won’t constitute a problem.

My daughter has become an older sister. She really likes her little sister.

custom; general mood’.

There are a lot of young people now who don’t want to sell things in shops. This practice is really bad.

Now in China there is again a general atmosphere of study.

Notes on No. 6

he: ’with’. You have seen he used between two nouns or pronouns as a conjunction meaning ’and’. Here you see it used as a prepositional verb meaning ’with’. The word gēn, which you have seen, also has both meanings, ’and* and ’with’.

Formerly, gēn was the most frequently used word for ’with’ or ’and’ in the Mandarin spoken in North China, and he was more often written. But he has come into wide conversational use in pùtōnghuà. In addition to this variation, school children in Taiwan are sometimes taught to say hàn instead of he, which is the same character with another pronunciation.

Generally speaking, if you use he or gēn you should not have any problem being understood by any speaker of Standard Chinese.

liàn’ài: ’to fall in love, to be in love; romantic love, courtship’. This is the socially acceptable way to describe a romantic relationship between two people. Notice that liàn’ài can be used both as noun and as a verb. (Liàn’ài is written with an apostrophe to show where the syllable division is: liàn ài, not lià nài.)

Tāmen liàn’àile hǎojiniǎn le. They’ve been in love for quite a few years now.

Tāmen xiànzài kāishī liàn’ài le. They’ve just started to fall in love.

Wōmende liàn’ài zhī you sāntiān, Our love is only three days old and jiu bù xíng le. already it’s over.

The noun liàn’ài is often used in the phrase tǎn liàn’ài, ’to be romantically involved’ or more literally ’to talk of love’.

Tāmen liǎngge tan liàn’ài yǐjīng The two of them have been in love for

tánle hen jiǔ le.

quite a while now.

Wo méiyou he tā tan liàn’ài.

I’m not in love with her.

In China young people tend to go out in groups. When two people are seen going out alone, then it is assumed that they have serious intentions for the future.

Notes on No. 7

kě: ’really, certainly*. This is an adverb which intensifies state verbs. Kě can be used before a negative.

Tāmen liǎngge kě hǎo le’. The two of them are very good friends.

Kě bú shi ma’. Isn’t that so! (Really! or No kidding!)

Nà kě bù xíng! That really won’t do!

Nà kě bú shi yíjiàn hǎo shi. That’s really not a good thing.

Nǐ kě yào xiǎoxīn! You’ve got to be careful!

Although some Chinese are fond of using the word kě, to other Chinese it may sound too full of local color with which they do not identify.

Peking:

An American exchange student talks in their late twenties.

A: Wo jìde shàngcì nǐ shuō nǐ

èrshibásuì le, hái méiyou j iéhūn.

B: Duì.

A: Wǒ yìzhí xiǎng wènwen ni,

Zhōngguo niánqīng rén hǎoxiàng sānshisuì zuǒyòu cái jiéhūn, shì bu shi?

B: Duì le. Women qīngnián you

hen duō shì yào zuò. Yào nǔlì gōngzuò, nǔlì xuéxí, bū yào zǎo jiēhūn! Zhèngfù yě tíchàng wǎnliàn wǎnhūn. Zài chéngshì-li niánqīng rén dōu zài èrshi-wǔliùsuì yihòu cái Jiēhūn.

with her language teacher. They are both

A: Nóngcūnlǐde niánqīng rén yě

shíxíng wǎnhūn ma?

B: Duì, tāmen yě shíxíng wǎnhūn.

Zài nóngcūn, wǎn liàn’ài wǎn jiēhūn yǐjīng chéngle yìzhǒng xīn fēngqì. Wǒ you yíge zài Běijīng jiǎoqū gōngzuòde péngyou xià lībài jiēhūn, nǐ yào bu yao hé wo yìqī qù kàn-kan? Wǒ gěi ni ānpai yixiar.

A: Hǎojíle. Nà kě zhēn you

yìsi, gang dào zhèr jiù you zhènme yíge hǎo jīhui.

I remember last time you told me that you’re twenty-eight years old and you’re not married yet.

Right.

I’ve been meaning to ask you all along, it seems as if young people in China don’t get married until they’re about thirty, is that so?

Right. We young people have a lot of things we have to do. We have to work hard and study hard; we shouldn’t get married early.’ The government also promotes late involvement and late marriage. In the city, young people don’t get married before the age of twenty-five or twenty-six.

Do the young people in the rural areas practice late marriage too?

Yes, they do too. In the rural areas, late involvement and late marriage have already become a new common practice. I have a friend who works in the suburbs of Peking who’s getting married next week. Do you want to go see it with me? I’ll arrange it for you.

Great. That would really be interesting. And such a good opportunity so soon after getting here.

NOTE ON THE DIALOGUE

...zài èrshiwǔliùsuì yǐhòu cái jiēhūn: This is quite a change from Imperial times, when females might be married off at age thirteen and males at age six so as to insure the family fortunes or fend off economic difficulties later. Nontheless, regulations are less strict in the countryside today, where one can marry perhaps at age twenty.

PART II

8. Xiànzài Zhōngguo rén jiēhǔn you shénme yíshì?

9. A: Nī jiehūn de shíhou nǐde qīnqi sònggei ni shénme lǐwù?

B: Tāmen sònggei wo yìxiē xiǎo lǐwù zuò jìniàn.

10. A: Xùduō nan qīngniàn jiehūn yǐhòu zhùdao nūj iār qu.

A: Zhè gēn yīqiānde fēngsú you hen dàde qūbié.

B: Kě bu shi ma*. Zhēnshi gǎi-biànle bù shǎo.

11. fírqiě zài nongcūn yě shíxíng wǎnhūn.

What kind of ceremony do the Chinese have when they get married now?

What gifts did your relatives give you when you got married?

They gave me a few small presents as mementos.

Many young men now go and live with the wife’s family after they get married.

This is very different from the customs of the past.

I’ll say! It’s really changed a lot.

Furthermore, late marriage is also practiced in rural areas.

NOTES ON PART II

Notes on No. 8

yíshì: ’ceremony, function’ This can be used to refer to a range of different ceremonies, from the signing of a treaty or agreement to the taking of marital vows.

In old China, marriages were celebrated extravagantly. It was not uncommon to find families going into debt because of the joyous occasion, which marked a new generation added to the family line. This elaborate ritual served to strengthen familial bonds and the newlyweds’ feeling of obligation owed to the family.

In PRC cities of today, lack Of extra money and coupons to purchase food for guests, celebration space, and free time for preparation limit the celebration often to procedural formality alone—registration with the local police bureau. Wedding dinners may still be enjoyed in the countryside, where there are fewer restrictions on time and food.

Notes on No. 9

qīnqi: ’relatives’ Qīnqi is slightly different from the English word ’relatives’ in that it does not include one’s immediate family, that is parents or children, but is used to refer to all other relatives. (One’s immediate family are called jiāli ren.)

Nīmen jiā qīnqi duō ma? Do you have a lot of relatives

in your family?

Women jiā qīnqi kě duo le! We have lots of relatives in

our family.

sònggei; ’give (a gift) to ...’ The verb song has several meanings. One is ’to send’, as in Wo bǎ nīde xíngli sòngshangqu le, ’I sent your luggage upstairs.’ Another is to give someone something as a present.

Here you see sòng with the prepositional verb gěi ’for, to’ after it. You have also seen jiāogei, ’to hand over to ..., to submit to...’. When gěi is used after the main verb as a prepositional verb, it must be followed by the indirect object, that is, the person or thing to whom something is given. Gěi can also be used this way with jì ’to send’, and mài ’to sell’.

Wo bǎ zhèijiǎn yīfu jìgei wǒ I sent this piece of clothing to my mèimei le. younger sister.

Tā bǎ fǎngzi mǎigei wǒ le. He sold his house to me.

In these examples the direct object, clothing or house, is up front in the sentence, making it necessary to use gěi to put the indirect object after the main verb. This usually happens in sentences where the object is specific and the bǎ construction is preferred. When song is followed by an indirect object, however, the gěi is usually optional.

Wo yào song ta yíge xiǎo līwù. I am going to give him a small present.

Wǒ yào sònggei ta yíge xiǎo I am going to give him a small present,

līwù.

...sònggei ni shénme līwù?: Wedding gifts for friends and relatives in the PRC are generally ’’useful” items. Common among these are nuǎnpíng, hot water jugs; huāpíng, vases; tǎidēng, table lamps; bī, pens; liǎnpěn, wash basins; or cǎnjù, kitchen items.

zuò: ’to act as, to serve as’. Tāmen sònggei wo yìxiē xiǎo līwù zuò jìniàn. is literally ’They gave me a few small presents to serve as mementos.’

