STANDARD CHINESE: A MODULAR APPROACH

STUDENT TEXT AND WORKBOOK

MODULE 7: SOCIETY

Before starting Unit 1 of this module, you should have completed core modules 1 through 6 and the optional modules Personal Welfare, Restaurant, and Hotel.

May 1981

Copyright © 1980 by John H. T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale, Roberta S. Barry and Thomas E. Madden

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach originated in an interagency conference held at the Foreign Service Institute in August 1973 to address the need generally felt in the U.S. Government language training community for improving and updating Chinese materials to reflect current usage in Beijing and Taipei.

The conference resolved to develop materials which were flexible enough in form and content to meet the requirements of a wide range of government agencies and academic institutions.

A Project Board was established consisting of representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency Language Learning Center, the Defense Language Institute, the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute, the Cryptologic School of the National Security Agency, and the U.S. Office of Education, later joined by the Canadian Forces Foreign Language School. The representatives have included Arthur T. McNeill, John Hopkins, and John Boag (CIA); Colonel John F. Elder III, Joseph C. Hutchinson, Ivy Gibian, and Major Bernard Muller-Thym (DLl); James R. Frith and John B. Ratliff III (FSI); Kazuo Shitama (NSA); Richard T. Thompson and Julia Petrov (OE); and Lieutenant Colonel George Kozoriz (CFFLS).

The Project Board set up the Chinese Core Curriculum Project in 197^-in space provided at the Forign Service Institute. Each of the six U.S. and Canadian government agencies provided funds and other assistance.

Gerard P. Kok was appointed project coordinator, and a planning council was formed consisting of Mr. Kok, Frances Li of the Defense Language Institute, Patricia O’Connor of the University of Texas, Earl M. Rickerson of the Language Learning Center, and James Wrenn of Brown University. In the fall of 1977j Lucille A. Barale was appointed deputy project coordinator. David W. Dellinger of the Language Learning Center and Charles R. Sheehan of the Foreign Service Institute also served on the planning council and contributed material to the project. The planning council drew up the original overall design for the materials and met regularly to review their development.

Writers for the first half of the materials were John H.T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale, and Roberta S. Barry, who worked in close cooperation with the planning council and with the Chinese staff of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Harvey developed the instructional formats of the comprehension and production self-study materials, and also designed the communication-based classroom activities and wrote the teacher’s guides. Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry wrote the tape scripts and the student text. By 1978 Thomas E. Madden and Susan C. Pola had joined the staff. Led by Ms. Barale, they have worked as a team to produce the materials subsequent to Module 6.

All Chinese language material was prepared or selected by Chuan 0. Chao, ying-chi Chen, Hsiao-Jung Chi, Eva Diao, Jan Hu, Tsung-mi Li, and Yunhui C. Yang, assisted for part of the time by Chieh-fang Ou Lee, Ying-ming Chen, and Joseph Yu Hsu Wang. Anna Affholder, Mei-li Chen, and Henry Khuo helped in the preparation of a preliminary corpus of dialogues.

Administrative assistance was provided at various times by Vincent Basciano, Lisa A. Bowden, Jill W. Ellis, Donna Fong, Renee T.C. Liang, Thomas E. Madden, Susan C. Pola, and Kathleen Strype.

The production of tape recordings was directed by Jose M. Ramirez of the Foreign Service Institute Recording Studio. The Chinese script was voiced by Ms. Chao, Ms. Chen, Mr. Chen, Ms. Diao, Ms. Hu, Mr. Khuo, Mr. Li, and Ms. Yang. The English script was read by Ms. Barale, Ms. Barry, Mr. Basciano, Ms. Ellis, Ms. Pola, and Ms. Strype.

The graphics were produced by John McClelland of the Foreign Service Institute Audio-Visual Staff, under the general supervision of Joseph A. Sadote, Chief of Audio-Visual.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach was field-tested with the cooperation of Brown University; the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center; the Foreign Service Institute; the Language Learning Center; the United States Air Force Academy; the University of Illinois; and the University of Virginia.

Colonel Samuel L. Stapleton and Colonel Thomas G. Foster, Commandants of the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center, authorized the DLIFLC support necessary for preparation of this edition of the course materials.

Jannas R. Frith, Chairman

Oninese Core Curriculum Project Board

CONTENTS

Preface

iii

Introduction

Section 1: To the Student................... 1

Objectives for the Society Module

UNIT 1 Travel Plans Introduction

(Verb) de shi...

Phrases with guānyu, "concerning,” ’’about”

The directional ending -lai huì, ’’might,” "be likely to," "will"

The sentence marker -de, "that’s the way the situation is" Review Dialogue

UNIT 2 Equality of the Sexes Introduction

biéde, "other(s)" ___*■ _______ _

yuè lai yuè..., "more and more..."

xiàng, "like"

The adverb jiù, "as soon/early as that"

UNIT 3 Family Values

The verb ending -qilai: the start of an action or condition conglai bù/méi, "never" cái7 "only," before amounts

-zhe showing the manner of an action

The verb ending -dào: —successful reaching/obtaining/finding

—(with verbs of speech) "of," "about"

—successful perceiving (kàndao)

The adverb zài, "anymore” Placement of phrases with dào, "to," "up to," "until" Review Dialogue

UNIT U A Family History Introduction.........................

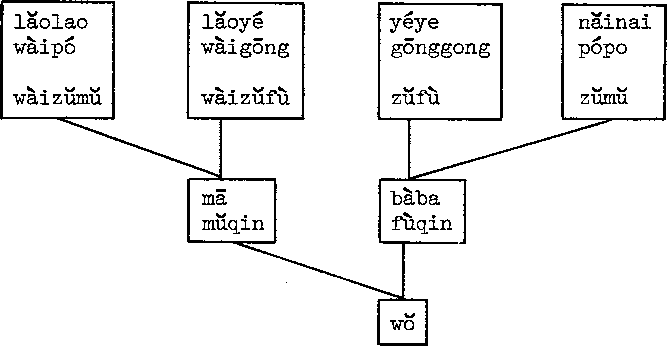

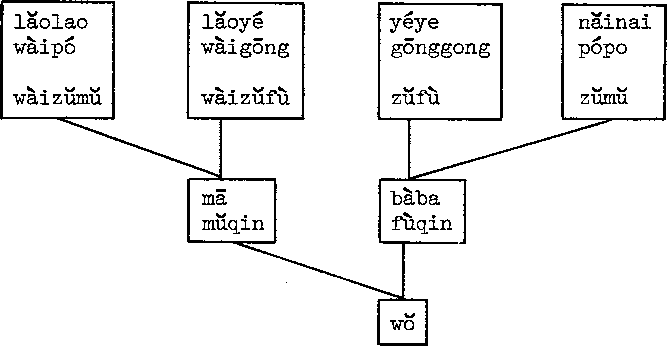

More on ne, marker of absence of change/lack of completion Terms for grandparents

More on indefinite pronouns ("any/no" expressions) bāngzhu and bang máng

Exercise Dialogues ........ ......

UNIT 5 Traditional Attitudes and Modern Changes Introduction . . .

Necessary condition marked by cái

Placement of specifier after a modifying phrase

"In order to"

yǐhòu and hòulái compared Review Dialogue

UNIT 6 Politics and Culture Introduction

-de huà, "if," "in case"

More on -guo vs. -le

Reduplicating adjectival verbs for vividness qù and lai expressing purpose

UNIT 7 Social Problems

Reference Rotes............... 215

-duō le, "much more"

(Verb) (Verb) kàn, "try and. (Verb)"

"Not anymore," "never again" lián...dōu..., "even" zhǐ yào.. , "provided that..."

bú shi... j iù shi... » "if not...then...," "either...or..."

Workbook.......................... . . 23U

UNIT 8 Directions for the Future Introduction

Reference List ................. . .

Action-Process compound verbs

The directional ending -huí

you, "after all," "anyway" yě bu, "don’t even," "won’t even"

Exercise Dialogues .................. .....

SECTION 1: TO THE STUDENT

With the Society module, you are taking a step up to a new level of expression in Chinese. Up till now, you have "been dealing with relatively short sentences about concrete situations. In this module, you will start to encounter longer sentences and more abstract statements. The transition will take some time, but you can make it easier on yourself by developing methodical ways of approaching the new material in each unit. The following suggestions may help.

Keep in mind from here on in that the two skills you will continue to work on, production and comprehension, are no longer expected to stay at approximately the same level. It is natural for your ability to understand what others say to increase more rapidly than your ability to express your own thoughts. As you work through the Society module, bear in mind that, while you are asked to understand all the dialogues, you are required to be able to produce only a limited part of the language you will hear. This is specified in the module objectives, the unit vocabulary lists, and the introductions to the units.

How to Use the Book

Each unit of this book presents quite a bit of new information—much more than anyone can master in a few days’ time. This is because information has also been included simply for comparison or for your future reference. This is what you should master in each unit:

(1) The new grammar listed in the introduction for each unit.

(2) The basic meanings of each vocabulary item. (Related meanings may be given in the reference notes for purposes of comparison, but you are not required to remember them.)

(3) The cultural background information discussed in some reference notes and contained in each unit’s review dialogue.

You may find it helpful to read through the reference notes three times. On the first time through, read only the notes on cultural background. The second time, go through the notes that explain new grammatical structures. The third time, read only the notes on the meanings and usage of new words. For review, test yourself on the example sentences in the notes by covering the Chinese column and trying to translate the English column into Chinese. Check your answer immediately.

How to Use the Tapes

Starting with Module 7, there will be only two thirty-minute tapes per unit, instead of five.

Tape 1 introduces the material on the Reference List, giving you a chance to learn to understand these sentences and to practice saying them. Tape 1 replaces both the C-l and P-1 tapes which you used in Modules 1 through 6.

