CM 0180 S

A MODULAR APPROACH

STUDENT TEXT

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION

MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

SPONSORED BY AGENCIES OF THE

UNITED STATES AND CANADIAN GOVERNMENTS

This publication is to be used primarily in support of instructing military personnel as part of the Defense Language Program (resident and nonresident). Inquiries concerning the use of materials, including requests for copies, should be addressed to:

Defense Language Institute

Foreign Language Center

NonresidentTraining Division

Presidio of Monterey, CA 93944-5006

Topics in the areas of politics, international relations, mores, etc., which may be considered as controversial from some points of view, are sometimes included in the language instruction for DLIFLC students since military personnel may find themselves in positions where a clear understanding of conversations or written materials of this nature will be essential to their mission. The presence of controversial statements-whether real ōr apparent-in DLIFLC materials should not be construed as representing the opinions of the writers, the DLIFLC, or the Department of Defense.

Actual brand names and businesses are sometimes cited in DLIFLC instructional materials to provide instruction in pronunciations and meanings. The selection of such proprietary terms and names is based solely on their value for instruction in the language. It does not constitute endorsement of any product or commercial enterprise, nor is it intended to invite a comparison with other brand names and businesses not mentioned.

In DLIFLC publications, the words he, him, and/or his denote both masculine and feminine genders. This statement does not apply to translations of foreign language texts.

The DLIFLC may not have full rights to the materials it produces. Purchase by the customer does net constitute authorization for reproduction, resale, or showing for profit. Generally, products distributed by the DLIFLC may be used in any not-for-profit setting without prior approval from the DLIFLC.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach originated in an interagency conference held at the Foreign Service Institute in August 1973 to address the need generally felt in the U.S. Government language training community for improving and updating Chinese materials, to reflect current usage in Beijing and Taipei.

The conference resolved to develop materials which were flexible enough in form and content to meet the requirements of a wide range of government agencies and academic institutions.

A Project Board was established consisting of representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency Language Learning Center, the Defense Language Institute, the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute, the Cryptologic School of the National Security Agency, and the U.S. Office of Education, later Joined by the Canadian Forces Foreign Language School. The representatives have included Arthur T. McNeill, John Hopkins, and John Boag (CIA); Colonel John F. Elder III, Joseph C. Hutchinson, Ivy Gibian, and Major Bernard Muller-Thym (DLI); James R. Frith and John B. Ratliff III (FSI); Kazuo Shitama (NSA); Richard T. Thompson and Julia Petrov (OE); and Lieutenant Colonel George Kozoriz (CFFLS).

The Project Board set up the Chinese Core Curriculum Project in 1971* in space provided at the Foreign Service Institute. Each of the six U.S. and Canadian government agencies provided funds and other assistance.

Gerard P. Kok was appointed project coordinator, and a planning council was formed consisting of Mr. Kok, Frances Li of the Defense Language Institute, Patricia O'Connor of the University of Texas, Earl M. Rickerson of the Language Learning Center, and James Wrenn of Brown University. In the fall of 1977* Lucille A. Barale was appointed deputy project coordinator. David W. Dellinger of the Language Learning Center and Charles R. Sheehan of the Foreign Service Institute also served on the planning council and contributed material to the project. The planning council drew up the original overall design for the materials and met regularly to review their development.

Writers for the first half of the materials were John H. T. Harvey, Lucille A. Barale, and Roberta S. Barry, who worked in close cooperation with the planning council and with the Chinese staff of the Foreign Service Institute. Mr. Harvey developed the instructional formats of the comprehension and production self-study materials, and also designed the communication-based classroom activities and wrote the teacher’s guides. Lucille A. Barale and Roberta S. Barry wrote the tape scripts and the student text. By 1978 Thomas E. Madden and Susan C. Pola had Joined the staff. Led by Ms. Barale, they have worked as a team to produce the materials subsequent to Module 6.

All Chinese language material was prepared or selected by Chuan 0. Chao, Ying-chi Chen, Hsiao-Jung Chi, Eva Diao, Jan Hu, Tsung-mi Li, and Yunhui C. Yang, assisted for part of the time by Chieh-fang Ou Lee, Ying-ming Chen, and Joseph Yu Hsu Wang. Anna Affholder, Mei-li Chen, and Henry Khuo helped in the preparation of a preliminary corpus of dialogues.

Administrative assistance was provided at various times by Vincent Basciano, Lisa A. Bowden, Jill W. Ellis, Donna Fong, Renee T. C. Liang, Thomas E. Madden, Susan C. Pola, and Kathleen Strype.

The production of tape recordings was directed by Jose M. Ramirez of the Foreign Service Institute Recording Studio. The Chinese script was voiced by Ms. Chao, Ms. Chen, Mr. Chen, Ms. Diao, Ms. Hu, Mr. Khuo, Mr. Li, and Ms. Yang. The English script was read by Ms. Barale, Ms. Barry, Mr. Basciano, Ms. Ellis, Ms. Pola, and Ms. Strype.

The graphics were produced by John McClelland of the Foreign Service Institute Audio-Visual staff, under the general supervision of Joseph A. Sadote, Chief of Audio-Visual.

Standard Chinese: A Modular Approach was field-tested with the cooperation of Brown University; the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center; the Foreign Service Institute; the Language Learning Center; the United States Air Force Academy; the University of Illinois; and the University of Virginia.

Colonel Samuel L. Stapleton and Colonel Thomas G. Foster, Commandants of the Defense Language Institute, Foreign Language Center, authorized the DLIFLC support necessary for preparation of this edition of the course materials. This support included coordination, graphic arts, editing, typing, proofreading, printing, and materials necessary to carry out these tasks.

James R. Frith, Chairman

Chinese Core Curriculum Project Board

Introduction Section I: About the Course

MODULE 1: ORIENTATION Objectives ....................... .....

Reference Notes ......... . ......... ..... 28

Full names and surnames Titles and terms of address Drills

Given names

Yes/no questions

Negative statements

Nationality

Home state, province, and city Drills

Location of people and places Where people’s families are from

Appendices

MODULE 2: BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION Objectives

Where people are staying (hotels) Short answers The question word něige "which?" Drills............... 105

Where people are staying (houses) Where people are working Addresses The marker de The marker ba The prepositional verb zài Drills..........................120

Members of a family The plural ending -men The question word jl- "how many"

The adverb dōu ’’all"

Several ways to express "and" Drills . . .

Arrival and departure times

The marker le

The shi... de construction Drills

Date and place of birth

Days of the week

Ages

The marker le for new situations Drills

Reference List .... .......... ..........

Reference Notes ................ .......

Duration phrases

The marker le for completion

The "double le" construction

The marker guo

Action verbs

Where someone works

Where and what someone has studied What languages someone can speak Auxiliary verbs General objects

More on duration phrases The marker le for new situations in negative sentences Military titles and branches of service The marker ne Process verbs Drills............................223

This course is designed to give you a practical command of spoken Standard Chinese. You will learn both to understand and to speak it. Although Standard Chinese is one language, there are differences between the particular form it takes in Beijing and the form it takes in the rest of the country. There are also, of course, significant nonlinguistic differences between regions of the country. Reflecting these regional differences, the settings for most conversations are Beijing and Taipei.

This course represents a new approach to the teaching of foreign languages. In many ways it redefines the roles of teacher and student, of classwork and homework, and of text and tape. Here is what you should expect:

The focus is on communicating in Chinese in practical situations—the obvious ones you will encounter upon arriving in China. You will be communicating in Chinese most of the time you are in class. You will not always be talking about real situations, but you will almost always be purposefully exchanging information in Chinese.

This focus on conimunicating means that the teacher is first of all your conversational partner. Anything that forces him1 back into the traditional roles of lecturer and drillmaster limits your opportunity to interact with a speaker of the Chinese language and to experience the language in its full spontaneity, flexibility, and responsiveness.

Using class time for communicating, you will complete other course activities out of class whenever possible. This is what the tapes are for. They introduce the new material of each unit and give you as much additional practice as possible without a conversational partner.

The texts summarize and supplement the tapes, which take you through new material step by step and then give you intensive practice on what you have covered. In this course you will spend almost all your time listening to Chinese and saying things in Chinese, either with the tapes or in class.

How the Course Is Organized

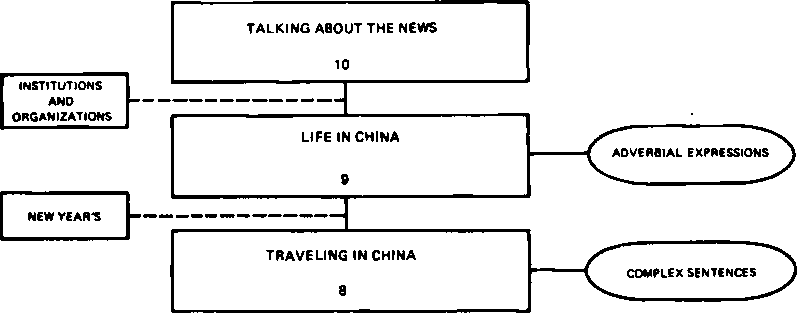

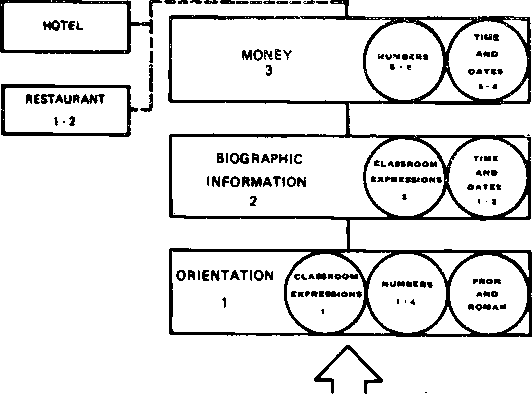

The subtitle of this course, "A Modular Approach,” refers to overall organization of the materials into MODULES which focus on particular situations or language topics and which allow a certain amount of choice as to what is taught and in what order. To highlight equally significant features of the course, the subtitle could just as well have been "A Situational Approach," "A Taped-Input Approach," or "A Communicative Approach."