Zhèige xuéxiào bìyède xuésheng, A lot of students who graduated from hěn duō dōu zuò lǎoshī le. this school have become teachers.

Yòng zhèiběn xīn shū zuò līwù, Would it be okay to use this new hǎo bu hǎo? book as a present?

Zuò, ’to act as, to serve as’ is often seen used with yòng, ’to use’ as in the example above, yòng ..■ zuò ..., ’to use (something) as (something) else’.

jìniàn: ’memento, remembrance; to commemorate’.

Wo gěi ta yìzhāng zhàopiàn zuò I’ll give him a photo as a memento, jìniàn.

Notes on No. 10

xǔduō: ’many; a great deal (of), lots (of)’. Xǔduō is used as a number (it can be followed by a counter) to modify other nouns.

A: Hái you duòshao qián?

B: Hái you xǔduō.

Tā māile xǔduō (zhang) huàr.

How much money is there left?

There’s still a lot left, or There’s a lot more.

He bought a lot of paintings.

Xǔduō. has several things in common with hen duō, in addition to similarity of meaning. Used as modifiers in front of nouns, both xǔduō and hen duō can (1) be used alone, (2) be used with de, and (3) be

followed by a counter, but not usually -ge.

Tā rènshi xǔduō rén.

Tā rènshi hen duō rén.

Tā jiànle xǔduō(de) rén.

Tā jiànle hen duō(de) rén.

Bìchǔli you hen duō (jiàn) dàyī.

He knows a lot of people.

He saw (met with) a lot of people.

There are a lot of overcoats in the closet.

Tā xiěle xǔduō (běn) shū.

He wrote a lot of books.

Hen duō is probably more common than xǔduō. Some speakers feel that they do not use xǔduō in conversation; many speakers, however, do not feel any restriction about using it in conversation.

V

...zhùdao nǔjiār qu: ’to go live with the wife’s family’ You’ve seen the prepositional verb dào used after main verbs, as in nādao loushàng qu, ’take it upstairs’. Following verbs expressing some kind of motion, the use of dào is fairly straightforward. But in the above example from the Reference List, dào is used with a verb which is not usually thought of as expressing motion, zhù, ’to live, to inhabit’. Here is another example of zhù used in a phrase expressing motion:

Tā shi zuotiān zhùjinlaide. He moved in yesterday.

The verbs zhàn ’to stand’ and zuò ’to expressing motion.

Qǐng ni zhàndao nèibianr qu, hǎo bu hǎo?

Qǐng ni zuòdao qiǎnbianr qu, hǎo bu hǎo?

sit’ can also be used in phrases

Would you please go stand over there.

Would you please go sit up front.

Due to the lack of housing, which might involve a wait of from one to three years for newlyweds, it is not infrequent now to find the groom join the household of his new bride. This is in contrast to former tradition, which stated that the woman became part of the man’s family, and of course, moved into his family’s house.

In the past, for the groom to join the household of his new bride carried special significance. It was called rù zhuì and might take place when a family had only female children and the father wanted his daughter’s husband to take his last name in order to carry on the family line.

qūbiě: ’difference’ When expressing the difference between two things, use ... gēn ... you qūbié.

Zhèiběn zìdiǎn gēn nèiběn you hen dàde qūbié.

There is a big difference between this dictionary and that one.

Zhèige xuéxiào gēn nèige xuéxiào you shénme qūbié?

Zhèiliǎngge bànfǎde qūbié zài nǎr?

What is the difference between this school and that one?

What is the difference between these two methods?

Kě bū shi ma*. : ’Yes, indeed’., I’ll say!’, or more literally, ’Isn’t it so’.’ Ke bū shi ma! is often used in northern China to indicate hearty agreement, or to indicate that something makes perfect sense to the speaker, something like English ’Well, of course!’ or ’Really.’’.

bù shǎo: Literally ’not a little’, in other words, ’quite a lot’.

Tā you bù shǎo huà yào gēn ni shuō.

Zài Měiguo bù shǎo rén you qìchē.

érqiě: ’furthermore, moreover’

Jīntiān tiānqi bù hǎo, érqiě hǎoxiàng yào xià xuě.

He has a lot he wants to say to you.

In America a lot of people have cars.

The weather is bad today, and furthermore it looks as if it’s going to snow.

. fírqiě is often used, in the pattern bú. dan.. .érqiě.. ., ’not only... but also...’ or ’not only...moreover...’:

|

Zhèizhǒng huār bú dàn hao kàn, érqiě fēicháng xiāng. |

This kind of flower is not only | |

|

pretty, but it’s alsc |

) very fragrant. | |

|

Wǒ bú dàn ài chī tang, érqiě |

I not only like to eat |

candy, |

|

shénme tian dōngxi dōu ài |

(moreover) I like to |

eat anything |

|

chī. |

sweet. | |

Tā bú dan xuéguo Zhōngwén,

érqiě xuéde bú cuò.

Wo bu dan méiyou hé tā tan liàn’ài, érqiě wo yě bú dà xǐhuan ta.

Not only has he studied Chinese, but moreover he has learned it quite well.

Not only am I not in love with her, moreover I don’t like her very much.

Peking:

The American exchange student and her language teacher continue their conversation:

A: Zhōngguo rén jiéhūnde shíhou

you shénmeyàngde yíshì?

B: Méiyou shénme yíshì, jiù shi qīng qīnqi péngyou lai he diǎnr chá, chī diǎnr tǎng, diǎnxin, shenmede.

A: Qīnqi péngyou song hu song

līwù?

B: Yǒude rén song yìdiǎnr xiǎo

līwù zuò jìniàn.

A: vWo tīngshuō yīqián nóngcūnli nūhǎizi jiéhūnde shíhou, nǎnjiā yào song xǔduō līwù. Zhèige fēngsǔ shì hu shi yě gǎihiàn le?

B: Shì a! Zhèizhǒng shìqing

zài bù shǎo dìqū dōu méiyou le. Érqiě xiànzài yě yǒude nan qīngnián jiēhūn yīhòu zhùdao nujiǎr qu. Zhèi gēn yīqiánde fēngsǔ yě you hen dàde qūbié.

A: Kě bǔ shì ma! Zhēn shi gǎibiànle bù shǎo.

What kind of ceremony is there when the Chinese get married?

There is no ceremony, we just invite friends and relatives to come and have some tea, candy, snacks, and so on.

Do the friends and relatives give gifts?

Some people give small gifts as a memento.

I’ve heard that it used to be that in the country, when a girl got married, the man’s family would have to give a lot of gifts. Has this custom changed too?

Yes! In many regions, this kind of thing doesn’t exist any more. Furthermore, now there are also young men who go to live with the wife’s family after they get married. This is also very different from the customs of the past.

I’ll say! It has really changed a lot.

PART III

12. Nǐmen jiéhūn yǐqiǎn shuāngfāng dōu hen liǎojiě ma?

13. Xiànzài Zhōngguo líhūnde bú tài duō.

1U. Nèiduì fūfù hú zài yíge dìqū gōngzuò.

15. Tā měiniǎn you duōshǎo tiānde tànqǐnjià?

16. Fūfù zǒngshi nénggòu zài yìqǐ bǐjiào hǎo.

17. A: Tāmen shi. jǐngguo xiāngdāng-de kǎolū yǐhōu cǎi jié-hūnde.

A: Dànshi hù zhīdào wèishénme, tāmen hāishi you hen duō wèntí.

18. Nānnū yǐngdāng bǐcǐ liǎojiě yǐhòu zài jiéhūn.

19 • Nǐ xiǎng tā huì bu hui bang -wǒ jiějué zhèige wèntí?

Before you were married, did you both know each other very well?

There aren’t many people getting divorced in China now.

That married couple doesn’t work in the same region.

How many days of leave does he get every year to visit family?

It’s always better if married couples can be together.

They gave it quite a bit of consideration before they got married.

But for some reason or other they still had a lot of problems.

A man and woman should know each other well before they get married.

Do you think he will help me solve this problem?

NOTES ON PART III

shuāngfāng: ’both sides, both parties’

Zhèijiàn shìqing shi Zhōngguo This matter is known to both hé Měiguo shuāngfāng dōu America and China,

zhīdaode.

bǐcǐ: ’the one and the other; each other, mutually’

Suīrān women méiyou shuō huà, Although we didn’t say anything, we kěshi bǐcǐ dōu zhīdao, both knew. There was nothing

tāde bìng méiyou bànfa le. that could be done for his illness.

Yǒude dàxuéshēng xǐhuan zài bìyède shíhou bǐcǐ song lǐwù.

A: Zhōumò hǎo!

B: Bǐcǐ, bǐcǐ!

liǎojiě: 'to understand; to acquaint oneself with,

Some college students like to give each other gifts when graduating.

Have a nice weekend!