You will find that the Tape 1 is denser in content and faster paced than either the C-l or P-1 tapes. The number of new vocabulary items in each unit has been increased from 20-25 to 30-35- You will also notice that the sentences have increased in length. Since you must learn to understand as well as say these sentences from a single tape, you may find that you need to rewind the tape and review the presentation of each sentence several times. In addition, explanations which were formerly found on the C-l and P-1 tapes are now found only in the Reference Notes.

Tape 2 replaces the C-2 and P-2 tapes. Each Tape 2 will start off with a review of the sentences from the Reference List. This will be followed by three exercise dialogues. You should listen to each dialogue until you understand it thoroughly. The workbook which accompanies Tape 2 describes the setting of the conversation and provides you with the newvocabulary you need to understand it. (You are not required to learn these additional vocabulary items.) The workbook also contains questions about each dialogue, for which you will need to prepare answers in Chinese. Your teacher will ask you to answer these and other questions about the conversation in class.

When you listen to the recorded dialogues, aim only for comprehension of the ideas. Whether or not you can repeat the sentences word for word is not critical. Since they are in colloquial style, the dialogues sometimes contain phrasing which you are not expected to be able to imitate at this stage, yet with a little effort (it is expected to take repeated listenings), you will understand.

SECTION 2: TO THE TEACHER

The format of the core modules from this point on differs considerably from those preceding, and teaching methods should be adapted to the requirements of this new format. Below are a few suggestions on how to use this and subsequent core modules.

How to Use the Reference Notes

The reference notes in Society include grammatical explanations, discussions of the usage of new words, and some cultural background information. They are called ’’reference’’ notes for a reason: they are here for the student ’s present and future reference. They are not intended as material for classroom study or discussion, for in these later modules, as in the first six, the bulk of classroom time should be spent in the actual use of Chinese. The thoroughness of the notes is intended to relieve you of the need to give lectures on grammar and usage and allow you to devote most of your time with students to live practice of the language. You should familiarize yourself with the content of the notes so that when students pose questions on word usage or a new structure, you can simply refer them to the relevant note.

The copiousness of example sentences in the notes has a double purpose. First, along with the idiomatic English translations, they show the versatility of the vocabulary items they introduce; at. this level of study, a single English translation can seldom fully do justice to the range of nuances expressed by a Chinese word. Second, students can use the example sentences at home for translation practice, either Chinese-English or English-Chinese, using a strip of paper to cover the target-language column and then checking their answer for immediate reinforcement.

How to Use the Exercise Dialogues

The three exercise dialogues in each unit (exercises 2, 3, and H) present completely different situations and characters from the unit review dialogue, but include the same new vocabulary and structures. They provide extra listening comprehension practice at normal conversational speed, an area which should receive increased attention from both student and teacher beginning with this module.

The language of many of the exercise dialogues is very colloquial and thus a change from the style of the preceding modules. At this stage, students must accustom themselves to hearing everyday Chinese, and if given ample practice, their comprehension will improve quickly. But bear in mind that students are not expected to be able to produce sentences in this colloquial style, only to understand them.

The taped exercises 2, 3, and 4, are to be listened to outside of class as many times as is necessary for the student to answer the questions in the workbook section. In class, the teacher should ask the questions, rephrased in Chinese, and have students answer from their notes or, preferably, from

memory. If students bring up questions on colloquialisms contained in the dialogues at this time, handle them quickly; avoid digressions on expressions which are not required for production. The point of this activity is for the students to talk—to practice saying the new words and structures of the unit.

Further Classroom Activities

(1) Use the subjects discussed in the dialogues as points of departure for class discussions in which the teacher takes the part of the Chinese who wants to understand American society and the American students try to explain their ways of thinking and doing things. Depending on class size, the level of the students, and individual students’ competitiveness or reticence, these conversations will need to be more or less structured. If necessary in order to maintain the flow of ideas or to keep a small number of students from dominating the discussion, everyone can be asked to outline possible answers before coming to class, or the teacher may prepare an outline for the students.

(2) Students can be asked to tell the story of the review dialogue or an exercise dialogue in their own words. This can be done by the whole class together; if one student omits an important point in the story, another student can remind him of it or supply it himself.

(3) Have students pick out from the reference list and the dialogues certain sentences which serve a particular communicative function. The Chinese material in this book is especially suited to this type of exercise because of the colloquial tone of the dialogues and the range of emotions and linguistic functions displayed within them. For example, the students may be asked to find a sentence that conveys enthusiasm toward an idea, one that conveys tentativeness when asking a question about a delicate subject, or one that conveys a desire to be helpful. Using the sentences thus found as takeoff points, the teacher can then ask the students to come up with other sentences with the same linguistic function, or ask them to change elements of the sentence to vary its function.

For example, Unit 1 of Society presents some sentences (in the reference list and dialogues) that can be used as responses to proposals:

Wǒ kǎolu kǎolu. I’ll think it over, (non-committal)

Fěicháng hǎo. Great, (enthusiastic)

Na women shuohǎo le . . . Then we’ve agreed . . . (decisive)

Jiù zhèiyang. It’s settled, (decisive)

Students can be asked to add to this list sentences expressing a wider range of responses to a proposal, e.g., flat rejection (Bù xíng!), scandalization (Nà zěnme kěyi a.'), lukewarm acceptance (Kěyǐ ■ . . or Yě hǎo), indecisiveness (M . . . or Nà, wǒ háí děi xiǎngyixiǎng or Zài shuō ba), etc. If you make up supplementary exercises, you may find it effective to base them on the communicative functions of sentences contained in each unit. A list of these functions will be found in each unit’s introduction.

1 !

(M If the teacher and students find that the new grammar needs to be separately discussed in class, such sessions should be confined to a review of the essential new structures, as listed in each unit’s introduction.

Review

The two review tapes consist simply of exercises requiring the students to translate the reference list sentences for Units 1 to U and 5 to 8, respectively. The original order of the sentences in the text has "been scrambled. The first section of each tape is translation from Chinese to English, the second from English to Chinese.

Because material introduced in this module is frequently repeated in subsequent lessons, regular review will not be as important as in the earlier modules, where the situational nature of the lessons means that some vocabulary introduced in order to handle one kind of situation occurs in that one module only. However, if desired, one of each unit’s exercise dialogues can be reserved for review: have students listen to only two instead of all three exercise dialogues while doing the unit, and then return to the third dialogue several units later to brush up on the vocabulary and structures.

Unit 1: SOC 1.1, SOC 1.2 Unit 2: SOC 2.1, SOC 2.2 Unit 3: SOC 3.1, SOC 3.2 Unit U: SOC U.l, SOC k.2 Unit 5= SOC 5.1, SOC 5-2 Unit 6: SOC 6.1, SOC 6.2 Unit 7: SOC 7-1, SOC 7-2 Unit 8: SOC 8.1, SOC 8.2

|

Review Tapes: |

SOC Review |

l-U, |

Tape 1 |

(Chinese |

to |

English) |

|

SOC Review |

1-U, |

Tape 2 |

(English |

to |

Chinese) | |

|

SOC Review |

5-8, |

Tape 1 |

(Chinese |

to |

English) | |

|

SOC Review |

5-8, |

Tape 2 |

(English |

to |

Chinese) |

The Society Module (SOC) will provide you with the linguistic skills and cultural background information you need to visit a Chinese family, discuss some aspects of family life and society, to find out how someone’s fa-mily fits into the pattern of traditional Chinese society, and how it reflects the changes of modern society.

Before starting this module, you must take and pass the MTG Criterion Test. In addition, it is assumed that by this point you will have already completed the optional modules Personal Welfare, Restaurant, and Hotel; vocabulary from these modules is now considered taught.

The SOC Criterion Test will focus largely on this module, but material from the first six core modules and associated resource modules is also included.

OBJECTIVES

Upon successful completion of this module, you should be able to

1. Give the English equivalent for any Chinese sentence in the SOC Reference Lists.

2. Say any Chinese sentence in the SOC Reference Lists when cued with its English equivalent.

3. Ask someone about the size of his family, which family members live at home, and where other family members live and why.

U. Use the rules of Chinese etiquette in social visits: the proper times for visiting; the custom of offering refreshments to visitors and the type of response expected from the visitor; and some polite ways to end a social visit.

5. Discuss the status, duties, and responsibilities of sons in the traditional Chinese family.

6. Discuss the different relationships within the Chinese family, especially those between parents and children, and between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law.

7. Explain why the large (extended) family was the ideal pattern in traditional Chinese society.

8. Use the proper-terms for referring to your own or someone else’s children, and understand the terms for addressing one’s children directly; use the terms for paternal grandparents; use the terms for the parents of one’s friend.

9. Understand why early marriage was a common practice in traditional China.

10. Discuss the effects of the development of industry and business on traditional Chinese society.

11. Discuss the concept of filial obedience.

12. Compare the position of women in Chinese society before and after the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

13. Discuss traditional marriage arrangements in China and the roles women were placed in as a result. Understand the government’s policy toward marriage after 19^9 and the actual changes that have occurred.

1U. Explain and defend some of your personal views on topics such as equality of the sexes, the status of women, living together, marriage, parent-child relationships, care of the elderly, the effects of political and economic conditions on society, crime, and drug abuse.

UNIT 1

Travel Plans

INTRODUCTION

Grammar Topics Covered in This Unit

1. The pattern (Verb) de shi....

2. Phrases with guǎnyu, ’’concerning,” ’’about.”

3. The directional ending -lai.

U. The auxiliary verb huì, ’’might,” ”be likely to,” ’’will."

5. The sentence marker -de, "that’s the way the situation is."

Functional Language Contained in This Unit

1. Offering a visitor something to drink.

2. Responding to an offer of something to drink.

3. Concluding a social visit.

U. Telling someone you can’t take the time to explain something but will talk about it later.

5. Presenting a suggestion or proposal to do something.

6. Responding to a suggestion or proposal to so something.

Unit 1, Reference List

1. A:

B:

2. A:

B:

3. A:

B:

U. A:

B:

5. A:

B:

6. A:

B:

7. A:

B:

Jīntiān wǒ jièdao yìběn hǎo xiǎoshuō.