Ten situational modules form the

ORIENTATION (ORN)

BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION (BIO)

MONEY (MON)

DIRECTIONS (DIR)

TRANSPORTATION (TRN)

ARRANGING A MEETING (MTG)

SOCIETY (SOC)

TRAVELING IN CHINA (TRL)

LIFE IN CHINA (LIC)

TALKING ABOUT THE NEWS (TAN)

Each core module consists of tapes,

core of the course:

Talking about who you are and where you are from.

Talking about your background, family, studies, and occupation and about your visit to China.

Making purchases and changing money.

Asking directions in a city or in a building.

Taking buses, taxis, trains, and planes, including finding out schedule information, buying tickets, and making reservations.

Arranging a business meeting or a social get-together, changing the time of an appointment, and declining an invitation.

Talking about families, relationships between people, cultural roles in traditional society, and cultural trends in modern society.

Making travel arrangements and visiting a kindergarten, the Great Wall, the Ming Tombs, a commune, and a factory.

Talking about daily life in Beijing street committees, leisure activities, traffic and transportation, buying and rationing, housing.

Talking about government and party policy changes described in newspapers: the educational system,-agricultural policy, international policy, ideological policy, and policy in the arts.

student textbook, and a workbook.

In addition to the ten CORE modules, there are also RESOURCE modules and OPTIONAL modules’. Resource modules teach particular systems in the language, such as numbers and dates. As you proceed through a situational core module, you will occasionally take time out to study part of a resource module. (You will begin the first’ three of these while studying the Orientation Module.)

PRONUNCIATION AND ROMANIZATION (P&R) The sound system of Chinese and the Pinyin system of romanization.

NUMBERS (NUM) Numbers up to five digits.

CLASSROOM EXPRESSIONS (CE) Expressions basic to the classroom

learning situation.

TIME AND DATES (T&D) Dates, days of the week, clock time,

parts of the day.

GRAMMAR Aspect and verb types, word order,

multisyllabic verbs and bǎ, auxiliary verbs, complex sentences, adverbial expressions.

Each module consists of tapes and a student textbook.

The eight optional modules focus on particular situations:

RESTAURANT (RST)

HOTEL (HTL)

PERSONAL WELFARE (WLF)

POST OFFICE AND TELEPHONE (PST/TEL)

CAR (CAR)

CUSTOMS SURROUNDING MARRIAGE, BIRTH, AND DEATH (MBD)

NEW YEAR’S CELEBRATION (NYR)

INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS (l&O)

Each module consists of tapes and a student textbook. These optional modules may be used at any time after certain core modules.

The diagram on page shows how the core modules, optional modules, and resource modules fit together in the course. Resource modules are shown where study should begin. Optional modules are shown where they may be introduced.

STANDARD CHINESE : A MODULAR APPROACH

KEY

Inside a Core Module

Each core module has from four to eight units. A module also includes

Objectives: The module objectives are listed at the beginning of the text for each module. Read these before starting work on the first unit to fix in your mind what you are trying to accomplish and what you will have to do to pass the test at the end of the module.

Target Lists: These follow the objectives in the text. They summarize the language content of each unit in the form of typical questions and answers on the topic of that unit. Each sentence is given both in roman-ized Chinese and in English. Turn to the appropriate Target List before, during, or after your work on a unit, whenever you need to pull together what is in the unit.

Review Tapes (R-l): The Target List sentences are given on these tapes. Except in the short Orientation Module, there are two R-l tapes for each module.

Criterion Test: After studying each module, you will take a Criterion Test to find out which module objectives you have met and which you need to work on before beginning to study another module.

Inside a Unit

Here is what you will be doing in each unit. First, you will work through two tapes:

1. Comprehension Tape 1 (C-l): This tape introduces all the new words and structures in the unit and lets you hear them in the context of short conversational exchanges. It then works them into other short conversations and longer passages for listening practice, and finally reviews them in the Target List sentences. Your goal when using the tape is to understand all the Target List sentences for the unit.

2. Production Tape 1 (P-1): This tape gives you practice in pronouncing the new words and in saying the sentences you learned to understand on the C-l tape. Your goal when using the P-1 tape is to be able to produce any of the Target List sentences in Chinee? when given the English equivalent.

The C-l and P-1 tapes, not accompanied by workbooks, are "portable" in the sense that they do not tie you down to your desk. However, there are some written materials for each unit which you will need to work into your study routine. A text Reference List at the beginning of each unit contains the sentences from the C-l and P-1 tapes. It includes both the Chinese sentences and their English equivalents. The text Reference Notes restate and expand the comments made on the C-l and P-1 tapes concerning grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and culture.

After you have worked with the C-l and P-1 tapes, you go on to two class activities:

3. Target List Review: In this first class activity of the unit, you find out how well you learned the C-l and P-1 sentences. The teacher checks your understanding and production of the Target List sentences. He also presents any additional required vocabulary items, found at the end of the Target List, which were not on the C-l and P-1 tapes.

U. Structural Buildup: During this class activity, you work on your understanding and control of the new structures in the unit. You respond to questions from your teacher about situations illustrated on a chalkboard or explained in other ways.

After these activities, your teacher may want you to spend some time working on the drills for the unit.

5. Drill Tape: This tape takes you through various types of drills based on the Target List sentences and on the additional required vocabulary.

6. Drills: The teacher may have you go over some or all of the drills in class, either to prepare for work with the tape, to review the tape, or to replace it.

Next, you use two more tapes. These tapes will give you as much additional practice as possible outside of class.

7. Comprehension Tape 2 (C-2): This tape provides advanced listening practice with exercises containing long, varied passages which fully exploit the possibilities of the material covered. In the C-2 Workbook you answer questions about the passages.

8. Production Tape 2 (P-2): This tape resembles the Structural Buildup in that you practice using the new structures of the unit in various situations. The P-2 Workbook provides instructions and displays of information for each exercise.

Following work on these two tapes, you take part in two class activities:

9. Exercise Review: The teacher reviews the exercises of the C-2 tape by reading or playing passages from the tape and questioning you on them. He reviews the exercises of the P-2 tape by questioning you on information displays in the P-2 Workbook.

10. Communication Activities: Here you use what you have learned in the unit for the purposeful exchange of information. Both fictitious situations (in Communication Games) and real-world situations involving you and your classmates (in "interviews”) are used.

Materials and Activities for a Unit

TAPED MATERIALS

C-l, P-1 Tapes

WRITTEN MATERIALS

Target List Reference List Reference Notes

D-l Tapes

C-2, P-2 Tapes

Drills

Reference Notes C-2, P-2 Workbooks

CLASS ACTIVITIES

Target List Review

Structural Buildup Drills

Exercise Review

Communication Activities

Wen wǔ Temple in central Taiwan (courtesy of Thomas Madden)

The Chinese Languages

We find it perfectly natural to talk about a language called ’’Chinese. ’’ We say, for example, that the people of China speak different dialects of Chinese, and that Confucius wrote in an ancient form of Chinese. On the other hand, we would never think of saying that the people of Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal speak dialects of one language, and that Julius Caesar wrote in an ancient form of that language. But the facts are almost exactly parallel.

Therefore, in terms of what we think of as a language when closer to home, ’’Chinese” is not one language, but a family of languages. The language of Confucius is partway up the trunk of the family tree. Like Latin, it lived on as a literary language long after its death as a spoken language in popular use. The seven modern languages of China, traditionally known as the "dialects," are the branches of the tree. They share as strong a family resemblance as do Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese, and are about as different from one another.

The predominant language of China is now known as Putonghua, or "Standard Chinese" (literally "the common speech"). The more traditional term, still used in Taiwan, is Guoyǔ, or "Mandarin" (literally "the national language"). Standard Chinese is spoken natively by almost two-thirds of the population of China and throughout the greater part of the country.

The term "Standard Chinese" is often used more narrowly to refer to the true national language which is emerging. This language, which is already the language of all national broadcasting, is based primarily on the 'Peking dialect, but takes in elements from other dialects of Standard Chinese and even from other Chinese languages. Like many national languages, it is more widely understood than spoken, and is often spoken with some concessions to local speech, particularly in pronunciation.

The Chinese languages and their dialects differ far more in pronunciation than in grammar and vocabulary. What distinguishes Standard Chinese most from the other Chinese languages, for example, is that it has the fewest tones and the fewest final consonants.

The remaining six Chinese languages, spoken by approximately a quarter of the population of China, are tightly grouped in the southeast, below the Yangtze River. The six are: the Wu group (Wu), which includes the "Shanghai dialect"; Hunanese (Xiāng); the "Kiangsi dialect" (Gan); Cantonese (Yuè), the language of Guāngdōng, widely spoken in Chinese communities in the United States; Fukienese (Min), a variant of which is spoken by a majority on Taiwan and hence called Taiwanese; and Hakka (Kèjiā). spoken in a belt above the Cantonese area, as well as by a minority on Taiwan. Cantonese, Fukienese, and Hakka are also widely spoken throughout Southeast Asia.

There are minority ethnic groups in China who speak non-Chinese languages. Some of these, such as Tibetan, are distantly related to the Chinese languages. Others, such as Mongolian, are entirely unrelated.

Some Characteristics of Chinese

To us, perhaps the most striking feature of spoken Chinese is the use of variation in tone ("tones") to distinguish the different meanings of syllables which would otherwise sound alike. All languages, and Chinese is no exception, make use of sentence intonation to indicate how whole sentences are to be understood. In English, for example, the rising pattern in "He’s gone?" tells us that the sentence is meant as a question. The Chinese tones, however, are quite a different matter. They belong to individual syllables, not to the sentence as a whole. An inherent part of each Standard Chinese syllable is one of four distinctive tones. The tone does just as much to distinguish the syllable as do the consonants and vowels. For example, the only difference between the verb "to buy," m&i, and the verb "to sell," mài, is the Low tone (w) and the Falling tone (-). And yet these words are just as distinguishable as our words "buy" and "guy," or "buy" and "boy." Apart from the tones, the sound system of Standard Chinese is no more different from English than French is.