You too!

to try to understand’

Zhèijiàn shi, wo bù dong, hǎi děi qù liǎojiě yíxià.

Wǒ liǎojiě ta.

Tā juéde tǎ méiyou yíge péngyou zhēnde liǎojiě tā.

Notice that when you want to say ’to someone’, the Chinese word to use is to have made someone’s acquaintance).

I don’t understand this, I have to go back and try to understand it again.

I understand her.

He feels that he doesn't have a single friend who really knows him.

know someone' meaning 'to understand liǎojiě, not rènshi (which simply means

Note on No. 13

... líhūnde bú tài duō: 'There aren't many people getting divorced ... Líhūnde, 'those (people) who get divorced', is a noun phrase in which líhūn is nominalized by -de.

Notes on No. 1U

fūfù: 'husband and wife, married couple'.

Tāmen fūfù liǎngge dōu fēicháng hǎo.

Those two (that couple) are both

very nice.

bú zài yíge dìqū gōngzuò: 'do not work in the same region*. Yíge, 'one', is frequently used to mean 'one and the same'. Here are some more examples:

Women dōu zài yíge xuéxiào niàn shū.

Tāmen liǎngge dōu shi yíge lǎoshī jiāochulaide.

All of us go to the same school.

They are both the product of the same teacher.

Note on No. 15

tànqīnjià; 'leave for visiting family'. Tàn qǐn means to visit one's

closest relatives, usually parents

Míngtiān tā jiù qù Shanghai tan qīn le.

Mote on No. 16

zǒngshi: ’always, all the t ime *•

Tā zǒngshi āi qù Huáměi kāfēitīng.

nénggōu: ’can, to be able to’.

a spouse, or children.

Tomorrow he’s going to Shanghai to visit his family.

This adverb may also occur as zǒng.

He always loves to go to the Huáměi Coffeehouse.

This is a synonym of néng.

Notes on No. 17

Jīngguo: ’to pass by or through, to go through’. Jīngguo can mean 1) to pass by or through something physically, or 2) to go through an experience.

Jīngguo zhèicì xuéxí yīhòu wo kě qīngchu duō le.

As a result of this study, I see things a lot more clearly.

Wǒ měitiān xià bān huí jiāde Every day on my way home from work

shíhou, dōu jīngguo Bǎihuō I pass by the Bǎihuō Dàlóu.

Dālóu ...dōu

jīngguo Bǎihuō Dālǒu.)

Nǐ jīngguo zhèige wūzide When you passed by this room,

shíhou, nǐ méiyou kànjian didn’t you see us working inside?

women zài lǐtou gōngzuō ma?

xiāngdāng: ’quite, pretty (good, etc.); considerable, a considerable degree of’.

Tāde shēntǐ xiāngdāng hǎo. His health is quite good.

kǎolu: ’to consider; consideration’.

Wǒ yǐjīng kǎolùguō le, tā I have already given it consideration

háishi yīnggāi shàng dàxué. he should still go to college.

danshi: ’but’, a synonym of kěshi.

Wǒ yǐjīng qùguo le, dànshi I already went there, but I didn’t

wo méiyou kàndao ta. see her.

Notes on No. 18

nannū: ’male and female’.

Nánnūde shìqing zuì nan shuō. Matters between men and women are the hardest to judge.

yīngdāng: 'should, ought to'. Yīngdāng is a less-frequently heard word for yīnggāi. These two words share in common the following meanings:

(1) ’should’ in the sense of obligation or duty.

Zánmen shi tongzhì, yīngdāng We two are comrades, we should help (or yīnggāi) bīcī bāngmáng. each other.

(2) ’ought to' in the sense of 'it would be suitable to'.

Wàitou lěng, nǐ yīnggāi (or It's cold out, you should put on

yīngdāng) duō chuān yìdiǎnr. some more clothing.

(3) 'should* in the sense of 'it would be desirable to'.

Nǐ yīnggāi (or yīngdāng) You should try this, it’s fun.

shìyishi, zhēn hao wánr.

(U) 'should' in the sense of 'it is expected'.

Shídiān zhōng le, tā yīnggāi It's ten o'clock, he should be here (or yīngdāng) kuài dào le. soon.

Tā xué Zhōngwén xuéle sānnián He's been studying Chinese for three le, yīnggāi xuéde bú cuò le. years, he should be pretty good

by now.

bǐjiào: 'relatively, comparatively, by comparison'. Also pronounced

Jīntiān bījiāo rè.

Zhèijiàn yīfu gǎile yǐhòu, bǐjiào hǎo yìdiǎnr.

Zhèi liǎngtiān tā bǐjiào shūfu yìdiǎnr, bù zěnme fā shāo le.

It's hotter today.

After this article of clothing is altered, it will be better.

The past couple of days he's been feeling better, he doesn't have such a high fever any more.

You may sometimes hear Chinese speakers use bǐjiào before other adverbial expressions like bú tài 'not too', bu zěnme 'not so', bú nàme 'not so' or hen 'very'. Careful speakers, however, feel that bǐjiào should not be used in such cases.

Notes on No. 19

huì: ’will; might; be likely to’. The auxiliary verb huì is used to express likelihood here.

Míngtiān tā huì bu hui lái? Will he come tomorrow?

Wo qù bǎ men guānhǎo, nǐ huì If I go close the door, will you

bu hui juéde tài rè? feel too hot?

jiějué: ’to solve, to settle (a problem), to overcome (a difficulty)*.

Nǐ bú yào jí, qiánde wèntí Don’t get anxious, the problem of

yǐjīng jiějué le. money has already been solved.

Washington, D. C.

A graduate student in Chinese studies from Peking.

A: Women rènshi zhǐ you liǎngge

duō xīngqī, kěshi yǐjīng shi lǎo péngyou le.

B: Duì. Women tiantiān zài

yíkuàir, zhēn hǎoxiàng shi lǎo péngyou le.

A: Wǒ yìzhí xiǎng wènwen ni nǐ

shi shénme shíhour jiéhūnde ne?

B: ō! Wǒ shi qiǎnniǎn jiehūnde.

A: Nǐ èrshibǎsuì le. Nǐ àiren

ne?

B: Tā sānshièr le.

A: Nǐmen jiéhūnde shíhou kě bù

xiǎo le! Zhōngguo niánqīng rén dōu shi zhèige yàngzi ma?

B: Duì le. Zhèngfǔ tíchàng wǎn-

liàn wǎnhūn. Nianqīng rén yě dōu yào nǔlì xuéxí, nǔlì gōng-zuò, bū yào zǎo jiēhūn.

w

A: Chengshili nude duo da

jiéhūn?

B: Chàbuduō èrshiwǔsuì zuǒyòu.

A: Nǎnde ne?

B: Dàgài èrshibāsuì zuǒyòu.

A: Jiéhūnde shíhour you shénme-

yàngde yíshì?

B: Méiyou shénme yíshì. Būguò jiēhūn nèitiān qǐng qīnqi péngyou lai hēhe chǎ, chī diǎnr tǎng, diǎnxin shenmede. Yě you rén song dianr xiǎo lǐwu zuò

talks with an exchange student

We’ve only known each other for two weeks or so, but we’re old friends already.

Yes. We’re together every day; it really is as if we’re old friends.

I’ve been meaning to ask you all along when you were married.

Oh. I was married the year before last.

You’re twenty-eight years old. How about your spouse?

He’s thirty-two.

You certainly weren’t young when you were married! Is it this way for all Chinese young people?

Yes. The government promotes late involvement and late marriage. Also, all young people should study hard and work hard, and shouldn't get married early.

At what age do most women get married in the cities?

After about twenty-five.

And men?

After about twenty-eight.

What kind of ceremony is there when someone gets married?

There is no ceremony. But on the day of the marriage relatives and friends are invited to come and drink tea, eat a little candy, snacks and so forth. Some people also give a

jìniàn.

A: Nongcūnlīde niǎnqǐng rén yě

shíxíng wǎnhūn ma?

B: Duì. Zài néngcūnli wǎn

liàn’ài wǎn jiehūn ye yǐjīng chéngle yìzhǒng fēngqì.

A: Néngcūnli nūhǎizi jiéhūnde

shíhou nǎnjia hǎi yào song xúduō lǐwù ma?

B: Bú yào le. Érqiě xiànzài you.

xiē nǎn qīngniǎn jiéhūn yǐhòu hǎi zhùdao nūjiār qu. Zhè gēn yǐqiǎnde fēngsú you hen dàde qubié.

A: Kě bú shi ma! Zhēn shi

gǎibiànle bù shǎo.

Xiànzài Zhōngguo líhūnde duo bu duo?