Shénme xiǎoshuō, rang ni zènme gāoxìng?

Zhǎibǎn xiǎoshuō xiede shi dǎlùde qíngkuǎng.

Guānyu dǎlùde? Jiè gǎí wǒ kǎnkan xíng bu xíng?

Xiǎge xuěqī nǐ xiǎng yánjiū shénme ?

Hai shi lǎo wèntí: Zhōng-guóde zhèngzhi qíngkuǎng.

Zuotiān Xiǎo Ming gei tā nùpéngyou xiě xìn, xiede hǎo chǎng!

Niánqīng rén zǒng shi niánqīng rén. Wo niánqīngde shihou ye shi zhèiyang, nǐ wǎng le?

Shǔj iǎde shihou, nǐ xiǎng dǎo nǎr qu wanrwanr?

Wǒ xiǎng dǎo Yǎzhōu jǐge guojiā qu kǎnkan.

Zěnme, nǐ xiǎng yanjiū Yǎzhōude wénhuǎ chuántǒng?

Bù néng shuō yánjiū. Wǒ zhǐ shi xiǎng qù kǎnkan nǎlide shèhuì qíngkuǎng.

Lǎo Wang, wǒ jīntiān gǎnjué hen bu shūfu.

Kuǎi zuòxia, wǒ qù gei ni

dǎo bēi chá lai.

Today I borrowed a good novel (from someone).

What novel is it that makes you so happy?

This novel is about the situation on the mainland.

About the mainland? How about lending it to me to read?

What are you going to do research on next semester?

It’s still the same old topic: the political situation in China.

Yesterday Xiǎo Ming wrote a letter to his girl friend, and it was really long!

Young people are always young people When I was young I was like that too, have you forgotten?

Where do you want to go over summer vacation?

I’d like to go visit a few countries in Asia-

Oh? Do you want to do research on Asia’s cultural tradition?

It can’t be called research. I just want to go have a look at the social situation there.

Lǎo Wang, I feel awful today.

Sit down and I’ll go pour you a cup of tea.

8. A: NÍ qùde nèige dìfang zhèngzhi, jīngji fàngmiànde qíngxing zěnmeyàng?

B: Jǐjù huà shuōbuq ìngchu, you shíjiān wo zài gen ni mànmànr shuō "ba.

9- A: Yànjiū Zhongguo xiànzàide wèntí yídìng děi dongde Zhongguo lìshǐ.

B: Nǐ shuōde zhèiyidiǎn hen yàojǐn, wo kǎolú kǎolu.

10. A: Nǐ zài Zhongguo zhà liǎng-nián, yídìng huì xuehào Zhōngwénde.

B: Shi a, yìfàngmiàn kéyi xuéhào Zhongwén, yìfàngmiàn yě kéyi duo zhīdao yidiànr Zhōngguode shìqing.

What was the political and economic situation like where you went?

I can’t explain it clearly in just a few sentences; when I have time I’ll tell you all about it.

To study the problems of China now, you have to understand Chinese history.

This point of yours is very important; I’ll think it over.

If you live in China for two years, you’re sure to learn Chinese very well.

Yes, on the one hand I can learn Chinese well, and on the other hand I can find out more things about China.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY

11. yìbiān(r)...yìbiān(r)

12. yímiàn...yímiàn...

doing...while doing...

doing...while doing...

|

VOCABULARY | |

|

cháng chuántǒng |

to be long tradition, traditional |

|

dàlù dào -di an dǒngde |

mainland, continent to pour point to understand, to grasp, to know |

|

-fāngmiàn (-fāngmian) |

aspect, side, area, respect |

|

gǎnjué |

feeling, sensation; to feel, to perceive |

|

guanyu |

as to, with regard to, concerning, about |

|

guójiā |

country, state, nation; national |

|

huì |

might, be likely to, will |

|

jiè jièdao -jù |

to borrow; to lend to successfully borrow sentence; (counter for sentences or utterances, often followed by huà, ’’speech”) |

|

kaolū |

to consider, to think about |

|

mànmānr (manman) |

slowly; gradually, by and by; taking one’s time; in all details |

|

niánqīng |

to be young |

|

qíngkuàng |

situation, circumstances, condition, state of affairs |

|

qíngxing |

situation, circumstances, condition, state of affairs |

|

rang |

to make (someone a certain way) |

|

shèhuì shǔj ià shuōbuqīngchu |

society, social summer vacation can’t explain clearly |

|

wénhuà |

culture |

|

xiǎoshuō (-)xuéqī |

fiction, novel semester, term (of school) |

|

yánjiū (yánjiu, yánjiù) |

to study (in detail), to do research on; research |

|

Yazhōu (Yǎzhōu) |

Asia |

|

yìbiān(r)...yìhiān(r)... yìfāngmiàn..., yìfāngmiàn... |

doing—while doing... on the one hand... , on the other hand; for one thing..., for another...; |

|

yímiàn(r)...yímiànfr)... |

doing...while doing... doing...while doing..• |

|

zhèngzhi zǒng |

politics, political affairs; political always; inevitably, without exception, after all, in any case |

|

zuòxia |

to sit down |

Unit 1, Reference Notes

1. A: Jīntiān wǒ 'jièdao yìběn Today I "borrowed a good

hǎo xiǎoshuō. novel (from someone).

B: Shénme xiǎoshuō, rang ni What novel is it that

zènme gāoxìng? makes you so happy?

Notes on No. 1

jiè: ”to borrow’’ CAlso "to lend," see Notes on No. 2.3

Wo dào túshūguǎn qù jiè shū. I’m going to the library to borrow

Etake out J some books.

For "from," use gēn or xiàng° for people and cong for place names like the library.

Wǒ méi dài qián, xiǎng gēn (xiàng) Níngning qù. jiè.

I didn’t bring any money. I want to go borrow some from Níngning.

Wǒ cóng túshuguǎn jièle yìběn Zhongguo lìshǐ shū.

I borrowed a Chinese history book from the library.

Cong can only be followed by a person if the person is made into a place name, for example by the addition of nèr (nàli):

Wǒ cóng tā nèr jièle wǔkuǎi qián. I borrowed five dollars from him.

For people, you may also use the common pattern wen.. .jiè... , literally "ask.. .borrow.. .

Wǒ wen ta jièle yiběn shū. I borrowed a book from him.

Wǒ bù hǎo yìsi wèn biérén jiè I’m too embarrassed to borrow money

qián. from other people.

jièdao: The ending -dào expresses that the borrowing results in the thing being obtained. You learned -dào and the similar Běijīng -zháo in the verb jiēdao/j iēzhao, "to receive," in the Meeting module.

You need to know not only what the ending -dào means, but also when to use it and when not to. This can’t be summed up in one neat formula, but you will see from the following examples that -dào is used when there was a question of not being able to get the thing. Jiè by itself does not necessarily imply obtaining, so you can use it in situations when you tried to borrow something but couldn’t get it.

I borrowed a dictionary from him.

Wǒ gēn tā jièle yìběn zìdiǎn.

°Xiàng is used more in written style.

Wo qù jièguo, kěshi méi jièdào.

A: Nǐ cóng tūshūguǎn jièdao nèiběn Měiguo lìshǐ shū le ma?

B: Méiyǒu, dōu jièchuqu le. Dàgāi xiā Xīngqīyī cái néng j ièdào.

I went and tried to borrow it, but

I didn’t get it.

Did you get that American history book out of the library?

No, they had all been taken out.

I probably won’t be able to (borrow and) get it until next Monday.

Jiè may have certain other directional or resultative endings. Here are examples.

Zài zhèr kàn kéyi, bù néng jièchuqu.

Tā bǎ wǒde chē jièqu le.

Tā bǎ nèiběn shū jièzǒu le.

Wo cong tā nèr jièlai wūkuài qiān.

You can read it here, but you can’t take it out.

He borrowed my car (and took it away).

He borrowed that book (and took it away).

I borrowed five dollars from him.

rang; "to make" someone a certain way, or "to cause" someone to become a certain way. When used this way, rang is followed by a person and an adjectival verb. You learned rang as "to let" in the Welfare module: Rang wǒ kànkan nǐde hùzhào, "Let me see your passport." ERàng can also mean "to have," "to tell," or "to make" someone do something.J

Tā shuōde huà rang wo hen shēng- What he said made me very angry, qì.

Tā name bú kèqi rang tā péngyou He embarrassed his friend by being hen bù hǎo yìsi. so rude.

Shénme xiǎoshuō?—rang ni zhème gāoxìng;

and the rest of the sentence,

question shénme xiǎoshuō, is like an afterthought.

Zhèi shi shénme kāfēi?—zhème hǎo hē.

Zhèi jiù shi nǐ mǎide chē?— zènme nānkàn!

Nǐ xǐhuan shùxué a?—name méi yìsi!

Compare these

There is a pause after the rang ni zhème gāoxìng, examples:

What kind of coffee is this? It’s so good.

So this is the car you bought? It’s so ugly!

You like math?—such a boring thing!

2. A: Zhèiběn xiǎoshuō xiede shi dalùde qíngkuang.

B: Guānyú dalùde? Jiè gěi wǒ kankan xíng bu xíng?

This novel is about the situation on the mainland.

About the mainland? How about lending it to me to read?