Word formation in Standard Chinese is relatively simple. For one thing, there are no conjugations such as are found in many European languages. Chinese verbs have fewer forms than English verbs, and nowhere near as many irregularities. Chinese grammar relies heavily on word order and often the word order is the same as in English. For these reasons Chinese is not as difficult for Americans to learn to speak as one might think.

It is often said that Chinese is a monosyllabic language. This notion contains a good deal of truth. It has been found that, on the average, every other word in ordinary conversation is a single-syllable word. Moreover, although most words in the dictionary have two syllables, and some have more, these words can almost always be broken down into singlesyllable units of meaning, many of which can stand alone as words.

Written Chinese

Most languages with which we are familiar are written with an alphabet. The letters may be different from ours, as in the Greek alphabet, but the principle is the same: one letter for each consonant or vowel sound, more or less. Chinese, however, is written with "characters" which stand for whole syllables—in fact, for whole syllables with particular meanings. Although there are only about thirteen hundred phonetically distitìct syllables in standard Chinese, there are several thousand Chinese characters in everyday use, essentially one for each single-syllable unit of meaning. This means that many words have the same pronunciation but are written with different characters, as tiān, "sky," X, and tiān, "to add," "to increase,"

Chinese characters are often referred to as "ideographs," which suggests that they stand directly for ideas. But this is misleading. It is better to think of them as standing for the meaningful syllables of the spoken language.

Minimal literacy in Chinese calls for knowing about a thousand characters. These thousand characters, in combination, give a reading vocabulary of several thousand words. Full literacy calls for knowing some three thousand characters. In order to reduce the amount of time needed to learn characters, there has been a vast extension in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) of the principle of character simplification, which has reduced the average number of strokes per character by half.

During the past century, various systems have been proposed for representing the sounds of Chinese with letters of the Roman alphabet. One of these romanizations, Hànyu Pinyin (literally "Chinese Language Spelling," generally called "Pinyin" in English), has been adopted officially in the PRC, with the short-term goal of teaching all students the Standard Chinese pronunciation of characters. A long-range goal is the use of Pinyin for written communication throughout the country. This is not possible, of course, until speakers across the nation have uniform pronunciations of Standard Chinese. For the time being, characters, which represent meaning, not pronunciation, are still the most widely accepted way of communicating in writing.

Pinyin uses all of the letters in our alphabet except v, and adds the letter u. The spellings of some of the consonant sounds are rather arbitrary from our point of view, but for every consonant sound there is only one letter or one combination of letters, and vice versa. You will find that each vowel letter can stand for different vowel sounds, depending on what letters precede or follow it in the syllable. The four tones are indicated by accent marks over the vowels, and the Neutral tone by the absence of an accent mark:

One reason often given for the retention of characters is that they can be read, with the local pronunciation, by speakers of all the Chinese languages. Probably a stronger reason for retaining them is that the characters help keep alive distinctions of meaning between words, and connections of meaning between words, which are fading in the spoken language. On the other hand, a Cantonese could learn to speak Standard Chinese, and read it alphabetically, at least as easily as he can learn several thousand characters.

Pinyin is used throughout this course to provide a simple written representation of pronunciation. The characters, which are chiefly responsible for the reputation of Chinese as a difficult language, are taught separately.

Each Chinese character is written as a fixed sequence of strokes. There are very few basic types of strokes, each with its own prescribed direction, length, and contour. The dynamics of these strokes as written with a brush, the classical writing instrument, show up clearly even in printed characters. You can tell from the varying thickness of the stroke how the brush met the paper, how it swooped, and how it lifted; these effects are largely lost in characters written with a ball-point pen.

The sequence of strokes is of particular importance. Let’s take the character for "mouth," pronounced kou. Here it is as normally written, with the order and directions of the strokes indicated.

If the character is written rapidly, in "running-style writing," one stroke glides into the next, like this.

If the strokes were written in any but the proper order, quite different distortions would take place as each stroke reflected the last and anticipated the next, and the character would be illegible.

The earliest surviving Chinese characters, inscribed on the Shang Dynasty "oracle bones" of about 1500 B.C., already included characters that went beyond simple pictorial representation. There are some characters in use today which are pictorial, like the character for "mouth." There are also some which are directly symbolic, like our Roman numerals I, II, and III. (The characters for these numbers—the first numbers you learn in this course—are like the Roman numerals turned on their sides.) There are some which are indirectly symbolic, like our Arabic numerals 1, 2, and 3. But the most common type of character is complex, consisting of two parts: a "phonetic," which suggests the pronunciation, and a "radical," which broadly characterizes the meaning. Let’s take the following character as an example.

This character means "ocean" and is pronounced yang. The left side of the character, the three short strokes, is an abbreviation of a character which means "water" and is pronounced shul. This is the "radical." It has been borrowed only for its meaning, "water." The right side of the character above is a character which means "sheep" and is pronounced yang. This is the "phonetic." It has been borrowed only for its sound value, yang. A speaker of Chinese encountering the above character for the first time could probably figure out that the only Chinese word that sounds like yang and means something like "water" is the word yang meaning "ocean." We, as speakers of English, might not be able to figure it out. Moreover, phonetics and radicals seldom work as neatly as in this example. But we can still learn to make good use of these hints at sound and sense.

Many dictionaries classify characters in terms of the radicals. According to one of the two dictionary systems used, there are 1?6 radicals; in the other system, there are 21U. There are over a thousand phonetics.

Chinese has traditionally been written vertically, from top to bottom of the page, starting on the right-hand side, with the pages bound so that the first page is where we would expect the last page to be. Nowadays, however, many Chinese publications paginate like Western publications, and the characters are written horizontally, from left to right.

A Chinese personal name consists of two parts: a surname and a given name. There is no middle name. The order is the reverse of ours: surname first, given name last.

The most common pattern for Chinese names is a single-syllable surname followed by a two-syllable given name:2

Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung)

Zhōu Ēnlái (Chou En-lai)

Jiang Jièshí (Chiang Kai-shek)

Song Qìnglíng (Soong Ch’ing-ling—Mme Sun Yat-sen)

Song Měilíng (Soong Mei-ling—Mme Chiang Kai-shek)

It is not uncommon, however, for the given name to consist of a single syllable:

Zhū De (Chu Teh)

Lin Biāo (Lin Piao)

Hú Shi (Hu Shih)

Jiāng Qīng (Chiang Ch’ing—Mme Mao Tse-tung)

There are a few two-syllable surnames. These are usually followed by single-syllable given names:

Sīmǎ Guāng (Ssu-ma Kuang) Ōuyáng Xiū (Ou-yang Hsiu) ZhūgS Liang (Chu-ke Liang)

But two-syllable surnames may also be followed by two-syllable given names:

Sīmǎ Xiāngrú (Ssu-ma Hsiang-Ju)

An exhaustive list of Chinese surnames includes several hundred written with a single character and several dozen written with two characters. Some single-syllable surnames sound exactly alike although written with different characters, and to distinguish them, the Chinese may occasionally have to describe the character or "write" it with a finger on the palm of a hand. But the surnames that you are likely to encounter are fewer than a hundred, and a handful of these are so common that they account for a good majority of China’s population.

Given names, as opposed to surnames, are not restricted to a limited list of characters. Men's names are often but not always distinguishable from women’s; the difference, however, usually lies in the meaning of the characters and so is not readily apparent to the beginning student with a limited knowledge of characters.

Outside the People’s Republic the traditional system of titles is still in use. These titles closely parallel our own "Mr.," "Mrs.," and "Miss." Notice, however, that all Chinese titles follow the name—either the full name or the surname alone—rather than preceding it.

The title "Mr." is Xiānsheng.

MS Xiānsheng

JIS Mínglī Xiānsheng

The title "Mrs." is Tàitai. It follows the husband’s full name or surname alone.

MS Tàitai

MS Mínglī Tàitai

The title "Miss" is Xiǎojiě. The MS family’s grown daughter, Défēn, would be

MS XiSojiě

Mǎ Défēn XiSojiě

Even traditionally, outside the People’s Republic, a married woman does not take her husband’s name in the same sense as in our culture. If Miss Fāng Bǎolán marries Mr. MS Mínglī, she becomes Mrs. MS Mínglī, but at the same time she remains Fāng BSolán. She does not become MS BSolán; there is no equivalent of "Mrs. Mary Smith." She may, however, add her husband’s surname to her own full name and refer to herself as MS Fāng Bǎolán. At work she is quite likely to continue as Miss Fāng.

These customs regarding names are still observed by many Chinese today in various parts of the world. The titles carry certain connotations, however, when used in the PRC today: Tàitai should not be used because it designates that woman as a member of the leisure class. XiSojiě should not be used because it carries the connotation of being from a rich family.

In the People’s Republic, the title "Comrade," Tóngzhì, is used in place of the titles Xiānsheng, Tàitai, and XiSojiě. MS Mínglī would be

MS Tóngzhì

MS Mínglī Tóngzhì

The title ’’Comrade" is applied to all, regardless of sex or marital status. A married'-woman does not take her husband’s name in any sense. MS Mínglī’s wife would be

Fāng Tóngzhì

Fāng Bǎolán Tóngzhì

Children may be given either the mother’s or the father’s surname at birth. In some families one child has the father's surname, and another child has the mother’s surname. MS Mínglī’s and Fāng Bǎolán*s grown daughter could be

MS Tóngzhì

MS Défēn Tóngzhì

Their grown son could be

Fāng Tóngzhì

Fāng Zìqiáng Tóngzhì

Both in the PRC and elsewhere, of course, there are official titles and titles of respect in addition to the common titles we have discussed here. Several of these will be introduced later in the course.

The question of adapting foreign names to Chinese calls for special consideration. In the People’s Republic the policy is to assign Chinese phonetic equivalents to foreign names. These approximations are often not as close phonetically as they might be, since the choice of appropriate written characters may bring in nonphonetic considerations. (An attempt is usually made when transliterating to use characters with attractive meanings.) For the most part, the resulting names do not at all resemble Chinese names. For example, the official version of "David Anderson" is Dàiwéi Āndésēn.

An older approach, still in use outside the PRC, is to construct a valid Chinese name that suggests the foreign name phonetically. For example, "David Anderson" might be in Dàwèi.