B: You, kěshi bǐjiǎo shǎo.v

Yīnwei jiēhūn yǐqiǎn nǎnnū shuāngfǎng bǐcǐ bǐjiǎo liǎojiě, yòu jīngguo xiāngdāngde kǎolū, suéyi líhūnde bú tài duō.

A: Wo tīngshuō Zhōngguo you

yìxiē fūfù bú zài yíge dìqū gōngzuò, bú zhùzai yíge dìfang, zhè huì bu hui you wèntí ne?

B: Fūfù bú zài yíge dìfang

gōngzuò, suīrǎn měiniǎn you bànge yuède tànqīnjià, dànshi hǎi you hěn duō bù fǎngbiàn. Suéyi wèile ràng tamen gèng hǎode gōngzuò hé xuéxí, yīng-dāng bang tamen jiějué zhèige wèntí.

A: Duìjíle. Fūfù zongshi nénggòu zài yìqǐ bījiào hǎo.

small gift as a memento.

Do the young people in rural areas also practice late marriage?

Yes. Late involvement and late marriage have already become a common practice in the rural areas.

In the farm villages does the family of the husband still have to give a lot of presents when a girl gets married?

Not any more. Furthermore now , there are even young men who live with the wife’s family after they get married. This is very different "from the customs of the past.

I’ll say! It’s really changed a lot.

Are there many people who get divorced in China now?

Yes, there are, but relatively few. The man and the woman know each other rather well before they get married, and they give the matter quite a bit of consideration, so not too many people get divorced.

I hear there are some couples in China who don’t work in the same place. Do problems ever come about because of this?

If the husband and wife don’t work in the same place, even though they get half a month’s leave every year to visit family members, it’s still very inconvenient. So in order to let them work and study even better, we should help them solve this problem.

You’re so right. It’s always better if the husband and wife can be together.

NOTES ON THE DIALOGUE

...nanjia hái yào song xǔduō lǐwù ma?: In traditional China, the groom’s family gave gifts to the "bride’s family to compensate for the loss of their daughter. (For the loss of the daughter might also entail a substantial loss of property and servants.) In Taiwan, it is still the man’s family who in most cases pays for the wedding arrangements. In the PRC today, these customs no longer exist.

Xiànzài Zhōngguō líhūnde duō bu duō?: Although allowed by law with the mutual consent of both parties, it is not easy to obtain a divorce in the PRC. With the exceptions of one party being either politically questionable or terminally ill, the majority of couples are asked to resolve their differences via study and group criticism.

...you yìxiē fūfù bú zài yíge dìfang gōngzuò: Many couples still have to be split up in order for each to have work. (Jobs are arranged for and assigned by the local government.) This is, of course, a great hardship since it is improbable that either will be able to arrange a transfer of job to the other’s work-place. The splits are arranged in order to increase rural population and provide labor for rural jobs. The partner left in the city, usually the woman, can go to the countryside to join her spouse, but rural life is so difficult that this is not likely.

...suīrán měinián you bànge yuède tànqǐnjià: There are two types of leave for visiting one’s family in the PRC. One is for unmarried children to return home to see their parents, the other is for couples who are assigned to different places for work. These trips are paid for by one’s work unit (but communes have no family leave provisions). If the person on leave is working relatively near his home, he is allowed a fifteen day visit once per year and a worker who is located relatively far from home can take a thirty day visit once every two years.

|

Vocabulary | |

|

bīcī |

each other, mutually; you too, the same to you |

|

bījiào (bījiǎo) |

relatively, comparatively; fairly, rather |

|

bǔ dan bù shǎo |

not only quite a lot, quite a few |

|

chéng chéngshì |

to become, to constitute, to make city |

|

dǎnshi |

but |

|

érqiě |

furthermore |

|

fēngqì fēngsǔ fūfù |

common practice; general mood custom married couple, husband and wife |

|

gǎibiǎn |

to change |

|

he huì |

with; and might, to be likely to, will |

|

j iéhūn (j i ēhūn) jiejué jīngguo jìniàn kǎolū kě kě bú shì ma! |

to get married to solve to go through, to pass by or through memento, memorial to consider; consideration indeed, really I’ll say, yes indeed, that’s for sure |

|

liàn’ài |

to be romantically involved with; love |

|

liǎojiě (liáojie) líhūn līwù (līwu) |

to understand; understanding to get divorced gift, present |

|

nánjiā(r) nǎnnu nénggòu niánqīng nongcūn nūjiā(r) nǔlì |

the husband’s family male and female can, to be able to to be young rural area, countryside the wife’s family to be hardworking, to be diligent; diligently, hard |

|

qīngnián qīnqi qūbié |

youth, young person relatives difference, distinction |

|

shíxíng |

to practice, to carry out (a method, policy, plan, ‘reform, etc.) |

|

shuāngfāng sòng |

both sides, both parties to give (something as a gift) |

|

tan qīn tànqīn |

to visit family to visit relatives (usually means |

|

tànqīnjià tíchàng |

immediate family) leave for visiting family to advocate, to promote, to initiate |

|

wǎnliàn wǎnhūn |

late involvement and late marriage |

|

xiāngdāng xuduō |

quite, pretty, very many; a great deal (of), a lot (of) |

|

yīngdāng yíshì yìzhí |

should, ought to ceremony all along, all the time (up until a certain point) |

|

zhèngfǔ zhùdao zǒngshi zuò |

government to move to, to go live at always to serve as, to act as; as |

Customs Surrounding

Marriage, Birth, and Death: Unit 2

PART I

1. Hòutiān shi nǐmen xiáojie dàxǐde rìzi.

2. Xīnláng zài Taiwan Yínháng gōngzuò, rén hen lǎoshi, yě hen shàngjìn.

3. Women Xiùyún gēn tā j iāowǎng yǐjīng yìniánduō le, duì tā hen mǎnyì.

U. A: Nǐmen gen nánfāngde fùmǔ shóu bu shóu?

B: Bú tài shóu. Kěshi zāo jiù tīngshuōguo.

B: Tāmen yì lai tíqīn women jiù dāying le.

5. A: Tāmen tánlái tānqù tánle hen jiǔ bù néng juédìng.

A: Kěshi hòulái háishi wǒ gào-su tamen yīnggāi zěnme bàn.

The day after tomorrow is your daughter’s wedding day.

The bridegroom works at the Bank of Taiwan. He’s very honest and very ambitious.

Our Xiùyún has been seeing him for over a year now, and she’s very pleased with him.

Did you know the groom’s parents very well before?

Not too well. But we’d heard of them long before.

As soon as they came to propose the marriage we agreed to it.

They talked and talked for a long time and couldn’t decide.

But later it was I who told them what they should do, after all.

6. Wǒ nuérde hūnlī zài Éméi Canting jùxíng.

7. Tīngshuō jiéhūn lǐfú shi xīnniāng zìjǐ zuòde, tā zhēn nénggàn.

8. Wǒ zhù yīyuànde shíhou nǐmen hāi song huā lai, ài, zhēn shi tài xièxie le.

My daughter’s wedding will be held at the Omei Restaurant.

I hear that the wedding gown was made by the bride herself. She’s really capable.

When I was in the hospital you even sent flowers. Thanks so much.

NOTES ON PART I

Notes on No. 1

xiáojie: ’daughter’. You have seen xiáojie meanirfg ’Miss’ or ’young lady’. Here it is used to mean ’daughter’. Note, however, that it is used only in referring to someone else’s daughter, not in referring to one’s own daughter(s).

Tā you jǐwèi xiáojie? How many daughters does he have?

Nǐmen xiáojie zhēn piàoliang. Your daughter is really pretty.

Xiáojie, meaning either ’Miss’ or ’daughter’, is not in current usage in the PRC.

dà xǐde rìzi: ’wedding day’, literally ’big joyful day’. Xǐ ’to be glad, Joyful', is used in several expressions having to do with weddings. The character for xǐ is often used as a decoration. For weddings, two xǐ characters together are used as a decoration.

Notes on No. 2

ren hen lǎoshi: ’he's very honest'. Ren, 'person', can be used to refer to a person's character. It can be used with a noun or pronoun before it, for example Tā ren hen lǎoshi, literally 'As for him, his person is very honest'. The wording Tā ren ... is often used to talk about the way someone truly is:

Tā rén hěn āi'bāngzhu bié rén. He (is the sort of person who) likes to help others.

Liu Xiānsheng rén hěn tebié, Mr. Liu is a different sort of shénme shìqing dōu yào wen person, he has to ask 'why' about

yige wèishenme. everything.

Tā rén hěn kèqi. He's a very polite sort of person.

Sometimes rén refers to a person's mental state of being:

Wǒ hēde tài duō, rén hái you I had too much to drink and I'm still diǎnr bu qīngchu. a little foggy.