Motes on No. 2

xiě: This verb which you learned as ”to write” is also one of several ways that ’’about” is expressed in Chinese. When used with this meaning, xiě usually appears in the (Verb) de shi construction discussed immediately below.

xiede shi: This structure, (Verb) de shi, is a major structure of Chinese, so pay extra attention.’ Use (Verb) de shi when the verb is not new information and you want to focus instead on the identity of the thing talked about. The pattern itself makes an equational sentence, that is, an A EQUALS B sentence:

|

A |

IS |

B |

|

VERB de |

shi |

B |

|

Tā zuòde |

shi |

bǎicài. |

’’What he’s making is cabbage.”

In sentence 2A, the verb xiě is not new information because any novel must "be written about" something. The object dalùde qíngkuang is new information which is focused on.

A: Nǐ zài Jiǎzhōu Dàxué niànde shi shénme?

B: Wǒ niànde shi jīngjixué.

Zhèige diànyīng jiǎngde shi yige Zhōngguo rén qù Měiguo wande shi.

Gāngcǎi nǐ jiàode shi shénme? Shi fan haishi mian?

Nǐ xiànzài shuōde shi wǒ haishi tā?

Tā hěn xǐhuan kàn shū, kěshi tā kànde dōu shi yìxiē méi yìside xiǎoshuō.

What is it that you study at the University of California?

It’s economics.

This film is about a Chinese going to America to visit.

What did you order just now? Rice or noodles?

Is the person you’re talking about now me or him?

He likes to read, but all he reads are stupid novels.

dàlù: "continent, mainland" Zhōngguo dàlù is "mainland China," which may also be called dàlù for short just as we say "the mainland".

“Other ways are by using the verb jiǎng, "to talk about," as in Zhèiběn shū jiǎng shénme?, "What is this book about?"; and guānyu (see the note in this section).

qíngkuàng: ’’situation, circumstances, state of affairs, condition” Used much more frequently in Chinese than any single one of these translations is used in English. Sometimes the Chinese language uses qíngkuàng when in English we would just say "things" or "the way things are."

Nǐde qíngkuàng gēn tāde chàbuduō.

Wǒ dìdide jīngji qíngkuàng hú tài hǎo.

Nà shi sìshinian qiǎnde shi, xiànzài qíngkuàng hu tong le.

You and he are in about the same situation.

My younger brother’s financial situation isn’t too good.

That was forty years ago. Now things are different.

A: Nǐ něng bu néng gěi wǒ jiǎng- Could you tell me about the way jiang nǐ zài dàlùde qíngkuàng? things were for you on the mainland?

B: Nǐde yìsi shi wǒ zìjīde qíng- Do you mean my own situation? kuàng ma?

Sometimes qíngkuàng means the "picture" about a place (especially an organization); in such cases it may not be necessary to translate it literally.

Tā gěi women jièshaole tāmen He gave us a presentation (briefing) xuéxiàode qíngkuàng. on their school. (E.g., what

grades, how many students and teachers, what subjects are taught, etc. )

Wǒ bú tài shúxī Měidàsīde I’m not too familiar with (the way

qíngkuàng. things are at) the Department of

American and Oceanic Affairs.

guānyu: "with regard to, concerning" The phrase guānyu dàlùde means literally "one concerning the mainland." Guānyu is rather formal. In everyday speech, the idea of "about" is more often expressed in other ways’, but guānyu is often used in formal contexts.

Guānyu is a prepositional verb, which means it is followed by a noun (its object) and is related to the main verb. It is not the best behaved of prepositional verbs, however. Guānyu does not occur where you would normally expect to find a prepositional verb phrase (before the verb, e.g., dào Zhongguo qù). Nor does guānyu occur in a sentence the way "about" does in English. "About" phrases in English are free to occur after the verb, e.g., "talk about Chinese history," "think about your problem." A guānyu phrase (that is, guānyu and its object) can only occur in the following places in the sentence:

Other ways include using the verbs jiǎng and xiě (see Notes on No. 2). For example, if I am watching a T.V. program and you walk into the room and want to ask, "What’s this about?" the most "everyday" way would be Jiǎng shenme de? (actually an abbreviated form of Zhèige jiěmù Eprogram] shi jiǎng shénme de?). It would sound stilted to use guānyu in such an informal situation.You see another example of how "about" is expressed in Chinese on the next page under number (3) in the little dialogue: "About what?" is Shénme diànyǐng?.

(1) Guānyú can occur at the beginning about to be commented on.

Guānyú nèijiàn shi, wo shénme dōu bù zhīdào.

Guānyú nèrde qíngkuàng, ni gěi wo dating dating hāo ba?

Guānyú zhèige, nǐmen hái you méiyou shénme wèntí?

(2) Guānyú can also occur in a phrase

Xièxie ni gàosu wo zhème duō guānyú dàlùde qíngkuàng.

Tā zhīdao hen duō guānyú zhèi-fāngmiànde shìqing.

Women zhèli méiyou duōshao guānyú Zhōngguode shū.

of the sentence to introduce the topic

Concerning that matter, I don’t know anything. (OR I don’t know anything about that matter.)

Would you please ask for me about the situation there?

Do you have any other questions about this?

with -de which modifies a noun.

Thank you for telling me so much about the situation on the mainland.

He knows a lot (of things) about this field. .........

We don’t have very many books about China here.

It also occurs in a phrase with -de, the whole phrase acting as a noun.

Wo cóng Xiao Zhao ner jièlai yi-běn shū, shi guānyú Zhōngguo càide, nǐ kànkan.

I borrowed a book from Xiāo Zhào. It’s (a book) about Chinese food. Have a look at it.

(3) A guānyú phrase (guānyú + noun) viated sentence.

Wo zuotiān kànle yige diànyǐng.

Shénme diànyǐng?

Guānyú Fāguó...

Guānyú Fāguode shénme?

Guānyú Fāguode jīngji.

is occasionally used alone as an abbre-

I saw a movie yesterday.

About what?

About France...

About what (aspect) of France?

About the French economy.

Compare the following English and Chinese sentences. Although the parts in parentheses are optional in English, the Chinese sentences would be considered wrong without the underlined -de phrases. (For the first example you need to know xiāoxi, "news.”)

Nǐ tīngshuō guānyú Tiětuōde xiāoxi ma?

Have you heard (the news) about Tito? (i.e., that he had died)

Bú yào wèn wo guānyú shùxuéde wèntí.

Don’t ask me (any questions) about math.

jiè gěi -wǒ kankan: "lend (it) to me to read" In exchange 1, jiè was translated "borrow." Now you see it used for "to lend." To say "lend something to someone," the gěi phrase always follows the verb jiè.° If the indirect object (person who receives) is a pronoun, gěi may be omitted:

Jiè wo yìzhī bǐ. I

Jiè gěi wo yìzhī bǐ. I Lend me a pen.

(In this extremely common sentence, the gěi is more frequently omitted.)

3. A: Xiàge xuéqǐ nǐ xiǎng What are you going to do

yǎnj iū shénme? research on next semester?

B: Hai shi lǎo wèntí: Zhong- It’s still the same old topic: guóde zhèngzhi qíngkuàng. the political situation in China.

xuéqǐ: "semester, term" Since xuéqǐ means literally just "school-period,’1 it could conceivably apply to a scholastic term of any length, including quarters. Chinese schools, however, run on the semester system (fall-winter and winter-spring).

Xiànzài yěude Měiguo dàxué yíge Some American colleges have semesters xuéqǐ zhǐ you shíèr-sǎnge lǐbài. which last only twelve or thirteen weeks.

Shàngge xuéqǐ nǐ dōu niànle shénme?

What (courses) did you take last semester?

Xuéqí may also be used without the counter -ge: shangxueqi, xiaxuēqi, yixue. qǐ, etc.

yanjiū: "to do research on" a topic (usually at the graduate level or above). Sometimes may be translated as "to study" (in depth, not just pre

paring for a test).

Tā yǎnjiūde shi něifāngmiande wèntí?

Kē Jiàoshòu zài jīngji fāngmian-de yānjiū shi dàjiā hěn shouxīde.

Tāde yanjiū gōngzuò hěn zhòng-yào.

Another meaning is "to look into, ties, opinions, questions):

What area does she study (OR do research on)?

Everyone is familiar with Professor Ke’s research in the area of economics.

His research work is very important.

to consider, to discuss" (possibili-

A gěi phrase before jiè would mean "for," not "to." Example: Tā gěi wo jièle jǐběn shū, "He borrowed a few books for me."

Zhèige wèntí -women děi yánjiū We should discuss (OR look into this) yanjiu. question.

zhèngzhi: ’’politics, political affairs; political"

Keep in mind that because of China’s political system, the word zhèngzhi has a different set of meanings than we are used to. This is a large question which we will not go into in depth here. But to give you an idea of this concept, here is the definition of zhèngzhi from a Chinese dictionary.’

zhèngzhi: The concentrated expression of economics. It comes into being on a particular economic base, serves the economic base, and has a tremendous influence on economic development. In a class society, economic interests are the most fundamental interests of the different classes. In order to safeguard their own interests, the classes inevitably wage intense class struggle among each other. Therefore, class struggle and handling relations between the classes becomes the main content of politics. The relations which politics must handle are the internal relations of a class, relations between the classes, relations between nationalities, and international relations. Politics is manifested in policies and activities in the areas of national life and international relations of political parties, social groups, and social forces which represent certain classes. The politics of the exploiting class has as its aim to oppress the working people and to preserve its own narrow interests. In the politics of the proletariat, bourgeois rule is overthrown with revolutionary violence under the leadership of the proletarian political party, and the dictatorship of the proletariat is established; after power has been seized, socialist revolution is carried through to the end, class struggle is properly waged, and contradictions between ourselves and the enemy as well as contradictions among the people . . . are properly handled; then the focus of struggle is progressively turned towards engaging in the cause of socialist construction and devoting major efforts to developing production, and creating the conditions needed to completely abolish classes and bring about communism.