Sometimes, when a foreign surname has the same meaning as a Chinese surname, semantic suggestiveness is chosen over phonetic suggestiveness. For example, Wáng, a common Chinese surname, means "king," so "Daniel King" might be rendered Wáng Dànián.

Students in this course will be given both the official PRC phonetic equivalents of their names and Chinese-style names.

The Orientation Module and associated resource modules provide the linguistic tools needed to begin the study of Chinese. The materials also introduce the teaching procedures used in this course.

The Orientation Module is not a typical course module in several respects. First, it does not have a situational topic of its own, but rather leads into the situational topic of the following module—Biographic Information. Second, it teaches only a little Chinese grammar and vocabulary. Third, two of the associated resource modules (Pronunciation and Romanization, Numbers) are not optional; together with the Orientation Module, they are prerequisite to the rest of the course.

Upon successful completion of this module and the two associated resource modules, the student should

1. Distinguish the sounds and tones of Chinese well enough to be able to write the Hànyǔ Pinyin romanization for a syllable after hearing the syllable.

2. Be able to pronounce any combination of sounds found in the words of the Target Lists when given a romanized syllable to read. (Although the entire sound system of Chinese is introduced in the module, the student is responsible for producing only sounds used in the Target Sentences for ORN. Producing the remaining sounds is included in the Objectives for Biographic Information.)

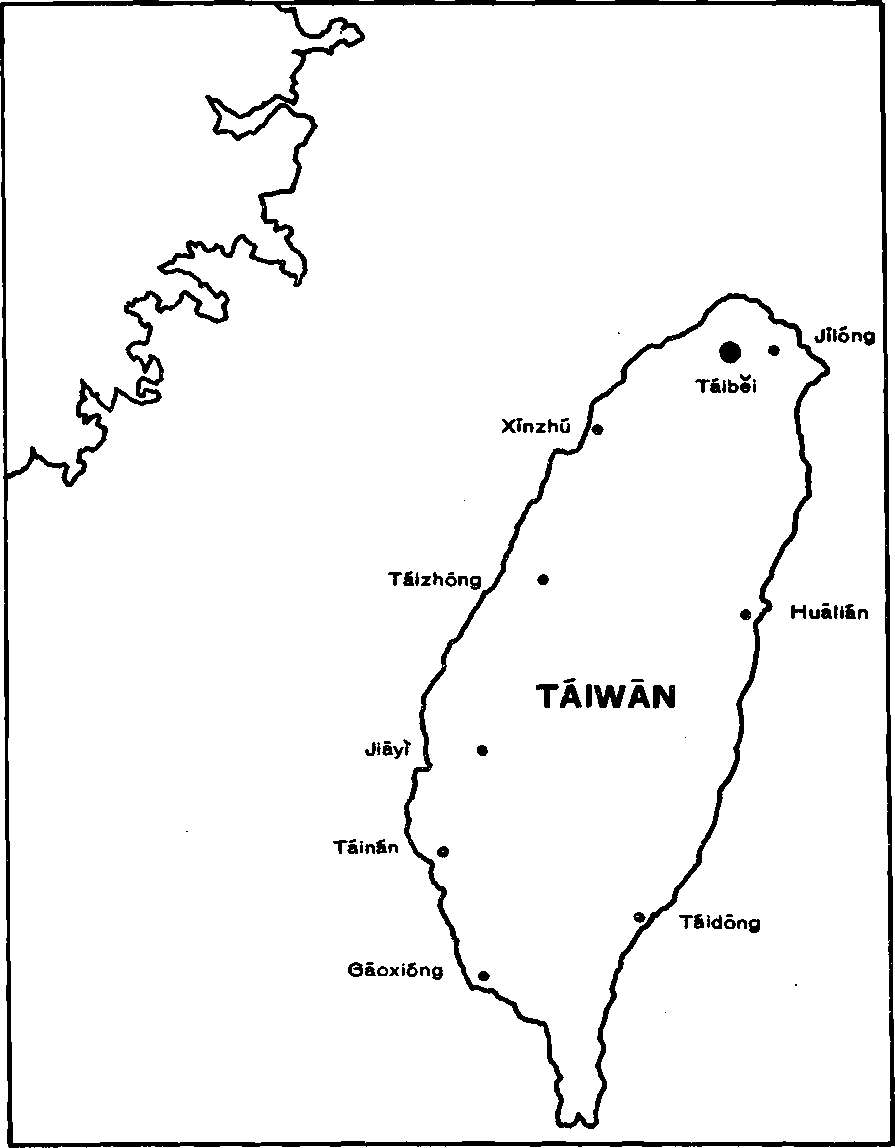

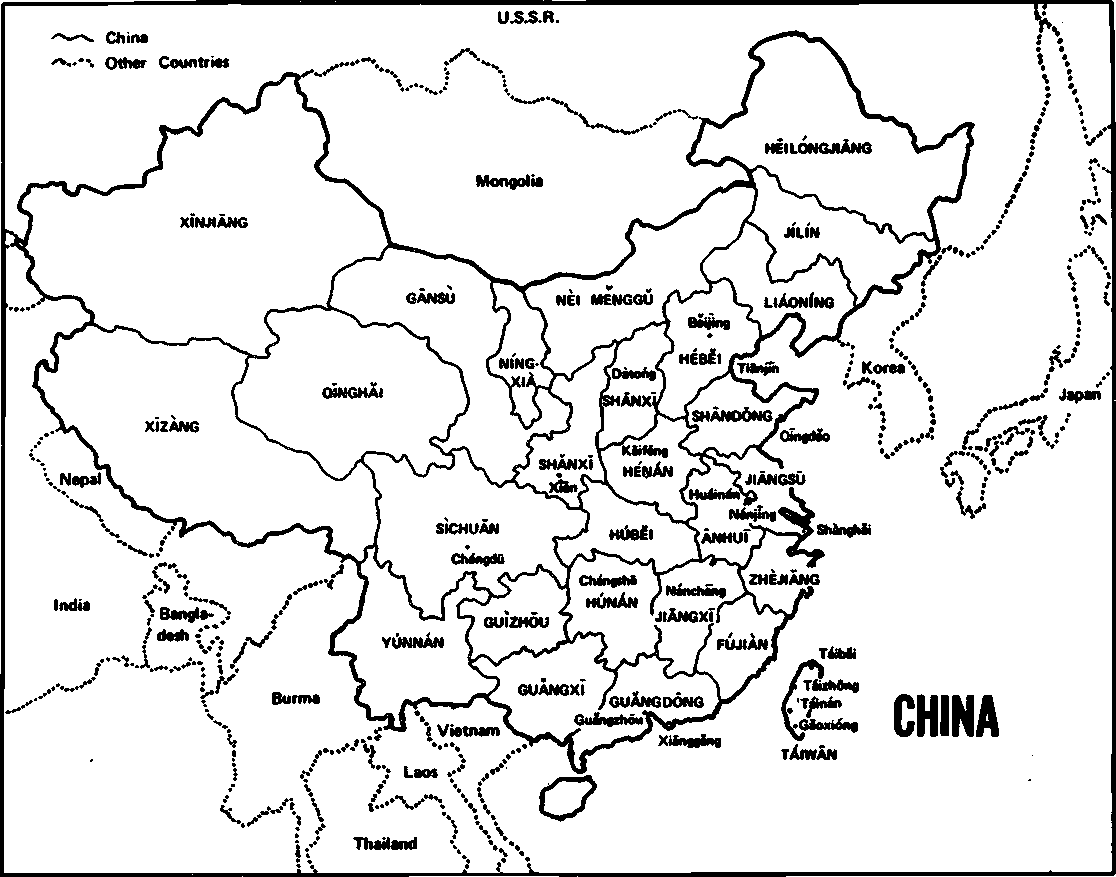

3. Know the names and locations of five cities and five provinces of China well enough to point out their locations on a map, and pronounce the names well enough to be understood by a Chinese.

U. Comprehend the numbers 1 through 99 well enough to write them down when dictated, and be able to say them in Chinese when given English equivalents.

5. Understand the Chinese system of using personal names, including the use of titles equivalent to "Mr.," "Mrs.," "Miss," and "Comrade."

6. Be able to ask. and understand questions about where someone is from.

7. Be able to ask and understand questions about where someone is.

8. Be able to give the English equivalents for all the Chinese expressions in the Target Lists.

9. Be able to say all the Chinese expressions in the Target Lists when cued with English equivalents.1

10. Be able to take part in short Chinese conversations, based on the Target Lists, about how he is, who he is, and where he is from.

Orientation (ORN)

|

Unit 1: Unit 2: |

1 C-l |

1 P-1 | ||

|

2 |

C-l |

2 P-1 |

1&2 D-l | |

|

Unit 3: |

3 |

C-l |

3 P-1 |

3 D-l 3 C-2 3 P-2 |

|

Unit U: |

1» |

C-l |

h P-1 |

h D-l U C-2 U P-2 |

Pronunciation and Romanization (P&R)

|

P&R 1 |

P&R 2 |

P&R 3 |

P&R U |

P&R 5 |

P&R 6 |

Numbers (NUM)

|

NUM 1 NUM 2 |

NUM 3 |

NUM U |

|

Classroom Expressions |

(CE) | |

|

CE 1 |

|

1. |

A: |

NX shi shéi? |

Who are you? |

|

B: |

WS shi Wang Dànián. |

I am Wang Dànián (Daniel King). | |

|

A: |

WS shi Hú Měilíng. |

I am Hú Měilíng. | |

|

2. |

A: |

Nī xìng shénme? |

What is. your surname? |

|

B: |

Wǒ xìng Wáng. |

My surname is Wáng (King). | |

|

A: |

WS xìng Hú. |

My surname is Hú. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Tā shi shéi? |

Who is he/she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglī. |

He is Mǎ Mínglī. | |

|

A: |

Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. MS. | |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Mǎ. | |

|

A: |

Tā shi MS Xiǎojiě. |

She is Miss Mǎ. | |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Tóngzhì. |

He/she is Comrade Mǎ. | |

|

h. |

A: |

Wang Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? |

Mr. Wáng, who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglī Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. Mǎ Mínglī. | |

|

5- |

A: |

Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? |

Sir, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglī Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. Mǎ Mínglī. | |

|

6. |

A: |

Tóngzhì, tā shi shéi? |

Comrade, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fāng Bǎolán Tóngzhì. |