Ren also sometimes refers to a person's physical self. This meaning is mostly used in situations where a contrast is implied, something like 'And

as for the person himself, ...’. For

Wǒ yìzhí zhǐshi he tā tong diànhuà, jīntiān zāoshang, cái dìyīcì jiàn miàn, tā ren fēicháng piàoliāng.

Tāmen jiehūn bu dào yíge yuè, xiānsheng jiù dào Jiāzhōu niàn shū qu le, rén zài Měiguo, xīn zài Táiwān, shū zěnme niàndehǎo ne?

example:

All along I had only talked to her over the phone, but this morning I met her for the first time. She's very beautiful.

They hadn’t even been married for one month when her husband went to California to go to school. He was in America, but his heart was in Taiwan, how could he possibly study well?

Notes on No. 3

jiāowāng: ’to associate with, to boyfriend-girlfriend relationships.

Wǒ he tā méiyou shénme tèbiéde jiāowāng.

have dealings with’, often said of

There’s no special relationship between him and me. (Said by a daughter in explanation to her mother.)

In the PRC jiāowāng is not used this way; use rènshi, ’to know (a person)’ or jiāo péngyou, ’to make friends’ instead. In the PRC, you will hear jiāowāng used in phrases such as "lǐangguo rénmínde jiāowāng”, ’the contact (association) between the peoples of these two countries*.

Notes on No. U

nánfāng: ’’the bridegroom’s side”, a phrase which often refers to the bridegroom himself, and sometimes refers to the bridegroom’s family, relatives, and friends collectively. Nanfāng, "the bridegroom’s side", happens to be a homonym of nánfāng, ’the South’.

Zhōngguo rén jiéhūnde shíhou, When Chinese get married, the groom’s nánfāng dà qǐng kè. family hosts a big feast.

Jiéhūn yǐqián nánfāng nūfāng Before a marriage, the groom’s side bicǐ song lí. and the bride’s side give each

other gifts.

LNūfāng means "the bride’s side, referring either to "the bride" herself, or to ’the bride’s family, relatives, and friends collectively’.]

shou: ’to be familiar with ...’ Also pronounced shu. Shou is used with hé for people and with duì for places.

Wǒ hé tā hen shou. I know him very well.

Tā duì Táiběi hěn shóu. She knows Taipei very well.

Shóu also means ’to be cooked sufficiently' and ’to be ripe*.

zǎo: You’ve learned this as the verb ’to be early’, now you see it used to mean ’long ago’.

Wǒ zǎo zhīdào nǐ bù huílai. I knew long ago that you wouldn’t

come back.

Wǒ zǎo tīngshuō le. I heard about it long ago.

Zǎo is usually followed by jiù to stress the idea of ’as early as that’.

Wǒ zǎo jiù gàosu tā nèijiàn shi le.

I told him that long ago. (Said to correct an impression that he didn’t actually know it so early.)

Wǒ zǎo jiù xiǎng lai kàn ni, yìzhí méi shíjiān.

I’ve been meaning to come see you for a long time, but I never had the time.

tíqǐn: ’to bring up a proposal of marriage’ Traditionally, the man’s parents would visit the parents of the woman they wished their son to marry in order to bring up the subject of marriage. The situation in Taiwan is changing rapidly today, but some marriages are still proposed in this way. More frequently, however, the children simply inform their parents of their own arrangement.

dāying: ’to agree (to something),

Tā dāying gěi wo nèijiàn dōngxi, zěnme tā xiànzài you bù gěi le?

Nǐ dāying ta le, dāngrǎn yīnggāi péi ta qù.

Nǐ dāying zuòde shi, yídìng yào zuodào.

Nǐ dāyinglede shi, wèishénme bú zuǒ?

to consent, to promise’

He agreed to give me that thing. How is that now he won’t give it to me?

You promised him, of course you should go with him.

You must do what you promise to do.

Why don’t you do this thing that you have promised?

Nǐ dāyingguode shi, Jiù yīnggāi zuòdào.

Wǒ méi dāying gěi ni yíge hùzhào.

You ought to do things that you promise.

I didn’t promise to give you a passport.

Dāyjng can also mean ’to answer’.

Tā Jiao ni, nī zěnme méi dāying? He called you, how come you didn’t answer?

Notes on No. 5

tánlai tánqù: ’to talk over’.

|

Tánlai tánqù, yě bùnéng jiějué zhèige wèntí. |

We discussed it for a long time, but still couldn’t solve the problem. |

|

Tánlai tánqù, tánde hěn you yìsi. |

It got very interesting, conversing back and forth. |

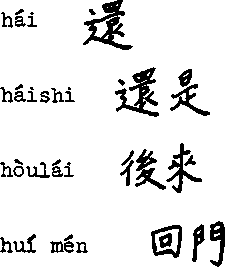

juédìng: ’to decide’.

|

Wo juédìng yào qù. |

I’ve decided that I’m going. |

|

Wo yǐjīng juédìng jiù zhènme ban. |

I’ve already decided that it’ll be this way. |

|

W3 hái méi juédìng gāi zěnme ban. |

I haven’t yet decided what should be done. |

Notice that when you want to say ’I can’t decide whether (to do something)’ or ’I haven’t decided whether (to do something)’, the object of juédìng is a choice-type question.

Wǒ hái méi Juédìng qù bu qù.

I haven’t yet decided whether to go or not.

Wǒ bù néng juédìng wǒ qù bu qù.

W3 hěn nán juédìng rang bu ràng ta qù.

Wǒ shi bu shi gāi huíqu, hěn nan juédìng.

I can’t decide whether to go or not.

I’m having a hard time deciding whether to let him to or not.

It’s hard to decide whether or not I should go back.

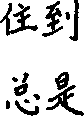

hòulái: ’afterwards, later *. You have already learned another word

which can be translated as "afterwards” or ’’later": yǐhòu. Yǐhòu and hòulái are both nouns which express time. Here is a brief comparison of them.

(1) Yǐhòu can either follow another element ’in which case it is translated as "after ...’’) or it can be used by itself.

Tā láile yǐhòu, women jiù zou After he came, we left, le.

Yǐhòu, tā méiyou zāi láiguo. Afterwards, he never came back again.

Hòulái can only be used by itself.

Hòulái, tā shuì jiao le. Afterwards, he went to sleep.

(2) Both yǐhòu and hòulái may be used to refer to the past. (For example, in the reference list sentence, yǐhòu may be substituted for hòulái. But if you want to say ’’afterwards" or "later" referring to the future, you can only use yǐhòu. When it refers to the future time, yǐhòu can be translated in various ways, depending on the context:

Yǐhòude shìqing, děng yǐhòu zài shuō.

Let’s wait until the future to see about future matters.

Yǐhòu nǐ you kòng, qīng cháng lái wán.

Wǒ yǐhòu zài gàosu ni.

Tāde háizi shuōle, yǐhòu tā yào gēn yíge Rìben rén jiehūn.

Usage Note: Yǐhòu has the meaning some past event functions as a dividing boundary, and yǐhòu refers to the period from the end up to another point of reference (usually the time of usage it is often translated as "since".

In the future when you have the time, please come over more often.

I'll tell you later on.

His child said that someday, he wants to marry a Japanese.

of "after that". It can imply that point in time, as a sort of time

of that time boundary speaking). In this

Tā zhǐ xiěle yìběn shū, yǐhòu He only wrote one book, and hasn't zài méi xieguo. written any since.

Ránhòu stresses the succession of one event upon the completion of a prior event.

Wǒ shàngwū zhǐ you liǎngjié I have only two classes in the

kè, ránhòu jiù méi shì le, morning, and after that I don't women kéyi chuqū wánr. have anything else to do, so we

háishi: 'in the end, after all' You have seen háishi meaning 'still', that is, that something remains the same way as it was. Here háishi is used to mean that the speaker feels that, all things considered, something is the case after all.

Háishi tā duì.

He is right, after all.

Note on No. 6

jūxíng: 'to hold (a meeting, banquet, celebration, ceremony, etc.)' For this example you need to know that diǎnlǐ means 'ceremony'.

Míngtiān jǔxíng hìyè diǎnlǐ. Tomorrow the graduation ceremony-

will he held.

Notes on No. 8

hái: ’even, (to go) so far as to’ You have seen hái meaning ’still’"as in Nǐ hái zài zhèr!., ’You’re still here.’’. You’ve also seen hái meaning ’also, additionally’, as in Wǒ hái yào mǎi yǐpíng qǐshuǐ., ’I also want to huy a hottie of soda.’ Here you see hái meaning additionally in the sense of additional effort. The sentence Nǐmen hái song huār lai, hái expresses the speaker’s feeling that sending flowers went heyond what was expected or necessary.

zhēn shi tài xièxie le: ’I really thank you so much.’’ You have seen tài used to mean ’very, extremely’, as in Tài hǎo le!, ’Wonderful!’. Notice that here it is used with xièxie.