Note in particular how the politicization of everyday personal relations in the PRC has resulted in zhèngzhi being used in a host of phrases such as "political influence," "political relations," "political background," "political qualifications," etc.

"Cíhǎi, Shanghai Císhū Chūbǎnshè, 1979.

U. A: Zuótiān Xiao Ming gǒi tā nupéngyou xiǒ xìn, xiǒde hǎo cháng!

B: Niánqīng rén zǒngshi niánqīng rén. Wǒ niánqīngde shihou yě shi zhèiyang, nǐ wǎng le?

Notes on No. U

chang: "to he long" opposite of chang is duǎn,

Yesterday Xiǎo Ming wrote a letter to his girl friend, and it was really long!

Young people are always young people; when I was young I was like that too, have you forgotten?

in physical length, or in some cases, "to he short."

time.’ The

Chāngchéng you duo chang? You liùqiānduō gōnglǐ (cháng).

Nǐ xiǒde tai cháng le, duǎn yidiǎnr, hǎo hu hǎo?

Wǒ hen cháng shíjiān méi kǎnjian ta le.

Wo xiǎng nǐ zǎi nǎr zhǎo fángzi yídìng xūyǎo yige hen chángde shíjiān.

Tā zǎi zhèr gōngzuòde shíjiān you duo cháng?

niánqīng: "to he young"

How long is the Great Wall?

It’s over six thousand kilometers (long).

You made this (piece of writing) too long. Could you shorten it?

I haven’t seen him in a long time. (Hen cháng shíjiān is the same as hen jiu)

I’m sure it will take you a long time to find a house there.

How long did he work here?

relative to a particular situation, the teens through the twenties.

Tā niánqīngde shihou h? xiǎnzǎi gèng hǎo kǎn.

Niánqīng rén dōu xǐhuan wánr.

While the idea of Being young is often niánqīng rén usually means people from

When she was young she was even more Beautiful than now.

All young people like to have fun.

zǒng: "always, invariaBly" Like other adverts such as zhēn, "really and hái, "still," zǒng is often followed By shi.

Nǐ zǒngshi wen wo wèntí. You always ask me questions.

’There are other words for "long" in other contexts. When referring to distance, use yuǎn: Lu hen yuǎn, "it’s a long way." For time, you will also need jiǔ: Tā zǒule duo jiǔ le?, "How long has it Been since he left?"

’’Remember that xiǎo is another word for "young": Tā hǐ wǒ xiǎo yísuì, "He’s a year younger than I." Wǒ xiǎode shihou usually means "When I was a child. When speaking to a child, you would say Nǐ hái xiǎo for "You’re still young.”

Zheizhong shiqmg zongshi rang This type of thing always makes one rén hen gāoxìng. very happy.

Zong bù, ’’always notis one way of saying ’’never”:

Tā zong bù xǐhuan biérén wen tā He never likes other people to ask jiālide shi. about his family.

Zong has another use, which is the one you see in exchange U: Instead of meaning literally ”on every occasion” or ”at all times,” zong is used to suggest that a certain state of affairs should be obviously true, regardless of other circumstances. Translations for this meaning depend upon the context; some are ’’after all, surely, always, in any case, when all is said and done, inevitably, eventually.” Other possible translations are suggested in

the following examples.

Xiāoháizi zong shi xiāohāizi, dale jiu hǎo le.

Nǐ bú jiè wo, wǒ zài zhèr kàn-kan zong kéyi ba?

Nǐ niàn shū shi hǎo shi, zong bù néng bù chī fan ba?

Nǐ shi Měiguo rén, nǐ zong bù néng bù zhīdào Eézhōu zài nǎr ba?!

Nǐ názǒu wǒde shū, zong děi wen wo yíxià!

Zong you yìtiān, tā huì huílaide.

Èrshige bū gou, nà nǐ shuō sān-shige zong gòu le ba?

A: Gōnggòng qìchē méiyou dào nèige dìfangde, women děi qí zìxíngchē qu.

B: Ou, qí chē duo lèi...

A: Zong bǐ zǒuzhe qù hǎoduō le.

Lai wǎn yidiǎnr zong bǐ bù lai hǎo.

Children will be children; after they grow up it will be better.

If you won’t lend it Cthis book] to me, at least I can read it here, can’t I?

It’s great that you’re studying, but after all, you can’t go without eating, can you?

You’re an American, you can’t very well not know where Texas is, can you?!

You really should ask before you take one of my books.

Someday he will surely come back.

If twenty isn’t enough, then thirty should surely be enough, wouldn’t you say?

There aren’t any buses that go there. We’ll have to go by bicycle.

Oh, but it’s so tiring to ride a bicycle.

Well, it’s much better than walking!

It’s better to come a little late than not to come at al 1.

A: Guānyu nǐ zhèige wentí, wo zhīdaode bù duo, dǎgǎi méiyou bǎnfǎ huídáhǎo.

B: Nǐ zǒng zhidaode "bǐ women duō, jiù qǐng ni jiǎngjiang ba!

I don’t know much about this question of yours. I probably can’t give you a good answer.

In any case, you know more than we do, so please try.

5. A: Shǔjiǎde shihou, nǐ xiǎng Where do you want to go dào nǎr qu wánrwanr? over summer vacation?

B: Wǒ xiǎng dǎo Yǎzhōu I’d like to go visit a few

jǐge guōjiā qu kǎnkan. countries in Asia.

Notes on No. 5

shǔjiǎ: "summer vacation" In China, summer vacation starts in August and ends in September for high schools; college ends in June and starts in late August.

Zhèige shǔjiǎ wǒ bǔ dǎo nǎr qù. This summer vacation I’m not going anywhere.

Yǎzhōu: "Asia" Yǎ comes from the transliterated word for Asia, Yǎxìyǎ. Zhōu means "continent." Many people say Yǎzhōu.

guōjiā: "country, nation, state," literally, "country-family." The bound word -guō is used only in certain phrases or compound words. Guōjiā is the word to use everywhere else. (Sometimes guō may be used alone, such as in reference to kingdoms or dukedoms of ancient China. But a modern nation is called guōjiā.)

6. A: Zěnme, nǐ xiǎng yānjiū Yǎzhōude wenhuǎ chuāntǒng?

B: Bù néng shuō yānjiū. Wo zhǐ shi xiǎng qù kǎnkan nǎlide shèhuì qíngkuǎng.

Notes on No. 6

Zěnme?: "oh?; what?; really?" tion.

Zěnme, nǐ yě dǎo zhèr lai le!

Zěnme? Tā bú shi Zhōngguo rén? Nǎ tāde Zhōngwén zěnme zenme hǎo ne?

A: Nǐ xiǎwu you shíjiān ma?

B: Zěnme? You shi ma?

Oh? Do you want to do research on Asia’s cultural tradition?

It can’t be called research. I just want to go have a look at the social situation there.

The intonation can change the implica-

Well, you’ve come here too!

What? He’s not Chinese? Then how is his Chinese so good?

Do you have any time this afternoon?

Why? Is something happening?

wénhuà: "culture, civilization" Also "education, cultural background" as in meiyou wénhuàderén, "an uncultured person" or an "uneducated person."

shèhuì: "society; social" Xīn shèhuì and jiù shèhuì are jargon for the new and old societies (after and before the socialist transformation). "in society" is more often zai shèhuìshang, less frequently zài shèhuìli.

Xiānggǎngde shèhuì wèntí zhēn Hong Kong sure has a lot of social duō. problems, (e.g., drugs, killings)

7. A: Lao Wang, wǒ jīntiān gǎnjué hen bu shūfu.

B: Kuài zuòxia, wǒ qù gěi ni dào bēi chá lai.

Notes on No. 7

ganjué: "to feel; feeling" In are other examples:

Nǐ gǎnjué zǒnmeyàng?

Nǐ jīntiān gǎnjué hǎo yidiǎnr le ma?

Wǒ gǎnjué tā jīntiān you diǎnr bu gāoxìng.

Suīrán wǒ bù fā shāo le, kǒshi zǒng gǎnjué hen lèi.

Here is an example of gǎnjué used as

Lǎo Wang, I feel awful today.

Sit down and I’ll go get you a cup of tea.

Zhèi shi wǒde gǎnjué, nǐde kànfa zenmeyàng?

7a, gǎnjué is used as a verb. Here

How do you feel?

Do you feel better today?

I get the feeling he’s a little unhappy (OR bothered) today.

Although I don’t have a fever any more, I feel very tired all the time.

a noun:

That’s my feeling, what is your opinion?

zuòxia: "to sit down" Also zuòxialai.

Qǐng zuòxia(lai) tan.

Have a seat and let’s talk about it.

dào...lai: Dào is "to pour"; dàolai is "to pour and bring here," You have seen lai used as a directional ending before, as in nǎxialai, "bring down and here," or pǎolāi "run here." There are two things to notice about the meaning of lai as a directional ending: 1) Lai can be used after verbs which tell of movement from one place to another, like pǎo, "to run" or nǎ, "to carry"; OR after verbs which describe an action without movement from one place to another, such as dào, "to pour." 2) The thing lai refers to, which is what ends up "here," may be the subject OR the object of the sentence. For example, in Tā pǎolai le, "He ran here," it is the subject tā who performs the action of running and comes here. In Tā xiělai yìfēng xìn le, "He has written a letter which has come here," it is the object xìn which is

•written and comes here. In Yīfu dōu yǐjīng xǐlai le, "All the clothes have already "been washed and brought here," it is the topic yīfu which were washed and brought here.

You will often split lai from the verb by inserting an object like yìbēi chá, as in sentence 7B. In fact, in sentence 7B, dào and lai must be split up; lai may not precede the object. The rules allowing lai to precede the object are complex, and here we will just give some examples of usage.