She is Comrade Fāng Bǎolán. |

|

1. A: B: A: |

Nī shi Wáng Xiānsheng ma? W5 shi Wang Dànián. Wǒ bú shi Wáng Xiānsheng. |

Are you Mr. Wáng? I am Wang Dànián. I’m not Mr. Wang. |

|

2. A: |

Nī xìng Wáng ma? |

Is your surname Wáng? |

|

B: |

Wǒ xìng Wáng. |

My surname is Wáng. |

|

A: |

Wo bú xìng Wáng. |

My surname isn't Wang, |

|

3. |

A: B: |

NÍn guìxìng? Wǒ xìng Wang. |

Your surname? (POLITE) My surname is Wang. |

|

U. |

A: |

Nl Jiao shénme? |

What is your given name? |

|

B: |

Wǒ Jiao Dànián. |

My given name is Dànián (Daniel). | |

|

5. |

A: |

Nl hǎo a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

Wǒ hǎo. Nī ne? |

I’m fine. And you? | |

|

A: |

Hǎo. Xièxie. |

Fine, thank you. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

6. míngzi given name

h. A: Nī shi nārde rén? B: Wǒ shi Jiāzhōu rén. B: Wǒ shi Shànghāi rén. |

Are you an American? Yes (I am). No (I'm not). Are you Chinese? Yes, I'm Chinese. No, I'm not Chinese. What's your nationality? I'm an American. I’m Chinese. I'm English. Where are you from? I'm a Californian. I'm from Shanghai. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

|

5. |

Déguo |

Germany |

|

6. |

Eguō (Eguo) |

Russia |

|

7. |

Fàguō (Fāguó) |

France |

|

8. |

Rìběn |

Japan |

1. A: Andésén Xiānsheng, nī shi nārde rén?

B; Wǒ shi Dézhōu rén.

A: Andésén Fūren ne?

B: Tā yě shi Dézhōu rén.

2. A: Tā shi Yīngguo rén ma?

B: Bú shi, tā bú shi Yīngguo rén.

A: Tā àiren ne?

B: Tā yě bú shi Yīngguo rén.

3. A: Qīngwèn, nī lāojiā zài nār?

B: Wǒ lāojiā zài Shāndōng.

U. A: Qīngdāo zài zhèr ma?

B: Qīngdāo bú zài nàr, zài zhèr.

5. A: Nī àiren xiànzài zài nār?

B: Tā xiànzài zài Jiānádà.

Where are you from, Mr. Anderson?

I’m from Texas.

And Mrs. Anderson?

She is from Texas too.

Is he English?

No, he is not English.

And his wife?

She isn’t English either.

May I ask, where is your family from?

My family is from Shāndōng.

Is Qingdāo here? (pointing to a map)

Qīngdāo isn't there; it’s here (pointing to a map;

Where is your spouse now?

He/she is in Canada now.

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY

(not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

6. Learn the pronunciation and .location of any five cities and five provinces of China found on the maps on pages 30-81.

On a Běijīng street (courtesy of Pat Fox)

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Questions and answers about full names and surnames.

2. Titles and terms of address ("Mr.,” "Mrs.," etc.).

Prerequisites to the Unit

(Be sure to complete these before starting the unit.)

1. Background Notes.

2. PiR 1 (Tape 1 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization), the tones.

3. P&R 2 (Tape 2 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization), the tones.

Materials You Will Need 1. The C-l and P-1 tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The drill tape (1D-1).

About the C-l and P-1 Tapes

The C-l and P-1 tapes are your introduction to the Chinese words and structures presented in each unit. The tapes give you explanations and practice on the new material. By the time you have worked through these two tapes, you will be competent in understanding and producing the expressions introduced in the unit.

With the C-l tape, you learn to understand the new words and structures. The material is presented in short conversational exchanges, first with English translations and later with pauses which allow you to translate. Try to give a complete English translation for each Chinese expression. Your goal when using the C-l tape is to learn the meanings of all the words and structures as they are used in the sentences.

With the P-1 tape, you learn to put together these sentences. You learn to pronounce each new word and use each new structure. When the recorded instructions direct you to pronounce a word or say a sentence, do so out loud. It is important fop you to hear yourself speaking Chinese, so that you will know whether you are pronouncing the words correctly. Making the effort to say the expression is a big part of learning it. It is one thing to think about how a sentence should be put together or how it should sound. It is another thing to put it together that way or make it sound that way. Your goal when using the P-1 tape is to produce the Target List expressions in Chinese when given English equivalents. At the end of each P-1 tape is a review of the Target List which you can go over until you have mastered the expressions.

At times, you may feel that the material on a tape is being presented too fast. You may find that there is not enough time allowed for working out the meaning of a sentence or saying a sentence the way you want to. When this happens, stop the tape. If you want to, rewind.' Use the control buttons on your machine to make the tape manageable for you and to get the most out of it.

About the Reference List and the Reference Notes

The Reference List and the Reference Notes are designed to be used before, during, or directly after work with the C-l and P-1 tapes.

The Reference List is a summary of the C-l and P-1 tapes. It contains all sentences which introduce new material, showing you both the Chinese sentences written in romanization and their English equivalents. You will find that the list is printed so that either the Chinese or the English can be covered to allow you to test yourself on comprehension, production, or romanization of the sentences.

The Reference Notes give you information about grammar, pronunciation, and cultural usage. Some of these explanations duplicate what you hear on the C-l and P-1 tapes. Other explanations contain new information.

You may use the Reference List and Reference Notes in various ways. For example, you may follow the Reference Notes as you listen to a tape, glancing at an exchange or stopping to read a comment whenever you want to. Or you may look through the Reference Notes before listening to a tape, and then use the Reference List while you listen, to help you keep track of where you are. Whichever way you decide to use these parts of a unit, remember that they are reference materials. Don’t rely on the translations and romanizations as subtitles for the C-l tape or as cue cards for the P-1 tape, for this would rob you of your chance to develop listening and responding skills.

About the Drills

The drills help you develop fluency, ease of response, and confidence. You can go through the drills on your own, with the drill tapes, and the teacher may take you through them in class as well.

Allow more than half an hour for a half-hour drill tape, since you will usually need to go over all or parts of the tape more than once to get full benefit from it.

The drills include many personal names, providing you with valuable pronunciation practice. However, if you find the names more than you can handle the first time through the tape, replace them with the pronoun tā whenever possible. Similar substitutions are often possible with place names.

Some of the drills involve sentences which you may find too long to understand or produce on your first try, and you will need to rewind for another try. Often, particularly the first time through a tape, you will find the pauses too short, and you will need to stop the tape to give yourself more time. The performance you should aim for with these tapes, however, is full comprehension and full, fluent, and accurate production while the tape rolls.

The five basic types of drills are described below.

Substitution Drills; The teacher (T) gives a pattern sentence which the student (S) repeats. Then the teacher gives a word or phrase (a cue) which the student substitutes appropriately in the original sentence. The teacher follows immediately with a new cue.

Here is an English example of a substitution drill:

T: Are you an American?

S: Are you an American?

T: (cue) English

S: Are you English?

T: (cue) French

S: Are you French?

Transformation Drills: On the basis of a model provided at the beginning of the drill, the student makes a certain change in each sentence the teacher says.

Here is an English example of a transformation drill, in which the student is changing affirmative sentences into negative ones: '

T: I’m going to the bank.

S: I’m not going to the bank.

T: I’m going to the store.

S: I’m not going to the store.

Response Drills: On the basis of a model given at the beginning of the drill, the student responds to questions or remarks by the teacher as cued by the teacher.

Here is an English example of-a response drill:

T: What is his name? (cue) Harris

S: His name is Harris.

T: What is her name? (cue) Noss

S: Her name is Noss.

Expansion Drills: The student adds something to a pattern sentence as cued by the teacher.

Here is an English example of an expansion drill

(cue) Japanese He's Japanese.

(cue) French She's French.

T: He isn’t Chinese. S: He isn't Chinese. T: She isn’t German. S: She isn’t German.

Combination Drills: On the basis of a model given at the beginning of the drill, the student combines two phrases or sentences given by the teacher into a single utterance.

Here is an English example of a combination drill:

T: I am reading a book. John gave me the book.

S: I am reading a book which John gave me.

T: Mary bought a picture. I like the picture.

S: Mary bought a picture which I like.

|

1. |

A: B: |

Nī shi shéi? W3 shi Wáng Dànián. |

Who are you? I am Wang Danián. |

|

2. |

A: B: |

NX shi shéi? W8 shi Hú Měilíng. |

Who are you? I am Hu Měilíng. |

|

3. |

A: B: |

Tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Mínglī. |

Who is he? He is MS Mínglī. |

|

U. |

A: B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglī. Tā shi Hú Měilíng. |

He is Mǎ Mínglī. She is Hu Měilíng. |

|

5- |

A: B: |

Nī xìng shénme? W8 xìng Wáng. |

What is your surname? My surname is Wang. |

|

6. |

A: B: |

Tā xìng shénme? Tā xìng MS. |

What is his surname? His surname is Mǎ. |

|

7. |

A: B: |

Tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. |

Who is he? He is Mr. Ma. |

|

8. |

A: B: |

Tā shi shéi? Tā shi Mǎ Mínglī Xiānsheng. |

Who is he? He is Mr. Mǎ Mínglī. |

|

9. |

A: |

Wáng Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? |

Mr. Wáng, who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Mínglī Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. MS Mínglī. | |

|

10. |

A: B: |

Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. |

Sir, who is he? He is Mr. MS. |

|

11. |

A: B: |

Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Tàitai. |

Sir, who is she? She is Mrs. Ma. |

|

12. |

A: B: |

Wáng Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Mínglī Tàitai. |

Mr. Wáng, who is she? She is Mrs. MS Mínglī. |

|

13. |

A: B: |

Wáng Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Xiǎojiě. |

Mr. Wang, who is she? She is Miss Mǎ. |

|

1U. |

A: B: |

Tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Mínglī Tongzhì. |

Who is he? He is Comrade Mǎ Mínglī. |

15. A: Tóngzhì, tā shi shéi? Comrade, who is she?

B: Tā shi Fāng Bǎolán. She is Fang Bǎolán.