Taipei:

A woman goes to visit her old friend her daughter and future son-in-law.

A: Gōngxǐ, gōngxǐ! Zhège Xīng-

qītiān jiù shi nǐmen èr xiáo-jiede dàxǐde rìzi! Zhèli shi sònggei xīnláng xīnniángde lǐwù.

B: Xièxie! Xièxie! Nǐ tài

kèqi le.

A: Yìdiǎn xiǎo yìsi. Nǐ yídìng

hen mǎng ha! Hūnlǐ dōu zhǔnbèi-hǎo le meiyou?

B: Zuì mǎngde shíhou yǐjīng guò

le, xiànzài chàbuduō dōu zhǔn-bèihǎo le.

A: Xīnlǎng shi nǎli rén a? Zài

nǎli gōngzuò?

B: Xīnlǎng shi Héběi rén, zài Tǎiwān Yínhǎng gōngzuò. Tā rén hen lǎoshi, ye hen shàngjìn.

A: Xiùyun gēn tā shi biéren

jièshào rènshide háishi zìjī rènshide?

B: Shi Xiùyunde lǎoshī jièshàode.

Xiùyun gēn tā jiāowāng dào xiànzài yǐjīng liǎngniǎn le, duì ta hen mǎnyì.

A: Nīmen gēn nǎnfāngde fùmǔ

yǐqiǎn shéu bu shéu?

B: Bù shéu, keshi women zǎo jiù

tīngshuōguo tamen le. Tāmen liǎngwèi dōu zài TǎiDà jiāo shū. Tāmen yì lǎi tíqīn women jiù dāying le.

A: Wǒ kànjian qǐngtiēshang xiězhe

hūnlǐ zài Guōbīn Dàfàndiàn jǔxíng. Nàli dìfang you dà you piàoliang. Zhēn hǎo.

and to present her with a gift for

Congratulations! This Sunday is your second daughter’s big day! Here’s a present for the bride and groom.

Thank you! That’s so nice of you.

It’s just a little something. You must be busy! Is everything all ready for the wedding?

The busiest time has already passed; almost everything is ready now.

Where is the groom’s family from? Where does he work?

The groom’s family is from Hopei. He works at the Bank of Taiwan. He’s very honest and ambitious.

Were Xiuyun and he introduced by someone else or did they meet by themselves?

They were introduced by Xiuyun’s teacher. Xiuyun and he have been seeing each other for two years now, and she’s very pleased with him.

Did you know the groom’s parents well before?

No, but we had heard of them long before. They both teach at Taiwan University. As soon as they came to propose the marriage, we agreed to it.

I saw on the invitation that the wedding is being held at the Ambassador Hotel. It’s very spacious and beautiful there. That’s great.

B: Shi a! Women gēn nǎnfāngde

fùmǔ tánlái tǎnqù tánle hǎo jiu, bù zhīdào zài náli juxíng hūnlī zuì hǎo. Hòulǎi hǎishi wǒ juēdìng zai Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn jǔxíng.

A: Ng! Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn bù zhī

shi dìfang piàoliang, nàlide cài ye tebiě hǎo.

B: Duì le.

A: Xīnniǎngde jiěhūn līfú zài

nǎli mǎide?

B: Bú shi mǎide, shi Xiùyún zìjī

zuòde.

A: Nǐmen èr xiǎojie zhēn nènggàn.

Tiān bù zǎo le, wo gǎi zǒu le.

B: Nǐ hǎi zìjī song līwù lai, zhēn

shi xièxie! Xīngqītiān yídìng lǎi, ǎ!

Yes. We discussed it back and forth for a long time with his parents. We didn’t know where it would be best to hold the wedding. Afterwards I was the one who decided that we would have it at the Ambassador Hotel.

Oh! Not only is the Ambassador Hotel a beautiful place, but the food there is especially good too.

That * s right.

Where did you buy the bride’s wedding gown?

It isn’t bought. Xiuyun made it herself.

Your second daughter sure is capable.

It’s getting late, I ought to be going.

You even brought the gifts yourself. Thank you so much. Be sure to come on Sunday!

NOTES ON THE DIALOGUE

Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn bù zhī shi dìfang piàoliang, nàlide cài yě tèbie hǎo. Traditional wedding foods included huāshēng, peanuts; liǎnzǐ, lotus seeds; and zǎozi, dates, all of which symbolize fertility in that shēng(zī) means ’’give birth to’’ (a son); liǎnzǐ sounds like part of the phrase liǎnshēng guìzī, ’’have sons consecutively”; and zǎozi sounds like part of zǎoshēng guì-zǐ, ’’have an early son.” The wedding marked the beginning of that generation’s carrying on of the family line. Today few adhere to these symbols and food is served according to family preference.

Bú shi mǎide, shi Xiùyún. zìjǐ zuòde: Wedding gowns in Taiwan these days are frequently hand-made or tailor-made, as tailoring is affordable and the quality of work surpasses that of ready-made items. Brides may wear two gowns: a white one for the ceremony (which may be in a church nowadays) and a traditional Chinese red one at the celebration.

PART II

9. Xīnláng J iā xìn Jǐdūjiào, fùmǔ xīwàng tāmen zài jiàotáng jiéhūn.

10. Xīnniáng jiā xìn Fó, fùmǔ bū ràng tamen zài jiàotáng jiéhūn.

11. Tāmen yào zài fǎyuàn gōngzhèng j iēhūn ma?

12. Hūnlǐ yǐhòu bādiǎn zhōng rù xí.

13. Zhège wèntí hěn fùzá.

1U. Wǒde yìjian shi děng liǎngge xīngqī women zài tantan.

15• Tāmen qǐng shéi zhènghūn?

16. A: Hūnlǐ yǐhòu tāmen mǎshàng jiù qù dù mìyuè ma?

B: Bù, yào děng hui mén yǐhòu cǎi qù.

17. Hòutiān yídìng lai chī xǐjiǔ!

18.

A: Nǐmen xiáojie hūnlǐshàng jièshaorén shi nǎliǎngwèi a?

B: Yíwèi shi lai zuò méide Lǐ Jiàoshòu.

19.

Nàwèi yóuzhèngjū Jūzhǎng shi women jiā duōniánde lǎo péngyou.

20.

Tandao jiehūn, nī yě yīnggāi kuài diǎn qù zū jiàn jiéhūn līfú.

The family of the bridegroom are Christians and the parents hope they will be married in church.

The family of the bride are Buddhists, and her parents won’t let them be married in church.

Are they going to have a civil marriage in court?

After the wedding ceremony the banquet will start at eight.

This question is very complicated.

My opinion is that we should wait two weeks and talk about it again.

Whom did they ask to witness the marriage?

After the wedding are they going to leave right away to go on their honeymoon?

No, they’re going to wait until after the bride’s first visit to her family before they go.

Be sure to come to the wedding banquet the day after tomorrow.

Who are the two people who are going to be the introducers at your daughter’s wedding?

One is Professor Li who was the go-between.

That postmaster is a friend of our family from many years back.

Speaking of the wedding, you really ought to hurry up and go rent a wedding gown.

NOTES ON PART II

Notes on No. 9

xìn JieLujiao: ’to believe in (Protestant) Christianity* This is one way of saying ’to be a (Protestant) Christian’.

Notes on No. 10

xìn Fo: ’to believe in Buddha’ This is one way of saying ’to be a Buddhist’.

Notes on No. 11

zài fǎyuàn: ’in court’ Zài is the verb ’to be in, at, or on’, in other words ’to be located (someplace). Zài must be followed by a place word or a place phrase. Just what is considered to be a place word or phrase may be difficult for the non-native speaker to figure out. Words which are not considered to be place words or phases must have a locational ending such as -li or -shang added to them. (Nǐ zài chēshang mǎi piào., ’You buy the ticket on the bus.’)

The names of institutions in Chinese are considered to be place words. The phrase ’in court’ does not need a locational ending, zài fǎyuàn. Here are some other words which can function as place words by themselves. Many of these end with syllables such as -shi (shǐ) ’house, apartment’, -Ju ’office, shop’, -diàn ’inn, shop’, -chǎng ’field, open ground’, -ting ’hall, room’, -suǒ ’place, room’, -jiān ’house, rooms’, guan ’public office, hall*.

Jīntiān xiàwu zài bàngōngshì See you at the office this afternoon! j iàn ’.