Nǐ nǎr jièlai zhème yíliàng pò Where did you borrow such a beat-up

chē?.*

old car from?

Wǒ zuì xǐhuan nǐ cóng Shanghai mǎilaide nèijiàn máoyī.

I like the sweater you bought in Shanghai best.

Wǒ yídìng gěi ni zhǎolai nèiběn shū OR Wo yídìng gěi ni zhāo nèiběn shū lai.

I’ll be sure to find that book for you.

Nǐ shénme shíhou you shíjiān, da ge diànhuà lai, women yìqǐ qù kàn diànyǐng.

When you get the time, give me a call, and we’ll go see a movie together. (Lai must follow the object.)

Bié^wàngle míngtiān yě bā nǐde nūpéngyou dàilai.

Don’t forget to bring your girlfriend tomorrow too.

8. A: Nǐ qùde nèige dìfang,

zhèngzhi, jīngji fāngmiànde qíngxing zěnmeyàng?

What was the political and economic situation like where you went?

B: Jǐjù huà shuǒbuqīngchu,

you shíjiān wo zài gēn ni mànmānr shuō ba.

I can’t explain it clearly in just a few sentences; when I have time I’ll tell you all about it.

Notes on No. 8

fāngmiàn: "aspect; area; respect; side" This noun is used without a counter. It is a useful, sometimes overused word. You won’t have any trouble understanding how fāngmiàn is used, but there will be sentences where you wouldn’t have thought to use it. When translating, it is sometimes better just to leave fāngmiàn out of the English than to strain to use the word "aspect," "side," etc.

Fāngmiàn has two main uses:

(1) "aspect, respect, area, field"

Zhèige wèntí you liǎngfāngmiàn. There are two aspects to this

question.

Women zài zhèifāngmiàn zuòde hái bū gèu.

We haven’t done enough in this area.

Yīngguó zài jīngjixué fāngmiànde yánjiǔ zuòde bù shǎo.

Wǒ méi shide shihou xǐhuan kankan wénxué fāngmiànde shū.

A lot of research in the area of economics has been done in England

When I don’t have anything to do I like to read books on the subject of literature.

A: Wǒ kànle nǐ xiede yǐhòu juéde you yìfāngmiàn kéyi xiede gèng hǎo.

B: Nǎifāngmiàn ne?

(2) "party, side," referring to

Niǔyuē fāngmian dàgài bú huì you shénme wentí , kěshi women yīnggāi he Beijing fāngmian xiān shāngliang yixia zài shuǒ.

Guānyu zhèige wèntí, liǎng fāngmiànde kànfǎ you diǎn bù tong.

After reading what you wrote, I feel there’s one respect in which you can make it better.

What respect?

a group of people

New York won’t have any problem with this, but we should check with Beijing before going ahead, (meaning groups of people, e.g., offices of a company.)

The two sides have somewhat different views on this question.

qíngxing: In most cases interchangeable with qíngkuàng. In present-day Beijing speech, at least among the younger generation, qíngkuàng is the more common of these two words.

shuōbuqingchu: "can’t say/explain clearly" Shuōqingchu is a compound verb of result. Here are other examples:

Wo shuobuqingchu wèishenme tā shěngqì.

Bù shuōqīngchule bù xíng.

Tā shuōqīngchule tāde mùdi.

Nǐ néng bu néng shuōqingchu "niánqīng" he "xiǎo" de bù tong?

I can’t really explain why he got angry.

It won’t do not to explain it clearly.

He explained his goal clearly.

Can you explain clearly the differences .between niānqing and xiǎo?

mànmānr: Also mànmàn. Many adjectival verbs can be doubled to make an adverb, which is used between the subject and the verb. In Beijing speech, when you double certain adjectival verbs of one-syllable, the second one becomes first tone (no matter what its original tone) and -r is added. These adverbs can take the adverbial ending -de. Other examples are kuàikuāir(de), "quickly," and hǎohāorde, "well, properly."

Mànmàn(de) or mànmānr(de) has these meanings:

(1) "slowly" Don’t forget, however, that "slowly" can sometimes be translated by màn alone.

Tā manmānrde zou hui jia qu le. He slowly walked, home.

BUT Zǒu man yidiānr. I

Man diǎnr zǒu. ( Walk more slowly.

(2) "gradually, bit by bit, by and by"

Nǐ gang lai, duì zhèrde qíngkuàng You just arrived and are unfamiliar bù shúxī, mànmānr. nǐ jiu zhīdao with the situation here, but you’ll le. come to know it by and by.

Manmānrde, tā jiu dong le. Gradually he began to understand.

(3) Sentences which instruct someone to mànmānr do this or that

can often be translated as take your

Mànmānr zou, zānmen láidejí.

Bù jí, mànmānr chī, wǒ děng nǐ.

(U) With verbs meaning "to tell" more of the meaning "in all details."

Nǐ zuòxia, wǒ mànmānr gēn ni jiǎng.

Wǒ hai xiāng gēn ni duō tantan zhèijiàn shi.

Hǎode, yīhòu women mànmàn tan.

time..., or "don’t rush."

Let’s take our time walking. We’ll make it.

There’s no hurry, so take your time eating. I’ll wait for you.

someone about something, mànmānr has

Sit down and I’ll give you the whole story.

I’d like to talk some more with you about this.

Okay, later we can talk all about it.

9. A: Yánjiū Zhōngguo xiànzàide wèntí yídìng děi dǒngde Zhōngguo lìshǐ.

B: Nǐ shuōde zhèiyidiān hěn yàojǐn, wǒ kāolu kāolù.

To study the problems of China now, you have to understand Chinese history.

This point of yours is very important; I’ll think it over.

Notes on No. 9

dǒngde: "to understand" Narrower in use than dǒng. You dǒngde the meaning of a word, the implications or significance of an event, or the way to do something; but not a foreign language (that you dǒng), nor what the teacher just said (that you tǐngdǒng le), nor someone else’s feelings (that you liāojiě, which will be presented in the Traveling in China module).

You have seen the component -de in the verbs rènde and j ide. It is only used in a handful of verbs, sometimes acting like a resultative ending. For example, you can say rènbude, "can’t recognize," and jìbude, "can’t remember," but you may not use dǒngde in the potential form; for "can’t understand," you just say bù dǒngde.

-dian: ’’point" (For the second one ’ s heart. ’’)

b, hái you yìdiǎn.

Zhèi shi rang rén xīnli zuì bù shūfude yìdiǎn.

Nèi yidiǎn women ’yǐjīng tánguo le.

Wǒ juéde tā shuōde měiyidiǎn dōu duì.

example, you need to know xīnli, "in

Oh, there’s one more point Cthat should he made!.

This is the most upsetting point.

We’ve been over that point already

I think that every point of his was right.

kǎolù: "to consider, to think over; consideration"

Zhèi yidiǎn women yīnggāi kǎolū.

Wo děi hǎohāor kǎolù zhèige wèntí.

Zhèi fāngmiǎnde qíngkuàng nǐ kǎolùle ma?

We should consider this point.

I have to think this matter over carefully.

Have you taken this aspect of the matter into consideration?

10. A: Nǐ zài Zhongguo zhù liǎng-niàn, yídìng huì xuéhǎo Zhōngwénde.

B: Shi a, yìfàngmiàn kéyi xuéhǎo Zhōngwén, yìfàngmiàn yě kéyi duō zhīdao yidiǎnr Zhōngguode shìqing.

Notes on No. 10

huì: "might, be likely to, will" how to, can." Here you see huì used i

If you live in China for two years you’re sure to learn Chinese very well.

Yes, on the one hand I can learn Chinese well, and on the other hand I can find out more things about China.

You already know huì meaning "to know a new way, to express likelihood. As

you can see from these three English translations, huì ranges in meaning from possible to probable to definite. The context may be sufficient to indicate which, but often the degree of probability is not important to the message, and there might be no single "correct" English translation. Various adverbs can be added before huì to clarify the degree of certainty, for example, yídìng, "definitely," dàgài, "probably," yěxǔ, "perhaps," etc.

Here are some examples of how huì can be used to indicate likelihood:

huì

Yǐjīng shíèrdiàn ban le, zhè shíhou shéi huì lai ne?

Yídìng yào wǒ qù, tā cài huì qù.

It’s half past twelve. Who would come at this hour?

I’ll have to go or else he won’t go.

Cai yàoshi fàngde tài duo le, háohǐng huì pǒ.

Nǐde chènshān zāngle t>ú yàojǐn, wǒ huì gěi nǐ xǐ.

If you put too much food in, the pancake will break.

It doesn’t matter that your shirt got dirty. I’ll wash it for you.

Bú da huì ha?

Dàgài hú huì shi tā.

Yàoshi zài Taiwan mǎi jiù hú huì zhème guì le.

Nǐ hú huì zhǎohudào ha?

Nǐ hú yào jí le, wǒ hú huì chū shi de.

huì...ma?

Nǐ kàn jīntiān wǎnshang huì liāngkuai yidiàn ma?

Tā huì qù ma? Tā huì qù.

huì hu huì

Míngtiān tā huì hu huì lai?

Women xiede neifēng xìn, dào xiànzài tāmen hāi méiyou shōudào, women huì hu hui xiǒcuǒle dìzhǐ?

Wǒ hǎ men kāi le, zhèiyang nǐ huì hu hui juéde tài lěng?

Nǐ kàn jīntiān huì hu hui xià yú?

That’s not very likely.

It’s prohahly not him.

If you "buy it in Taiwan, it won’t he so expensive.

You won’t he unahle to find it, will you?

Don’t get anxious, I won’t have an accident.

Do you think it might he cooler tonight ?

Will he go? He’ll go.

Will he come tomorrow?

They still haven’t gotten the letter we wrote. Could we have written the address wrong?