16. A: Tóngzhì, tā shi shéi? Comrade, who is she?

B: Tā shi Fāng Bǎolán Tóngzhì. She is Comrade Fāng Bǎolán.

|

nl |

you |

|

shéi |

who |

|

shénme |

what |

|

shì |

to be |

|

tā |

he, she |

|

tàitai |

Mrs. |

|

tóngzhì |

Comrade |

|

wS |

I |

|

xiānsheng |

Mr.; sir |

|

xiǎojiǎ (xiáojie) |

Miss |

|

xìng |

to be sumamed |

|

1. |

A: B: |

NX shi shéi? WS shi Wang Dànián. |

Who are you? I am Wang Dànián. |

|

2. |

A: |

NX shi shéi? |

Who are you? |

|

B: |

W5 shi Hú MSilíng. |

I am Hú MSilíng. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Tā shi shéi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS MínglX. |

He is MS MínglX. | |

|

U. |

A: |

Tā shi MS MínglX. |

He is MS Míngll. |

|

B: |

Tā shi Hú MSilíng. |

She is Hú MSilíng. |

Notes on Nos. 1-b

The verb shi means "to be" in the sense of "to be someone or something," as in "I am Daniel King." It expresses identity. (In Unit U you will learn a verb which means "to be" in another sense, "to be somewhere," as in "I am in BSijīng." That verb expresses location.) The verb shi is in the Neutral tone (with no accent mark) except when emphasized.

Unlike verbs in European languages, Chinese verbs do not distinguish first, second, and third persons. A single form serves for all three persons.

|

W8 |

shi |

Wáng Dànián. |

(I am Wang Dànián.) |

|

NX |

shi |

Hú MSilíng. |

(You are Hú MSilíng.) |

|

Tā |

shi |

MS Míngll. |

(He is MS MínglX.) |

Later you will find that Chinese verbs do not distinguish singular and plural, either, and that they dó not distinguish past, present, and future as such. You need to learn only one form for each verb.

The pronoun tā is equivalent to both "he" and "she."

The question NX shi shéi? is actually too direct for most situations, although it is all right from teacher to student or from student to student. (A more polite question is introduced in Unit 2.)

Unlike English, Chinese uses the same word order in questions as in statements.

|

Tā |

shi |

shéi? |

(Who is he?) |

|

Tā |

shi |

MS Mínglī? |

(He is Mǎ Mínglī.) |

When you answer a question containing a question word like shéi. "who,” simply replace the question word with the information it asks for.

5. A: NX xìng shénme?

B: Wǒ xìng Wáng.

6. a: Tā xìng shénme?

B: Tā xìng MS.

What is your surname? My surname is Wang.

What is his surname? His surname is Mǎ.

■Notes on Nos. 5-6

Xìng is a verb, "to be surnamed.” It is in the same position in the sentence as shi, "to be."

|

Wǒ |

shi |

Wang Dànián. |

|

(I |

am |

Wáng Dànián.) |

|

Wǒ |

xìng |

Wáng. |

|

(I |

am surnamed |

Wang.) |

Notice that the question word shénme. "what," takes the same position as the question word shéi, "who."

|

Nī |

shi |

shéi? |

|

(You |

are |

who?) |

|

Nī |

xìng |

shénme? |

|

(You |

are surnamed |

what?) |

Shénme is the official spelling. However, the word is pronounced as if it were spelled shémma, or even shéma (often with a single rise in pitch extending over "both syllables'^ Before another word which begins with a consonant sound, it is usually pronounced as if it were spelled shěm.

|

7. |

A: B: |

Tā shi shéi? Tā shi Mǎ Xiānsheng. |

Who is he? He is Mr. Mǎ. |

|

8. |

A: |

Tā shi shéi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Mǎ Mínglī Xiānsheng. |

He is Mr. Ma MÍnglī |

Notes on Nos. 7-8

After the verb shì you may have the full name alone, the surname plus title, or the full name plus title.

|

Tā |

shi |

Mǎ |

Mínglī. | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Mǎ |

Xiānsheng. | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Mǎ |

Mínglī |

Xiānsheng. |

Xiānsheng. literally ’’first-born," has more of a connotation of respectfulness than "Mr." Xiānsheng is usually applied only to people other than oneself. Do not use the title Xiānsheng (or any other respectful title, such as Jiàoshòu, "Professor") when giving your own name. If you want to say "I am Mr. Jones," you may say W5 xìng Jones.

When a name and title are said together, logically enough it is the name which gets the heavy stress: WANG Xiānsheng. You will often hear the title pronounced with no full tones: WĀNG Xiansheng.

9. A: Wang Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi?

Mr. Wang, who is he? He is Mr. Mǎ Mínglī.

Sir, who is he? He is Mr. Ma.

B: Tā shi Mǎ Mínglī Xiānsheng.

10. A: Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? B: Tā shi Mǎ Xiānsheng.

|

11. |

A: B: |

Xiānsheng,- tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS Tàitai. |

Sir, who is she? She is Mrs. MS. |

|

12. |

A: |

Wáng Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? |

Mr. Wang, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Míngll Tàitai. |

She is Mrs. MS Míngll. |

Note on Nos. 9-12

When you address someone directly, use either the name plus the title or the title alone. Xiānsheng must be translated as "sir" when it is used alone, since "Mr." would not capture its respectful tone. (Tàitai, however, is less respectful when used alone. You should address Mrs. MS as MS TÌitai.)

|

13. |

A: B: |

Wáng Xiānsheng, tā shi shéi? Tā shi MS XiSojiS. |

Mr. Wang, who is she? She is Miss MS. |

|

Ih. |

A: |

Tā shi shéi? |

Who is he? |

|

B: |

Tā shi MS Míngll Tóngzhì. |

He is Comrade Mǎ Míngll. | |

|

15. |

A: |

Tóngzhì, tā shi shéi? |

Comrade, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fāng Baolán. |

She is Fāng Baolan. | |

|

16. |

A: |

Tóngzhì, tā shi shéi? |

Comrade, who is she? |

|

B: |

Tā shi Fāng BSolán Tóngzhì. |

She is Comrade Fāng Baolan. |

Note on Nos. 13-16

See the Background Notes on Chinese Personal Names and Titles for Tóngzhì, "Comrade," and the use of maiden names.

A. Substitution Drill

1. Speaker: MS Mínglī

2. Hú Měilíng

3. Wang Dànián

U. Li Shìmín

5. Liú Lìróng

6. Zhāng Bǎolán.

You: Tā shi MS Mínglī.

(He is Mǎ Mínglī.)

Tā shi Hú MSilíng. (She is Hu Meiling.)

Tā shi Wáng Dànián.

(He is Wang Dànián.)

Tā shi LI Shìmín.

(He is Li Shìmín.)

Tā shi Liú Lìróng. (She is Liú Lìróng.)

Tā shi Zhāng Bǎolán.

(She is Zhāng BSolán.)

B. Response Drill

When the cue is given by a male speaker, male students should respond.

When the cue is given by a female speaker, female students should respond.

1. Speaker: Nī shi shéi?

(cue) Wáng Dànián (Who are you?)

OR Nī shi shéi?

(cue) Hú MSilíng

(Who are you?)

2. Nī shi shéi? Liú Shìmín (Who are you?)

3. Nī shi shéi? Chén Huìrán (Who are you?)

k. Nī shi shéi? Huáng Déxián (Who are you?)

5. Nī shi shéi? Zhào Wǎnrú (Who are you?)

You: Wǒ shi Wáng Dànián. (I am Wang Dànián.)

Wǒ shi Hú Měilíng. (I am Hú Měilíng.)

|

Wǒ shi Liú Shìmín. (I am Liú Shìmín.) | ||

|

Wǒ |

shi |

Chén Huìrán. |

|

(I |

am |

Chén Huìrán.) |

|

Wǒ |

shi |

Huáng Déxián. |

|

(I |

am |

Huáng Déxián.) |

|

Wǒ |

shi |

Zhào Wǎnrú. |

|

(I |

am |

Zhào Wǎnrú.) |

6. Nl shi shéi? Jiang Bīngyíng (Who are you?)

7. Nī shi shéi? Gāo Yǒngpíng (Who are you?)

C. Response Drill

1. Speaker: Tā shi shéi?

(cue) MS Xiānsheng

(Who is he?)

Wǒ shi Jiang Bīngyíng. (I am Jiang Bīngyíng.)

Wǒ shi Gāo Yǒngpíng. (I am Gāo Yǒngpíng.)

You: Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. (He is Mr. MS.)

|

2. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is she?) |

Hú Tàitai |

Tā shi Hú Tàitai. (She is Mrs. Hú.) |

|

3. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is he?) |

Máo Xiānsheng |

Tā shi Máo Xiānsheng. (He is Mr. Máo.) |

|

U. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is he?) |

Zhāng Tongzhì |

Tā shi Zhāng Tóngzhì. (He is Comrade Zhāng.) |

|

5. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is she?) |

Liú XiSojiS |

Tā shi Liú XiSojiS. (She is Miss Liú.) |

|

6. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is he?) |

MS Xiānsheng |

Tā shi MS Xiānsheng. (He is Mr. Mǎ.) |

|

7. |

Tā shi shéi? (Who is she?) |

Zhào Tàitai |

Tā shi Zhào Tàitai. (She is Mrs. Zhàò.) |

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Questions and answers about given names.

