Emerson's Optimism

George Miller

The following is a paper written and given by George Miller:

Since this is the last of the Reading Revolutions series, I think that it would be fitting to begin with a quote from Emerson on old books.

(Spiritual Laws, 145-6): "The effect of any writing on the public mind is mathematically measurable by its depth of thought. How much water does it draw? If it awaken you to think, if it lift you from your feet with the great voice of eloquence, then the effect is to be wide, slow, permanent, over the minds of men".

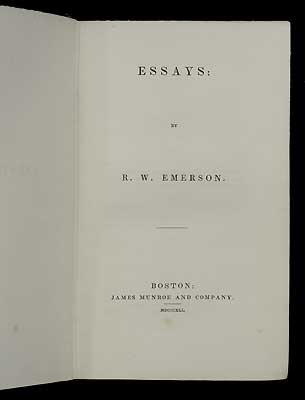

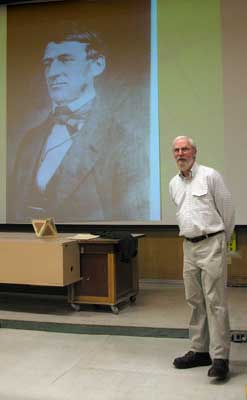

This is Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was born in 1803. He was a leader of the transcendentalist movement, lived in Boston and Concord for most of his life, and made his living first, as a Unitarian minister, and later as a lecturer. I could tell you a lot of other historical facts about him, but I'm not going to do it. I think that Emerson would have disliked being introduced as a figure of historical importance. The truth which interested Emerson was the truth of the present, the truth as it is experienced by each of us, right now. His first published book began with these words:

This is Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was born in 1803. He was a leader of the transcendentalist movement, lived in Boston and Concord for most of his life, and made his living first, as a Unitarian minister, and later as a lecturer. I could tell you a lot of other historical facts about him, but I'm not going to do it. I think that Emerson would have disliked being introduced as a figure of historical importance. The truth which interested Emerson was the truth of the present, the truth as it is experienced by each of us, right now. His first published book began with these words:

"Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we also have a poetry and philosophy of insight and tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?" (Nature)

His books, if they are to be true to this spirit, must speak to us directly, as though Emerson himself were standing here, talking to us about our lives, and the way we live. So I'm going to start off by talking about us, and our condition, and then I'll introduce Emerson as someone who has something to say to us, about our condition.

In academic life, there is a constant tension between a commitment to our best beliefs, and a skeptical, or at least critical attitude toward those same beliefs. On the one hand, we believe that some ideas are better than others, and that we can tell the difference. We believe that Newton's theory is better than Aristotle's, and that Einstein's theory is better than Newton's, and we think that we can explain why. On the other hand, we are always trying to improve our beliefs, and in that process we subject our best beliefs to constant doubt and scrutiny. This tension is productive, as long as we are confident in our ability to tell which ideas are better than others, but for the last 100 years or so there has been a growing doubt about our ability to do this, as individuals, in some sections of the academic world. This is what postmodernism is all about. It's essentially a self-doubt, a doubt about my own ability, and by extension the ability of anyone else, to tell for sure which idea is better than another.

There are some good reasons for having this doubt. For one thing, we have become more aware, and more respectful of other cultures, and other cultures sometimes seem to reach different conclusions from us, about which ideas are better. In addition, we have witnessed the holocaust, and 9-11, and a lot of other tragedies perpetrated by people who believed that they knew the truth, and were doing the right thing. The suicide bombers in Israel, Timothy McVeigh, and a host of other examples all seem to tell us that a strong dose of self-doubt is a good thing for people to have.

But speaking against all this, we have Emerson. On the first page of his essay on Self-Reliance, he says:

"To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men, --that is genius. Speak your latent conviction, and it shall be the universal sense; for the inmost in due time becomes the outmost, and our first thought is rendered back to us by the trumpets of the Last Judgment." (Self reliance 47).

Emerson was an optimist about a lot of things-- about the goodness of human nature, and the goodness of the universe as a whole, among other things. But he was also an optimist about our ability to know the truth. Emerson's basic message is that if we will just be self-reliant, if we will trust our deepest instincts and most basic beliefs, we cannot go wrong.

He's not saying that we should be dogmatic, and hold onto our ideas no matter what. Emerson believed that we should be reflective, open to new ideas, and willing to learn. What he's insisting is that when we think we have encountered the truth, we should trust that feeling.

Self-reliance is basically trusting yourself, thinking and acting on your own most fundamental beliefs and intuitions. (47-48) Emerson insists that we should not value books (not even the bible) nor other people more than ourselves as sources of truth. Imitation, he says, is suicide. (48)

Self-reliance is basically trusting yourself, thinking and acting on your own most fundamental beliefs and intuitions. (47-48) Emerson insists that we should not value books (not even the bible) nor other people more than ourselves as sources of truth. Imitation, he says, is suicide. (48)

I may choose to agree with you, and do as you do, but it must be because I think it is right, and not because you think it is right.