I opened the door. Will you feel too cold like this?

Does it look to you as if it might rain today?

nǐ huì zǒucuǒde: So far you have seen -de used as a marker of possession or of modification, and in the shi... de construction. Here it is used in an entirely new way: at the end of a sentence, -de can mean ’’that’s the way the situation is.” Generally speaking, this -de is used in emphatic assertions or denials, especially those expressing prohahility, necessity, desire, etc.

Usage note: Unless the sentence contains shi or is understood to have an omitted shi, the majority of native Běijīng speakers seem to feel that this -de is nānfāng huà, southern Chinese (e.g., Nānjīng), or a carry-over into Standard Chinese from southern dialects. Because of these regional connotations you needn’t try to use it a lot; it will he enough for you to understand this -de; in fact, you will see that in most of the following examples, the -de is completely unnecessary.

(1) Sentences with shi in the sense of ”it is that..., it is a case of..." This shi may often he omitted.

Wǒ shi bú qùde.

Zhèige, nǐ shi zhīdaode.

Nèige rén (shi) you wèntíde.

I’m not going. (More literally, "As for me, it is that I’m not going.")

This you know.

There’s something wrong with that guy

A: Nǐ zěnme lai le?

B: (Shi) Lǐ Xiānsheng jiao wo laide.

Cóngqián wǒ cóng Xianggang mǎi shūde shihou, měicì dōu (shi) jì zhīpiàode.

Why are you here?

Mr. Lī told me to come.

In the past whenever I have bought (mail-order) books from Hong Kong, I have always paid by check (lit. , "sent a check").

(2) Sentences with an auxiliary verb (huì, néng, yào, yǐnggāi, etc.)

Nǐ gàosu ta, tā huì shēngqìde. If you tell him he’ll get angry.

Zài xiě yìliǎngge zhōngtóu, wǒ xiǎng néng xiěwánde.

Nǐ zěnme méi mǎi a, yìdiǎn dōu bú guì, nǐ yǐnggāi mǎide.

Nǐ zhème bù shūfu, jīntiānde huì nǐ bù yǐnggāi qùde.

Women zǒng you yìtiān yào hui dàlùde.

If I write for another hour or two, I think I can finish writing it.

How come you didn’t buy it? It’s no' at all expensive. You should have bought it.

Since you’re feeling so ill, you shouldn’t go to today’s meeting.

There will come a day when we will go back to the mainland.

(3) Others: sentences with certain adverbs like yídìng, with potential resultative verbs, with the aspect marker -guo, etc.

Zhèixiē shū yídìng xūyàode.

Wǒ hē kāfēi cónglái bù fang tāngde.

Mápó Doùfu píngcháng dōu you ròude.

Wǒmende gōngzuò zhēnshi tài duō le, zuòbuwánde!

Zhèige diànyǐng wǒ cóngqián kànguode.

These books are definitely needed I never take sugar in my coffee.

Mápó Beancurd usually has meat in

We really have an awful lot of wo: We’ll never be through with it.

I’ve seen this movie before.

Bu yàojǐnde.

Hǎode, hǎode.

yìfàngmiàn...yìfàngmiàn...: This hand..., on the other hand...” or ’’for and (2) ’’doing—while doing..."

Zài Xianggang yìfàngmiàn nǐ you jīhui he Zhongguo rén tan huà, yìfāngmiān kéyi zhīdao dàlùde qíngkuàng.

Tā yìfàngmiàn kàn diànshì, yì-fāngmiàn chī dōngxi.

11. yìbiān(r)...yìbiān(r)...

12. yímiàn(r)...yímiàn(r)...

It doesn’t matter.

All right, all right.

has two meanings: (1) "on the one

one thing...» for another thing..."

In Hong Kong, on the one hand you’ll have a chance to talk with Chinese and on the other hand you can learn about the situation on the mainland

He watches television while eating.

doing...while doing ...

doing...while doing ...

Notes on Nos. 11 and 12

yìbiān(r)...yìbiān(r)... and yímiàn(r)—yímiàn(r)...: "doing...while doing..." Both of these patterns are similar to the second meaning of yìfāngmiàn. ..yìfàngmiàn....

Yìbiān zuò yìbiān xué ba.’

Wǒ yìbiānr ting yìbiānr xie.

Women yìbiān zǒu yìbiān tan, hāo bu hǎo?

Learn by doing (learn as you do it)!

I write as I listen.

Let’s talk as we walk, okay?

Unit 1, Tape 1, Review Dialogue

As Tom (A) (Tāngmú), a graduate student in Chinese Area Studies at Georgetown University, is studying in his apartment, a knock comes at the door It is his classmate Lǐ Ping (B), an exchange student from Hong Kong.

A: A! Shi ni ya! Hao jiu hu jian!

Jīntiān zěnme you shíjiān chūlai zǒuzou?

B: Yíge zhōngtóu yǐqián, wǒ cóng

xuéxiào gěi ni dǎ diànhuà, nǐ hu zài jiā, gāngcái wǒ dào zhèli fǔjìn mǎi dōngxi, jiu lai kàn-kan. Zhēn hu cuò, nǐ yǐjīng huilai le.

A: Duìhuqǐ, wǒ gāngcái dào

péngyou jiā jiè shū qu le.

B: Shénme shū? You shi guānyú

Zhōngguóde ha?

A: Duì le, you Xiānggǎngde,

dàlùde, yě you Taiwānde, dōu shi xiǎoshuōr. Nǐ zuòxia kàn, wǒ qù gěi ni dào hēi chá lai.

B: Bu yào máfan, shénme hēde dōu

xíng.

A: Kěkǒukělě, júzi shuǐr°, háishi

píjiǔ?

B: M, júzi shuǐ ha!

A: Hǎo, wǒ mǎshàng jiù lai, yào

hīngkuàir ma?

B: Bú yào, xièxie.

(Lǐ Ping sits down and leafs th: two glasses of orange juice.)

Well, it’s you! I haven’t seen you in a long time! How is it you’ve got time to come out for a walk today?

I called you an hour ago from school, hut you weren’t home. I just came over to this neighborhood to do some shopping, so I stopped hy to visit. It’s great that you’re hack already.

Sorry. I just went over to a friend’s house to borrow a book.

What book? More about China, I het.

Yes, there are ones from Hong Kong, the mainland and Taiwan, all fiction. Sit down and have a look. I’ll go get you a cup of tea.

Don’t go to any trouble. Anything to drink is fine.

Coke, orange juice or beer?

Um, orange juice.

Okay, I’ll get it right now. Do you want ice cubes?

No, thanks.

igh the books, and Tom returns with

B: Tāngmǔ?!

A: Ng?

B: Zhè sānge dìfangde shū, nǐ dōu

kàn, nǐ juéde zěnmeyàng?

A: Wǒde gǎnjué bú shi yíjù huà

Tom?

Yeah?

Reading books from all three of these places, what do you think?

I can’t explain my feelings in

°Kěkǒukělè, ’’Coca-Cola”; júzi shuǐ(r), "orange juice” (Běijīng usage)

kéyi shuōqīngchude. Eng... zhème shuō ba, wo zǒng juéde dàlù rén, Xianggang rén, hé Taiwan rén dōu shi Zhōngguo rén, tāmen you yíyàngde wénhuà chuán-tǒng, kěshi yīnwei zhèngzhide qíngkuang bù tong, shèhuìde qíngkuang yě jiu bù yíyàng le.

B: Nǐ shuōde duì, dànshi nǐ yào

dongde Zhōngguo shèhuì, zhǐ kàn shū shi bū gòude.

A: Ei, ni zhidao ma, xianzai xue

Zhōngwénde xuéshēng you hěn duō jīhui dào Zhōngguo qu. Suǒyǐ wǒ jìhuà zài zhèige xuéqǐ wánle de shihou, qù Zhōngguo kànkan. Erqiě, wǒ hái xiǎng zhǎo ge hǎo péngyou yìqǐ qù.

B: Zuótiān wǒ jiēdao wǒ mǔqinde

xìn, tā xīwàng wǒ hui Xiānggǎng guò shǔjià; zěnmeyàng, nǐ hé wo yìqǐ huíqu ba. Nǐ kéyi zhù zai women Jiāli, érqiě, zài Xiānggǎng yìfāngmiàn nǐ you jǐhui hé Zhōngguo rén tan huà, yì fāngmiàn kéyi zhīdao dàlù, Xiānggǎng hé Tai-wǎnde qíngkuàng, nǐ kàn hǎo bu hǎo?

just a few words. Hmm...let’s say that I’ve always felt that people on the mainland, in Hong Kong and Taiwan are all Chinese, all have the same cultural tradition, but because the political situations are different , the social situations are also different.

You’re right. But if you want to understand Chinese society, it’s not enough just to read books.

Say, you know, students of Chinese have a lot of opportunities to go to China now. So I’m planning to go to China for a visit when this semester is over. And what’s more, I’d like to find a good friend to go with.

Yesterday I got a letter from my mother, and she’d like me to come back to Hong Kong for summer vacation. How about going back with me? You can stay at our house; what’s more, in Hong Kong, on the one hand you’ll have a chance to talk with Chinese and on the other hand you can learn about the situation on the mainland, in Hong Kong and in Taiwan. What do you think?

A: Fēichāng hǎo!

B: Name, nǐ hái yào hé nǐ jiāli

rén shāngliang yixiar ba?

A: Bu bì, gěi fùmǔ dǎ diànhuàde

shihou, gàosu tamen wǒde jìhua jiu xíng le. Wǒ yào yánjiū Zhōngguo shèhuì, fùmǔ yídìng huì gāoxìngde.

B: Měiguo niánqīng rén dōu you

zìjǐde xiǎngfǎ, zhèi yidiǎnr, wǒ fēicháng xǐhuan.