2. Yes/no questions.

3. Negative statements.

U. Greetings.

Prerequisites to the Unit

1. P&R 3 and P&R U (Tapes 3 and U of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization).

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-1 tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The 2D-1 tape.

|

1. |

A: B: |

Tā shi Wáng Tàitai ma? Tā shi Wáng Tàitai. |

Ib she Mrs. Wang? She is Mrs. Wang. |

|

2. |

A: |

Nī shi Wáng Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Wang? |

|

B: |

WS shi Wáng Dànián. |

I am Wang Dànián. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Nī shi Mā Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Mǎ? |

|

B: |

WS shi Wáng Dànián. |

I am Wáng Dànián. | |

|

U. |

A: |

Nī shi Mǎ Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Mǎ? |

|

B: |

WS bú shi MS Xiānsheng. |

I’m not Mr. Mǎ. | |

|

5. |

A: |

WS shi Wáng Dànián. |

I am Wáng Danián. |

|

B: |

WS bú shi Wáng Dànián. |

I'm not Wáng Dànián. | |

|

6. |

A: |

Ní xìng Fāng ma? |

Is your surname Fāng? |

|

B: |

WS bú xìng Fāng. |

My surname isn’t Fāng. | |

|

7. |

A: |

WS xìng Wáng. |

My surname is Wáng. |

|

B: |

WS bú xìng Wáng. |

My surname isn't Wáng. | |

|

8. |

A: |

Nī xìng MS ma? |

Is your surname Mǎ? |

|

B: |

Bú xìng MS. Xìng Wáng. |

My surname isn't Mǎ. It's Wáng. | |

|

9. |

A: |

Nín guìxìng? |

Your surname? (POLITE) |

|

B: |

WS xìng Wáng. |

My surname is Wáng. | |

|

10. |

A: |

Nī jiào shénme? |

What is your given name? |

|

B: |

WS jiào Dànián. |

My given name is Dànián. | |

|

11. |

A: |

Nī hSo a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

WS hSo. |

I'm fine. | |

|

12. |

A: |

Nī hSo a? |

How are you? |

|

B: |

WS hSo. Nī ne? |

I'm fine. And you? | |

|

A: |

HSo, xièxie. |

Fine, thanks. |

ADDITIONAL REQUIRED VOCABULARY (not presented on C-l and P-1 tapes)

13* míngzi

given name

|

VOCABULARY | |

|

a |

(question marker) |

|

bù/bú bú shi |

not not to be |

|

guìxìng |

(honorable) surname |

|

hSo |

to be fine, to be well |

|

Jiào |

to be called |

|

ma míngzi |

(question marker) given name |

|

ne |

(question marker) |

|

xièxie |

thank you |

|

1. |

At B: |

Tā shi Wáng Tàitai ma? Tā shi Wáng Tàitai. |

Is she Mrs. Wang? She is Mrs. Wáng. |

|

2. |

A: |

Nī shi Wáng Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Wang? |

|

B: |

WS shi Wáng Dànián. |

I am Wang Dànián. | |

|

3. |

A: |

Nī shi Mǎ Xiānsheng ma? |

Are you Mr. Mǎ? |

|

B: |

Wǒ shi Wáng Dànián. |

I am Wáng Dànián. |

Notes cn Nos. 1-3

".he marker ma may be added to any which may be answered ’’yes’’ or ’’no.’’

statement to turn it into a question

|

Tā |

shi |

Wáng Tàitai. |

(She is Mrs. Wáng.) | |

|

Tā |

shi |

Wáng Tàitai |

ma? |

(Is she Mrs. Wáng?) |

The reply to a yes/no question is commonly a complete affirmative or negative statement, although, as you will see later, the statement may be stripped down considerably.

h. A: Nī shi Mǎ Xiānsheng ma?

Are you Mr. Mǎ? I'm not Mr. Ma.

I am Wang Dànián.

I'm not Wang Dànián.

B: WS bú shi MS Xiānsheng.

5. A: WS shi Wang Dànián.

B: Wǒ bú shi Wang Dànián.

Notes on Nos,

The negative of the verb shì, ’’to be,’’ is bú shi, ’’not to be.’’ The equivalent of "not" is the syllable bù. The tone for the syllable bù depends on the tone of the following syllable. When followed by a syllable with a High, Rising, or Low tone, a Falling tone is used (bù). When followed by a syllable with a Falling or Neutral tone, a Rising tone is used (bú).

bù fēi (not to fly) bù féi (not to be fat) bù féi (not to slander) bú fèi (not to waste)

Almost all of the first few verbs you learn happen to be in the Falling tone, and so take bú. But remember that bù is the basic form. That is the form the syllable takes when it stands alone as a short "no” answer—Bù— and when it is discussed, as in "Bù means 'not'.”

Notice that even though shi, "to be,” is usually pronounced in the Neutral tone in the phrase bú shi, the original Falling tone of shi still causes bù to be pronounced with a Rising tone: bú.

6. A: NX xìng Fāng ma?

B: WS bú xìng Fāng.

7. A: WS xìng Wāng.

B: WS bú xìng Wang.

8. A: NX xìng MS ma?

B: Bú xìng MS. Xìng Wang.

Is your surname Fāng?

My surname isn't Fāng.

My surname is Wang.

My surname isn't Wang.

Is your surname Mǎ?

My surname isn't Mǎ. It's Wang.

|

WS |

shi |

Wang Dānián. | ||

|

(I |

am |

Wang Danián.) |

|

WS |

bú |

shi |

MS Xiānsheng. | |

|

(I |

am |

not |

Mr. Mǎ.) |

Note on No. 8

It is quite common in Chinese—much commoner than in English--to omit the subject of a sentence when it is clear from the context.

9. A: Nín guìxìng?

B: Wo xìng Wáng.

Your surname? (POLITE) My surname is Wáng.

Notea on No. 9

Nín is the polite equivalent of nī, "you."

Guìxìng is a polite noun, "surname." Guì means "honorable." Xìng, which you have learned as the verb "to be sumamed," is in this case a noun, "surname."

Literally, Nín guìxìng? is "Your surname?" The implied question is understood, and the "sentence" consists of the subject alone.

10. A: Nī jiào shénme?

B: Wǒ jiào Dànián.

What is your given name? My given name is Dànián.

Note on No. 10

Jiào is a verb meaning "to be called." In a discussion of personal names, we can say that it means "to be given-named."

11.

A:

B:

Nī hǎo a? Wǒ hǎo.

How are you? I’m fine.

Notes on No. 11

Notice that the Low tones of wo and nī change to Rising tones before the Low tone of hǎo: NÍ hǎo a? W§*hǎo.

Hǎo is a verb—"to be good," "to be well," "to be fine." Since it functions like the verb "to be" plus an adjective in English, we will call it an adjectival verb.

|

Wǒ |

hǎo. |

|

(I |

am fine.) |

|

Nī |

hǎo |

a? |

|

(You |

are fine |

?) |

12. A: Nī hào a?

How are you?

I’m fine. And you?

Fine, thanks.

B: W3 hSo. Nī ne?

A: H&o, xièxie.

Notes on No. 12

The marker ne makes a question out of the single word nī, ’’you": ’’And you?” or ”How about you?"

Xiè is the verb "to thank." "I thank you" would be W8 xièxie nī.

Xièxie is often repeated: Xièxie, xièxie.

13. míngzi given name

Note on No. 13

One way to ask what someone’s given name is: Nī jiào shénme míngzi?

A. Transformation Drill

1. Speaker: Tā shi Wang Xiānsheng* (He is Mr. Wang.)

2. Tā shi Hú Tàitai.

(She is Mrs. Hu.)

3. Tā shi Liú Tóngzhì.

(He is Comrade Liú.)

U. Tā shi Zhāng XiǎojiS.

(She is Miss Zhāng.)

J. Tā shi Mā Xiānsheng.

(He is Mr. Ma.)

6. Tā shi Fāng XiSojiS.

(She is Miss Fāng.)

7. Tā shi LÍn Tóngzhì.

(He is Comrade LÍn.)

You: Tā shi Wáng Xiānsheng ma? (Is he Mr. Wáng?)

Tā shi Hú Tàitai ma?

(Is she Mrs. Hú?)

Tā shi Liú Tóngzhì ma?

(Is he Comrade Liú?)

Tā shi Zhāng Xiǎojiě ma?

(Is she Miss Zhāng?)

Tā shi MS Xiānsheng ma?

(Is he Mr. Ma?)

Tā shi Fāng XiSojiě ma?

(Is she Miss Fāng?)

Tā shi LÍn Tóngzhì ma?

(Is he Comrade LÍn?)

B. Response Drill

1. Speaker: Tā shi Wang Xiānsheng ma? (Is he Mr. Wang?)

2. Tā shi Zhào Tàitai ma? (Is she Mrs. Zhào?)

3. Tā shi Chén Tóngzhì ma?

(Is she Comrade Chén?)

U. Tā shi Liú XiǎojiS ma? (Is she Miss Liú?)

5. Tā shi Song Xiānsheng ma?

(Is he Mr. Song?)

6. Tā shi Sūn Tàitai ma?

(Is she Mrs. Sūn?)

7. Tā shi Zhāng Xiānsheng ma?

(Is he Mr. Zhāng?)

You: Shi. Tā shi Wáng Xiānsheng (Yes. He is Mr. Wáng.)

Shi. Tā shi Zhào Tàitai. (Yes. She is Mrs. Zhào.)

Shi. Tā shi Chén Tóngzhì.

(Yes. She is Comrade Chén.)

Shi. Tā shi Liú Xiāojiā. (Yes. She is Miss Liú.)

Shi. Tā shi Sòng Xiānsheng.

(Yes. He is Mr. Song.)

Shi. Tā shi Sūn Tàitai.

(Yes. She is Mrs. Sun.)

Shi. Tā shi Zhāng Xiānsheng. (Yes. He is Mr. Zhāng.)

C. Response Drill

All of your answers will be negative. Give the correct name according to the cue.

|

1. |

Speaker: Tā shi Wang Xiānsheng ma? (cue) Liú (Is he Mr. Wang?) |

You: Bú shi. Tā shi Liú Xiānsheng. | |

|

(No. He is Mr. Liú,) | |||

|

2. |

Tā shi Gāo Xiǎojiě ma? (Is she Miss Gāo?) |

Zhao |

Bú shi. Tā shi Zhào Xiǎojiě. (No. She is Miss Zhào.) |

|

3. |

Tā shi Huáng Tóngzhì ma? (Is she Comrade Huáng?) |

Wáng |

Bú shi. Tā shi Wáng Tóngzhì. (No. She is Comrade Wang.) |

|

U. |

Tā shi Yáng Tàitai ma? (Is she Mrs. Yang?) |

Jiāng |

Bú shi. Tā shi Jiang Tàitai. (No. She is Mrs. Jiang.) |

|

5- |

Tā shi MS Xiānsheng ma? (Is he Mr. Ma?) |

Máo |

Bú shi, Tā shi Máo Xiānsheng. (No. He is Mr. >&o.) |

|

6. |

Tā shi Zhōu Xiǎojiě ma? (Is she Miss Zhōu?) |

Zhào |

Bú shi. Tā shi Zhào Xiǎojiě. (No. She is Miss Zhào.) |

|

7. |

Tā shi Jiāng Xiānsheng ma? Jiāng |

Bú shi. Tā shi JiSng Xiānsheng. (No. He is Mr. Jiāng.) | |

(Is he Mr. Jiāng?)