Zài běnshì you wuge yóuzhèng- There are five post offices in this

|

jú! |

city. | |||

|

Nǐ zài |

cǎiféngdiàn zuòde |

ba? |

You must have had that tailor’s. |

made at a |

|

Nǐ zài |

canting kàndao ta |

le ma? |

Did you see him in the |

dining room? |

|

Other words |

which behave in a |

similar |

way are: |

|

càishichǎng |

maíket |

fùjìn |

area |

|

cèsuǒ |

toilet |

fuwùtǎi |

service desk |

|

dàfàndiàn |

hotel |

Gōngǎnjú |

Bureau of Public Security |

|

shāngdiàn |

store |

gongsī |

company |

|

dàlóu |

building |

gōngyù |

apartment |

dàshiguǎn dìqū fàndiàn fángj iān fànguǎnzi fàntīng fēijichǎng

embassy region restaurant

room restaurant dining room airport

|

gōngyuán |

park |

|

huìkèshì |

reception room |

|

huǒchēzhàn |

railroad station |

|

jǐngchájú |

police station |

|

kāfēitīng |

coffeehouse |

|

lǎojiā |

hometown |

and many more...including proper names of Restaurants, buildings, associations, organizations, etc.

gōngzhèng: 'notarization, government witness'. A gōngzhèng ren is a notary public.

Note on No. 12

rù xí: 'to take one's seat at a banquet', literally 'to enter the mat(ted area)'.

Women kuài diǎnr zhǔnbèi, Let's get ready a little faster,

tāmen liùdiǎn zhōng jiù the banquet starts at 6:00.

yào rù xí le.

Note on No. 13

fùzá: 'to be complicated, to be complex'. Questions, problems, or situations can be fùzá if there are many pieces or factors figuring into the problem. It is also possible to use fùzá to imply that the situation is messy, problem-ridden.

Tāmen jiāde qíngkuàng tài fùzá, wǒ gǎobuqíngchu.

Zhèige wèntí tài fùzá, hen nán shuōqīngchu.

Zhèige jùzi tài fùzá, zuì hǎo bú zhèiyangr xiě.

Their family situation is too complicated, I can't make heads or tails of it. (This sentence has an ambiguity in both languages.)

This question is so complicated, it's very hard to explain it clearly.

This sentence is too complicated, it would be best not to write it this way.

Fùzá can also be used in a complimentary way. (For this example you need to know that slxiǎng means 'thinking, thought'.)

Tāde sìxiǎng hen fùzá. His thinking is very complex.

This sentence might be said of an Einstein. The opposite of fùzá in this case -would be jiǎndān ’to be simple’, as in ’simple-minded’.

Fùzá is also pronounced fùzǎ.

Note on No. 1H

yìjiàn: ’idea, view, opinion, suggestion’.

Gāngcái tā tánle duì zhèiběn shūde yìjian, wǒ juéde duì women hěn you bāngzhu.

He just told us his opinions on this book, and I feel that they’re really helpful to us.

Wo hěn xiǎng zhīdào, zài zhèige wěntíshang, Zhōngguo zhèng-fǔde yìjian shi shénme?

Wǒ xiǎng xiān qù Shanghai, zài dào Wùhàn, nǐde yìjian zěnmeyang?

Wǒde yìjian shi xiān qù Wùhàn, zài dào Shànghǎi qu. Yīnwei zài guS yíge yuè, Wùhàn fěi-chǎng rěle.

I’d very much like to know what the Chinese government's view is on this question.

I’d like to go to Shanghai first and then to Wuhan, what’s your opinion?

My opinion is to first go to Wuhan, then to Shanghai, because after a month, Wuhan will be extremely hot.

Note on No. 15

zhènghūn: ’to witness a marriage*. Witnesses formerly were persons of good reputation and venerable old age. Today, familiarity is most important. The witness makes a brief speech during the ceremony and stamps the marriage certificate with his name seal. He receives no remuneration for this service, but is honored to have been asked.

Notes on No. 16

dù mìyuè: ’to spend one’s honeymoon’. Dù is the verb ’to spend, to pass (something which is an amount of time, like a holiday). Mìyuè is literally ’honey-moon’.

huimen: ’the bride’s first visit to her own family on the third day after the wedding’, literally ’return to the door’. When the newlyweds return home for this first visit, the family of the bride is given a chance to entertain the couple. More friends and relatives are invited and introduced to them. (It is the groom’s family which arranges the marriage ceremony.)

Note on No. 17 .

xījiū: ’wedding banquet’. Notice that in the Reference List sentence the phrase lai chī xījiǔ is translated as ’to come to the wedding banquet’. A more literal translation might be ’come to eat a wedding feast!. The verb chī could also be rendered into English by ’attend* or ’take part’, as in ’Be sure to come take part in the wedding banquet the day after tomorrow’.

Notes on No. 18

hūnlīshàng: ’at the wedding*. Notice that in English you say ’at the wedding’ while in Chinese you say hūnlīshàng, literally ’on the wedding’. -Shang would also be the locative ending to use for ’at the meeting (huìshang).

jièshaorén: ’introducer*. This is one person in the cast of people who play a part in getting two people together in marriage. Originally, the ’’introducer” functioned in much the same way as match-makers - finding a good mate for a friend or relative. Today, most young people find their own mates. The ’’introducers”, however, still have a ceremonial function. They accompany the bride and groom during the ceremony (one for the bride and one for the groom).

zuò méi; ’to act as the go-between for two families, whose children are to be married’. This person arranged the details of the match. He acted as a go-between for the families of the bride and groom, settling points which were usually of a financial nature. Often the zuò méide was also the jièshaorén. Traditionally, the go-between was an older woman who made a profession of it. She was paid for her services in money if the family was wealthy or in the best pork legs if they were poor. Today any adult can act as the go-between, although the practice is becoming less and less common. During the wedding ceremony, the go-between places his stamp on the wedding certificate.

Wǒ gěi ni zuò méi, hǎo bu hǎo? I’ll act as go-between for you, all right?

Zhang Tàitai qīng wo tī tǎde Mrs. Chang asked me to act as go-nūér zuò méi. between for her daughter.

Notes on No. 19

jūzhǎng; ’head of an office or bureau’. Júzhǎng is only used when the Chinese name of the office or bureau ends with the syllable -jú, as in youzhèngjú, ’post office’. You’ve also seen bùzhǎng, ’minister of a bureau* and kēzhǎng, ’section chief*.

duōniǎn: ’many years*. Here are some examples:

Women duōniǎn bú jiàn le. We haven’t seen each other for many

years.

Women zài yìqǐ gōngzuòle duōnián le.

Wǒ zhù zài zhèr duōnián le, kěshi mei tǐngshuōguo zhèige rén.

We’ve Been working together for many years.

I’ve heen living here for many years, but I’ve never heard of this person.

Notes on No. 20

tándao: ’to talk about, to speak of’. This is used to refer to something that was just brought up in conversation. You have seen dào used as a main verb meaning ’to go to, to arrive at’, and as a prepositional verb meaning ’to towards’. Now you see that dào is also used as a verb ending. Literally, it means ’to, up to’, but its translation into English sometimes changes, depending on the meaning of the verb it is used with. When used with tan, ’to talk, to chat’, -dào can be translated as ’about’ or ’of’. Here are some other examples of -dào used with verbs you’ve already studied:

Women gāngcái hái shuōdao nǐ, nǐ jiù lai le.

Jīntiān nǐ gēn ta jiǎngdao wo méiyou?

Wǒ chángchang xiǎngdao wǒde háizi.

We were even talking of you just now, and here you are!

Did you talk about me with him today?

I often think of my child.

Notice that in the Reference List sentence, tándao is used at the beginning of the sentence to introduce a topic, like we use ’speaking of ...' in English. Here are some other examples:

Tándao jiéhūnde shì, wǒ hái děi xiǎngyixiang.

Tándao zěnme xiě Zhōngguo zì, tā bǐ wǒ zhīdaode duō.

When it comes to talking about marriage, I have to think it over.

When we talk about writing Chinese characters, he knows a lot more than I do.

yě: ’really, after all’. You have seen yě meaning ’too, also’. Another common meaning of yě is ’(even though) ... nevertheless, still’. For example:

Wǒ suīrán shi Zhōngguorén wǒ yě huì shuō yìdiǎn Yīngwén.

Although I am Chinese, I can still speak a little English.

A: Zhèige diànyǐng zěnmeyàng?

B: Bu shi hěn hǎo, dànshi yě hái kéyi.

How was the movie?

It wasn’t great, but it was pretty good nevertheless.

Wo suīrān méi dàoguo Tiān Ān Men, yě zài diànshìshang kàn j ianguo.

Although I’ve never been to Tian An Men, I’ve seen it on television.

In addition, yě often is used to contrast the thought expressed in the sentence with another thought. This meaning can be paraphrased something like this:- ”in spite of anything which might be believed to the contrary, indeed what I am saying is true." Sometimes, however, yě is used when there is not much to contrast it with, and means little more than ”we really ought to agree that what I am saying is true.”