A: Niánqīng rén you zìjǐde xiǎngfǎ

shi duìde, kěshi fùmǔde huà yě yīnggāi kǎolù.

Great!

Well then, you’ll still want to discuss this a bit with your parents, I suppose?

That’s not necessary. When I call them, I’ll tell them my plan, and then everything should be all right. I’m sure they’ll be happy that I want to study Chinese society.

Young people in America really think for themselves (have their own ideas). I really like that.

It’s good that young people think for themselves, but you still ought to consider what your parents say.

% v w — w

B: M. Na women shuohao le, jin-

nián shǔjià qù Xianggang, xiàn-zài hái you wǔge yuède shíjiān kéyi zhǔnbèi.

A: Duì, jiù zhème ban! Jīnnián

xiàtiān wǒ jiù yào dào zhèige dìfang dà, rénkǒu duo, lìshǐ you chángde guǒjiā qu le. Hai! Zhèige jìhua zhēn rang wo gāoxìng!

B: Hǎo, jiù zhèiyang. Wǒ yīnggāi

zǒu le!

A: Nǐ máng shenme! Hái zǎo ne!

B: Bù. zǎo le, huíqu hái dei niàn

shū ne!

A: Nà, you shíjiān nǐ zài lái

wánr!

B: Hǎo, míngtiān jiàn.

A: Míngtiān jiàn!

Mm. Well then we have decided.

This summer vacation we’ll go to Hong Kong. We still have five months to prepare.

Right, that’s what we’ll do. This summer we will go to that country with a large area, a great population, and a long history. Boy, this plan really makes me happy.

Good, it’s settled. I have to go.

What’s the hurry? It’s still early!

No it isn’t. I still have to study when I get back.

Well then, come again when you have time!

Okay, see you tomorrow.

See you tomorrow.

Exercise 1

This exercise is a review of the Reference List sentences in this unit. The speaker will say a sentence in English, followed by a pause for you to translate it into Chinese. Then a second speaker will confirm your answer.

All sentences from the Reference List will occur only once. You may want to rewind the tape and practice this exercise several times.

Exercise 2

This exercise contains a conversation in which a Chinese mother and son, who have lived in the United States for five years, discuss the possibility of his taking a summer trip to China.

The conversation occurs only once. you’ll probably want to rewind the tape listen a second time.

Here are the new words and phrases conversation:

xīnshì

zhangdà

dàxuéshēng

gèguó

gaozhōng

hǎohāor

jìzhu

After listening to it completely, and answer the questions below as you

you will need to understand this

something weighing on one’s mind, worry

to grow up

college student

various countries

senior high school

properly, carefully, thoroughly

to remember

Questions for Exercise 2

Prepare your answers to these questions in Chinese so that you will be able to give them orally in class.

1. How does Xiǎo Ming’s mother know that something is on his mind? How does she bring up the subject?

2. What are his classmates doing over the summer?

3. Why does he think Asian culture is interesting?

How does Xiǎo Ming’s mother react to his idea?

5. What advice does she give?

After you have answered these questions yourself, you may want to take a look at the translation for this conversation. You may also want to listen to the dialogue again to help you practice saying your answers.

Note: The translations used in these dialogues are meant to indicate the English functional equivalents for the Chinese sentences rather than the literal meaning of the Chinese.

Exercise 3

In this conversation a Chinese student studying at a university in the U.S. comes home on a Friday night and finds his American roommate engrossed in his studies.

Listen to the conversation once straight through. Then, on the second time through, look below and answer the questions.

Here are the new words and phrases you will need to understand this conversation:

|

Wǒde tian na! |

My God.’ |

|

xuéshēnghuì |

student association |

|

guānxīn |

to be concerned about |

|

jìndǎishǐ |

modern history |

|

xiàndài |

modern |

|

pǐchá bǐng |

pizza |

|

gǔshū |

ancient books |

Questions for Exercise 3

Prepare your answers to these questions in Chinese so that you will be able to give them orally in class.

1. Why does the Chinese student object to his roommate studying the classics?

2. Why doesn’t the American student like to talk about politics?

3. What other subjects does the Chinese student feel his roommate should become familiar with for a well-rounded education?

U. Does the American student agree? Why or why not?

5. What will the roommates do after the American student finishes his homework?

After you have answered these questions yourself, you may want to take a look at the translation for this conversation. You may also want to listen to the conversation to help you practice saying the answers which you have prepared.

Exercise H

In this exercise, an American university student visits her Chinese literature professor after class in his office.

Listen to the conversation straight through once. Then rewind the tape and listen again. On the second time through, answer the questions.

You will need the following new words and phrases:

jīdòng

liùshi niándài

yǐ

gǎibiàn

liúxia

to get worked up, to be agitated

the decade of the sixties

as soon as

change(s)

to leave

Questions for Exercise U

1. Why was Professor Tang so upset in class?

2. Why did the student visit her professor?

3. What things does she bring him? Why?

U. What recent changes have there been in the state of Chinese literature?

5. What is Professor Tang’s attitude about the future?

After you have answered these questions yourself, you may want to take a look at the translation for this conversation. You may also want to listen to the conversation again to help you pronounce your answers correctly.

Dialogue and Translation for Exercise 2

A mother and her son who immigrated to America from China five years ago are talking after dinner:

A: Xiao Ming, nǐ zài chǐ yidiǎnr Xiao Ming, have some more to eat.

a.

B: Mǎ, wǒ chībǎo le, bù xiang chǐ

le.

A: Měitiǎn niàn shū niànde zhème

wan, zài bu duō chǐ yidiǎnr, zěnme xíng na?

B: Wǒ zhēnde chǐbǎo le, yidiǎnr

dōu bù xiǎng chǐ le.

A: Hǎizi, nǐ you shénme xǐnshì

Kě bu kéyi hé wo tantan?

B: Mǎ, nǐ zuòxia. Zǎnmen lai

Měiguo sìwǔnián le, laide shihou wǒ hai shi ge haizi, xiànzài yǐjīng shi dàren le. Wo suīrán zhǎngdà le, keshi zuo shénme shir, hǎishi xiǎng xiǎn hé nín tantan.

A: Hǎode, you shénme shir, nǐ

jiù shuō ba!

B: Mǎ, wǒ you Jīge Meiguo tong-

xué, dōu shi xué Zhōngwénde, jīnniǎn shǔjià, tǎmen xiǎng dào Yàzhōu qù kànkan, wǒ yě xiǎng hé tǎmen yìqǐ qù.

A: Dōu shi nianqīng rén ma?

B: Shi a, dōu shi dàxuéshēng.

A: Tǎmen qù Yǎzhōu, shi qù wanr

haishi qù yǎnjiù Yǎzhōude zhèngzhi, wénhuà qíngxing?

B: Wǒ xiǎng, tǎmen juéde Yàzhōu

wénhuà hěn you yìsi, Yàzhōu gèguo shèhuìde qíngkuàng ye hěn you yìsi.

I’m full, Mom. I don’t want any more.

You study so late every day, if you keep eating so little, how will that do?

I’ve really had enough. I just don’t want any more.

Son, what do you have on your mind? Can you talk about it with me?

Mom, sit down. We’ve been in America for four or five years now. When we came I was still a child, but now I’m an adult. But even though I’ve grown up, whenever I do something I still like to discuss it with you first.

Okay, if you have something you’d like to talk about, go ahead.

Mom, I have a few American classmates who study Chinese. This summer vacation, they want to go to Asia, and I’d like to go with them.

Are they all young people?

Yes, they’re all college students.

Are they going to Asia for fun or to study the political and cultural situation in Asia?

I think they find Asian culture and the social situation in the Asian countries very interesting.

A: Tāmen juéde zuì you yìside

dìfang shi nǎr a?

B: Dǎngrǎn shi Zhōngguo!

A: Nǐ líkāi Zhōngguo zhǐ you

sìwǔniǎn, jiù xiǎng huíqu le?

B: Wō láide shihou cǎi shàng

gǎozhōng, duì Zhōngguo wénhuà dōngdéde tài shǎo. Wō xiǎng wō yīnggǎi huíqu kankan.

A: Zhōngguode wénhuà yǐjīng you

sìqiānniánde lìshǐ, yōu yìside dōngxi hen duō. Nǐ yào yǎnjiǔ Zhōngguo wénhuà, wō hu fǎnduì. Būguò, zōu yǐqiǎn, nǐ yídìng yào he Yéye hǎohǎor tan yícì. Tā jǐshíniǎn méiyou huíqu le, yídìng yōu hěn duō huà yào he ni shuō.

B: Wō Jìzhu le, yídìng he Yéye

hǎohǎor tanyitan.

Which place do they think is the most interesting?

China, of course!

You left China only four or five years ago, and already you want to go hack again?

When I came I was only in senior high, and I understood too little about Chinese culture. I think I ought to go hack to visit.

Chinese culture already has four thousand years of history, and there are many interesting things. I’m not against your wanting to study Chinese culture. But before you go you have to talk it over thoroughly with Grandpa. He hasn’t been back in several decades and I’m sure he’ll have a lot to say to you.

I’11 remember. I’ll make sure I talk it over thoroughly with Grandpa.

Dialogue and Translation for Exercise 3

Two classmates, an American (B) and a Chinese (A), share an apartment somewhere in America. The American is at home studying Shǐ Jì, Records of the Historian, a classical history. His Chinese classmate comes in the door.

A: Wōde tiān na! Nǐ hai zài niàn My God! Are you still studying?

shū? Ài, he běi píjiǔ xiūxi Hey, how about taking a break for xiuxi hǎo bu hǎo? a beer?

B: Hǎo hǎo hǎo, ràng wo bǎ

zhèiyidiǎnr kànwǎn xíng bu xíng?

A: Hài, nǐ zōngshi kàn gūshū!