D. Response Drill

This drill is a combination of the two previous drills. Give an affirmative or a negative answer according to the cue.

(is she Mrs. Liú?) OR Tā shi Liú Tàitai ma? Huáng (Is she Mrs. Liú?)

U. Tā shi Táng Xiǎojiě ma? Táng (Is she Miss Tang?) |

You: Shì. Tā shi Liú Tàitai. (Yes. She is Mrs. Liú.) Bú shi. Tā shi Huáng Tàitai. (No. She is Mrs. Huáng.) Shì. Tā shi Wáng Xiāpsheng. (Yes. He is Mr. Wáng.) Bú shi. Tā shi Zhào Tàitai. (No. She is Mrs. Zhào.) Shì. Tā shi Táng Xiǎojiě. (Yes. She is Miss Táng.) |

|

5. Tā shi Huang Xiānsheng ma? Wang (Is he Mr. Huáng?) 6. Tā shi Zhang Tàitai ma? Jiāng (Is she Mrs. Zhāng?) E. Transformation Drill

(Are you Mr. Zhāng?)

(Are you Mrs. Zhào?)

(Are you Miss Jiāng?) U. Nī shi Liú Tóngzhì ma? (Are you Comrade Liú?)

(Are you Mrs. Song?)

(Are you Mr. Lī?)

F. Transformation Drill

(My surname is Zhāng.)

5. W3 xìng Sūn. |

Bú shi. Tā shi Wáng Xiānsheng. (No. He is Mr. Wáng.) Bú.shi. Tā shi Jiāng Tàitai. (No. She is Mrs. Jiāng.) You: Nī xìng Zhāng ma? (Is your surname Zhāng?) Nī xìng Zhào ma? (Is your surname Zhào?) Nī xìng Jiāng ma? (Is your surname Jiāng?) Nī xìng Liú ma? (Is your surname Liú?) Nī xìng Sdng ma? (Is your surname Sdng?) Nī xìng Lī ma? (Is your surname LI?) Nī xìng Sūn ma? (Is your surname Sūn?) You: W3 bú xìng Zhāng. (My surname is not Zhāng.) W3 bú xìng Chén. W3 bú xìng Huáng. W3 bú xìng Gāo. W6 bú xìng Sūn. |

|

6. W3 xìng Zhāng. 7. WS xìng Zhōu.

h. WS bú shi LÍn Tóngzhì.

(He is not Mr. Wáng.)

U. Tā bú shi Song XiāojiS. Sun 5. Tā bú shi Zhào Xiānsheng. Zhōu 6. Tā bú shi Jiāng Tóngzhì. Zhāng. 7« Tā bú shi Sūn Tàitai. Song |

Wǒ bú xìng Zhāng. WS bú xìng Zhōu. You: WS bú xìng Li. (My surname is not Li.) WS bú xìng Wang. WS bú xìng Chén. WS bú xìng LÍn. WS bú xìng Zhōu. Wo bú xìng Jiāng. WS bú xìng Sōng. You: Tā bú shi Wang Xiānsheng, tā xìng Huang. (He is not Mr. Wáng; his surname is Huáng.) Tā bú shi Jiāng Tàitai, tā xìng Jiāng. Tā bú shi Liú Tóngzhì, tā xìng LÍn. Tā bú shi Sōng Xiāojiā, tā xìng Sūn. Tā bú shi Zhào Xiānsheng, tā xìng Zhōu. Tā bú shi Jiāng Tóngzhì, tā xìng Zhāng. Tā bú shi Sūn Tàitai, tā xìng Sōng. |

|

I. |

Expansion Drill | |||

|

1. |

Speaker: W3 bú xìng Fang. (cue) Hú (My surname is not Fang.) |

You: Wō bú xìng Fāng, xìng Hú. (My surname is not Fāng; it’s Éú.) | ||

|

2. |

W8 bú xìng Sun. |

Song |

Wō |

bú xìng Sun, xìng Sōng. |

|

3- |

Wō "bú xìng Yang. |

Tang |

Wō |

bú xìng Yáng, xìng Táng. |

|

U. |

W8 bú xìng Jiāng. |

Zhāng |

Wō |

bú xìng Jiāng, xìng Zhāng. |

|

5. |

W8 bú xìng Zhōu. |

Zhāo |

Wō |

bú xìng Zhōu, xìng Zhāo. |

|

6. |

W8 bú xìng Wáng. |

Huang |

Wō |

bú xìng Wang, xìng Huáng. |

|

7. |

W8 bú xìng Jiāng. |

Jiāng |

wō |

bú xìng Jiāng, xìng Jiāng. |

J. Response Drill

|

1. |

Speaker: Tā shi Wang Xiānsheng ma? (cue) Wáng |

You: Shì. Tā shi Wáng Xiānsheng. (Yes. He is Mr. Wáng.) Tā bú shi Wáng Xiānsheng. Tā xìng Huáng. (He is not Mr. Wang. His surname is Huáng.) | |||

|

OR |

(is he Mr. Wáng?) Tā shi Wang Xiānsheng ma? Huáng (Is he Mr. Wang?) | ||||

|

2. |

Tā |

shi |

Liú Tàitai ma? Lin |

Tā bú shi Liú Tàitai. Tā xìng Lin. | |

|

3. |

Tā |

shi |

Chen Xiāojiā ma? |

Chen |

Shì. Tā shi Chen Xiāojiā. |

|

1*. |

Tā |

shi |

Mao Xiānsheng ma? |

Máo |

Shì. Tā shi Máo Xiānsheng. |

|

5- |

Tā |

shi |

Jiāng Tóngzhì ma? |

Zhāng |

Tā bú shi Jiāng Tóngzhì. Tā xìng Zhāng. |

|

6. |

Tā |

shi |

Sōng Tàitai ma? |

Sōng |

Shì. Tā shi Sdng Tàitai. |

|

7. |

Tā |

shi |

Li Xiānsheng ma? |

Wáng |

Tā bú shi Lī Xiānsheng. Tā xìng Wáng. |

K. Transformation Drill

(My surname is Wang.)

U. W3 xìng Huáng.

L. Transformation Drill

(My surname is Wáng, and my given name is Dànián.)

U. W3 xìng Fang Jiao Baolán.

|

Student 1: Tā xìng shénme? (What is his surname?) Student 2; Tā xìng Wáng. (His surname is Wang.) SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Chén. SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Liú. SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Huáng. SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Song. SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Lī. SI: Tā xìng shénme? S2: Tā xìng Wáng. You: Nī xìng Wang jiào shénme? (Your surname is Wáng, and what is your given name?) Speaker: Dànián. (Dànián.) Nī xìng Hú jiào shénme? Milling. Nī xìng Lī jiào shénme? Shìyīng. Nī xìng Fāng Jiào shénme? Baolán. Nī xìng Sun jiào shénme? Déxián. Nī xìng Chén jiào shénme? Huìrán. Nī xìng Zhang jiào shénme? Zhènhàn. |

|

M. |

Combination Drill | |||

|

1. |

Speaker: Tā xìng Chén. Tā Jiào Bāolán. (Her surname is Chén*. Her given name is Baolan.) |

You; Tā xìng Chén, Jiào Bāolán. (Her surname is Chén, given name Bāolán.) | ||

|

2. |

Tā |

xìng LI. Tā Jiào Mínglī. |

Tā |

xìng LX, Jiào Mínglí. |

|

3. |

Tā |

xìng Hú. Tā jiao Bāolān. |

Tā |

xìng Hú, Jiào Bāolán. |

|

k. |

Tā |

xìng Jiāng, Tā Jiào Dexián. |

Tā |

xìng Jiāng, jiào Déxián. |

|

5. |

Tā |

xìng Zhōu. Tā jiào Zīyàn. |

Tā |

xìng Zhōu, Jiào Zīyàn. |

|

6. |

r.'ā |

xìng Zhāng. Tā jiào Tíngfēng. |

Tā |

xìng Zhāng, Jiào Tíngfēng. |

|

7. |

Tā |

xìng Chén. Tā jiào Huìrán. |

Tā |

xìng Chén, Jiào Huìrán. |

Topics Covered in This Unit

1. Nationality.

2. Home state, province, and city.

Prerequisites to the Unit

1. PSR 5 and P&R 6 (Tapes 5 and 6 of the resource module on Pronunciation and Romanization).

2. NUM 1 and NUM 2 (Tapes 1 and 2 of the resource module on Numbers), the numbers from 1 to 10.

Materials You Will Need

1. The C-l and P-1 tapes, the Reference List and Reference Notes.

2. The C-2 and P-2 tapes, the Workbook.

3. The 3D-1 tape.

|

1. |

A: B: |

Nl shi MSiguo rén ma? Wō shi MSiguo rén. |

|

2. |

A: B: |

Nī shi Zhōngguo rén ma? Wō shi Zhōngguo rén. |

|

3. |

A: |

Wang Xiānsheng, nī shi |

Yingguo rén ma?

B: Wō bú shi Yingguo rén.

1». A: Nī shi Zhōngguo rén ma?

B. Bú shi.

A: Nī shi MSiguo rén ma?

B: Shì.

5. A: Mā Xiāojiā shi MSiguo rén ma?

B: Bú shi, tā bú shi MSiguo rén.

A: Tā shi Zhōngguo rén ma?

B: Shì, tā shi Zhōngguo rén.

6. A: mt shi nSiguo rén?

B: W3 shi MSiguo rén.

7. A: Tā shi nSiguo rén?

B: Tā shi Yingguo rén.