There are many different possible ways to translate this yě into English. The following examples are meant to show some of its range of meaning and some of its possible translations.

Xiànzài shíyīdiǎn bàn le, wǒ yě yào shàng kě le, wǒmende wèntí míngtiān zài tan ba!

It’s eleven-thirty. I really have to be going to class. Let’s talk about our question tomorrow, okay?

Zhōngguo rénkǒu tài duō, zhèngfǔ tíchàng wanliàn wǎnhūn yě shi yínggāide.

The population of China is too large, it really is right for the government to promote late marriage and late involvement.

Tāmen wèishénme yào líhūn, wǒ yě bù zhīdào.

A: Nī zěnme hǎi méi bǎ zhèxiē yīfu xīwān?

B: Wǒ yě bú shi nīde yòngren, bāitiān wǒ yě shàng ban, wǒ méiyou zhènme duō shíjiān.

Nǐ xiànzài yě gāi míngbai le ba?

Women liǎngge rènshi yě you jīnián le, nī yīnggāi liǎojiě wo.

Why they wanted to get a divorce, I really don’t know.

How come you still haven’t finished washing these clothes?

I’m not your servant, after all; I work during the day too, and I don’t have all that much time.

Now you (really) ought to. understand, don’t you?

We have known each other for several years, after all; you ought to understand me.

Taipei:

The day before a young couple is to be married, a friend pays a visit to the mother of the bride:

A: Gōngxǐ, gōngxǐ! Míngtiān shi

nǐmen xiáojie dàxǐde rìzi! Xīnláng shi shénme rén a? Tāmen shi zěnme rènshide?

B: Shi péngyou jièshàode.

Nánfāngde fùqin gēn wǒ xiān-sheng zài youzhèngjú shi téngshì, búguò yǐqián bú tài shou. Hòulái lìngwài yíge xìng Lǐde téngshì jiù lai zuò méi, jièshào tamen rènshi. Tāmen jiāowǎng dào xiànzài yě yìnián duō le. Nàge nánháizi xiànzài àrshibāsuì, rén hen lǎoshi, yě hěn shàngjìn. Xiànzài zài Táiwān Yínháng gōngzuò. Tā bàngōngshìlide rén dōu shuō tā nénggàn. Xiùyún duì ta hěn mǎnyì, érqiě Xiùyún yǐjīng èrshisìsuì le, yě dàole gāi jiéhūnde shíhou le, suoyi nánfāng yì lai tíqīn women jiù dāying le.

A: Wǒ kàn qǐngtiēshang shuō

wǔdiān zhōng zài Guobīn Dàfàndiàn jǔxíng hūnlǐ, liùdiǎn zhōng rù xí. Nà dìfang hěn dà, cài yě hěn hǎo, míngtiān yídìng hěn rènao.

B: Tándao jǔxíng hūnlǐ a, yìjian

duō le. Zhēn fùzá. Xian shi liǎngge háizi yào dào fǎyuàn gōngzhèng jiéhūn, kěshi nánfāngde fùmǔ bù dāying. Tāmen xìn Jīdūjiào, yídìng yào dào jiàotáng qù. Women jiā xìn Fo, zěnme kéyi ràng tamen dào jiàotáng qù jǔxíng hūnlǐ ne! Hòulái, liǎngjiā tánlái tánqù, zuìhòu cái juédìng háishi zài Guóbīn Dàfàndiàn

Congratulations! Tomorrow’s your daughter’s big day! Who’s the bridegroom? How did they meet?

They were introduced by friends.

The father of the groom is a colleague of my husband’s at the post office, but they didn’t know each very well before. Afterwards, another colleague by the name of Li camé to act as the go-between and introduced them. They have been seeing each other for over a year now. The young man is twenty-eight years old now. He’s very honest and ambitious. He works at the Bank of Taiwan. The people at his office all say he’s very capable. Xiuyun is very pleased with him, and besides, she’s twenty-four years old; she has reached the time when she should get married. So as soon as his family came to propose the marriage, we agreed to it.

I see it says on the invitation that the ceremony will be held at the Ambassador Hotel at five o’clock, and that the banquet starts at six. It’s a very big place, and the food is very good. It should be very lively tomorrow.

As far as the wedding ceremony is concerned, there were a lot of different opinions. It was really complicated. At first the two children wanted to go to court and have a civil marriage, but the parents of the groom didn’t agree to that. They’re Christians, and insisted on going to a church. Our family is Buddhist; how could we let them go to a church to hold the wedding! Later, our two families discussed it back and

juxíng hūnlǐ.

A: Shi qǐng shénme rén zhènghūn

a?

B: Zhènghūnrén shi Youzhèngjū

Zhang Júzhǎng. Tā gēn nǎnfāngde fùqin shi duōniǎnde lao péngyou, suéyi yì qǐng ta, tā mǎshàng jiu dāying le.

A: You méiyou jièshàorén? Jièshàorén shi shéi ya?

B: Nánfāngde jièshàorén jiù shi lǎi zuò méide nàwèi Lǐ Xiān-sheng. Women zhèhiān jiù qǐngle Zhāng Zǐmíng Jiàoshòu. Tā shi Xiùyun niàn dàxué shíhoude lǎoshī.

A: Xīnniǎngde jiéhūn lǐfú shi zài shénme dìfang zuòde?

B: Bu shi zuòde, shi zūde.

A: Tāmen jiēhūn yǐhòu yào dào

nǎli qù dù mìyuè?

B: Tāmen jìhua yào dào Alǐ Shān

qù wan yíge xīngqī, húguò tāmen jiéhūn yǐhòu bù néng mǎshàng zou, yào děng huí mén yǐhòu cai qù.

A: 0, hǎo hǎo hǎo. Wo xiǎng

nǐmen yídìng hen mǎng. Wo yīnggāi zǒu le.

B: Nǐ name kèqi, hai zìjǐ lai

song līwù lai. Xièxie, xièxie! Míngtiān yídìng lai chī xījiǔ.

A: Hǎo, míngtiān jiàn.

forth, and finally we decided it would be best to hold the wedding at the Ambassador Hotel.

Whom did you ask to witness the marriage?

The witness is Postmaster Zhang. He’s an old friend of many years of the groom’s father, so as soon as we went to ask him, he agreed right away.

Are there any introducers? Who are they?

The introducer for the groom’s side is the Mr. Li who was the go-between. For our side we asked Professor Zhang Ziming. He was a teacher of Xiuyun’s when she was in college.

Where was the bride’s wedding gown made?

It wasn’t (specially) made, it’s rented.

After they’re married, where are they going to spend their honeymoon?

They’re planning to go to Mt. Ali for a week, but they can’t leave right after the wedding. They have to wait until after the bride’s first visit to her new parents’ home before they go.

Oh, okay. Well, you must be very busy, so I should be leaving now.

You’re so polite, you even brought presents over in person. Thank you! Be sure to come to the banquet tomorrow.

Okay, see you tomorrow.

NOTES ON THE DIALOGUE

...liangge háizi yào dào fǎyuàn gōngzhèng .jiéhūn: Traditional wedding ceremonies were held at home or in ancestral halls (not in temples or pagodas). Modern ones are likely to be held in hotels or restaurants, as there is more room and food is then easier to prepare.

Tāmen jìhua yào dào Ālǐ Shān qù: Ālǐ Shān and Rìyuè Tán (Sun-Moon Lake) are the two most popular honeymoon spots on Taiwan. An average honeymoon stay might last one week.

|

Vocabulary | |

|

ài |

(sound of sighing) |

|

dàxǐ dàxǐde rìzi dāying |

great rejoicing wedding day to agree (to something), to consent, |

|

dù dù mìyuè |

to promise to pass to go on a honeymoon, to spend one’s |

|

duōnián |

honeymoon many years |

|

fǎyuàn Fó fùzá (fǔzá) |

court of law Buddha to be complicated |

|

gōngzhèng Jiehūn |

civil marriage |

|

hái háishi hòulái hui men |

even, (to go) so far as to after all later, afterwards the return of the bride to her parents’ home (usually on the third day after the wedding) |

|

hūnlǐ |

wedding |

|

J iàotáng Jiāowǎng |

church to associate with, to have dealings with |

|

Jǐdūj iào Jiéhūn lǐfú Jièshaorén Juédìng Jǔxíng Júzhǎng |

Christianity wedding gown introducer to decide to hold (a meeting, ceremony, etc.) head of an office or bureau (of which the last syllable is jú) |

|

...-lai...-qù |

(indicates repeating the action over and over again) |

|

lǎoshi (lǎoshi) |

to be honest |

|

mǎnyì mìyuè |

to be pleased honeymoon |

|

nánfāng nénggàn |