The most important thing in life is not to be swayed in your own mind by the opinions of others:

"He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind." (Self-reliance 52)

So: why is self-reliance so important, for Emerson-- the foundation of his ethics, and the only way to live well? The key to understanding this, is to see that your own character, and your own choices are your only access to goodness, truth, and existence itself. YOU are not really doing anything, unless you are doing it on the basis of your own values and judgment. That is why imitation is suicide.

In Emerson's words, "The objection to conforming to usages that have become dead to you is that it scatters your force. It loses your time and blurs the impression of your character". (55)

In essence, he is saying that YOU can only have an effect on the world by acting on your own motives and beliefs. Emerson gives examples of maintaining a "dead church", or "voting with a great party". As soon as you act as a function of some institution or some other person rather than on the basis of your own belief, you are diminished.

Only by acting on your own beliefs can you develop, and discover what you can do in life, what you are uniquely fitted for. (48) According to Emerson, everyone has a calling, but you'll never find it without self-reliance. (See also Spiritual Laws, 134)

Furthermore, he says there is no truth in your words and thoughts unless your speak and think your own convictions, based on what is evident to you, in your own mind. When you acquire your opinions from others, there has been no real discovery of truth, according to Emerson. He says:

"Most men have bound their eyes with one or another handkerchief, and attached themselves to some one of these communities of opinion. This conformity of opinion makes them not false in a few particulars, authors of a few lies, but false in all particulars. Their every truth is not quite true. Their two is not the real two, their four not the real four.." (56)

Emerson is saying here, that memorizing the words "two plus two equals four" is not enough to be able to speak the truth, that two plus two equals four. I have to know what it means, and I have to be able to see for myself that two plus two equals four. The same point holds for goodness, beauty, and everything else of value in life, according to Emerson. Our only access to truth, goodness, or to life itself, is through our own understanding and

our own judgments. To the extent that we live by other people's

understanding and judgments, we not only lose all hope of experiencing value

in our lives, but there is a sense in which we literally cease to exist.

Emerson is saying here, that memorizing the words "two plus two equals four" is not enough to be able to speak the truth, that two plus two equals four. I have to know what it means, and I have to be able to see for myself that two plus two equals four. The same point holds for goodness, beauty, and everything else of value in life, according to Emerson. Our only access to truth, goodness, or to life itself, is through our own understanding and

our own judgments. To the extent that we live by other people's

understanding and judgments, we not only lose all hope of experiencing value

in our lives, but there is a sense in which we literally cease to exist.

So Emerson is saying that to live fully, we need to act on our own beliefs. This is a powerful point, but it doesn't directly address the worry I raised earlier-- the worry that we are fallible, and might not really know how to tell which idea is better than another. Fanatics like Hitler, and the suicidal terrorists of 9/11, have taught us to be wary of absolute convictions. So why should we trust our own deepest convictions? Isn't it safer to rely on other people, and regard the pursuit of truth and goodness as a group enterprise? Or to reject the pursuit of truth entirely, as some postmodern advocate?

Emerson has an answer to this worry about the fallibility of individual judgment. He says that the self we should rely on, in self-reliance, is not the superficial self with its everyday desires, fears, and prejudices. The self he has in mind lies deeper in our character, and it is ultimately the mental side of the universe itself, something like the atman of the Buddhists. (64-65) Our most deeply held views are trustworthy, according to Emerson, because they stem from the universal nature which underlies all things, in which we are at one with all things and other people.

He says: "We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity". The perception which arises from this being is involuntary, and a perfect faith is due to it.

This is the core of Emerson's optimism: he believes that we are ultimately good because we are each, as individuals, just particular aspects or expressions of a single underlying being, which is the only source of good in the universe. Sometimes, Emerson calls this being God; at other times he calls it "the oversoul", or the "universal mind". Basically, he was a kind of pantheist. According to Emerson God is in everything, and everything is God. All we have to do to choose rightly, is to choose according to the most basic impulses of our own being. Such a choice is actually not a choice, as the term is usually understood; it is almost passive. It is going with the flow, or being "in the groove".

Emerson puts it this way: "I say, do not choose; but that is a figure of speech by which I would distinguish what is commonly called choice among men, and which is a partial act, the choice of the hands, of the eyes, of the appetites, and not a whole act of the man. But that which I call right or goodness, is the choice of my constitution; and that which I call heaven, and inwardly aspire after, is the state or circumstance desirable to my constitution; and the action which I in all my years tend to do, is the work for my faculties." (Spiritual laws, 133)

This kind of choice of the whole being, which is in conformity with the universe as a whole, is very similar to Taoism. (Read excerpt from Chuang Tzu, "Nurturing Life" as an example.)

When you live like this, you are in Emerson's view most fully yourself, and the result is inner peace. "A man is relieved and gay when he has put his heart into his work and done his best; but what he has said and done otherwise shall give him no peace." (49)

So all right, we might say, we skeptical post moderns of the twenty-first century. We would ask Emerson this: suppose we do learn how to act from our deepest impulses, and we have inner peace. Couldn't we still be mistaken about the source of this self-evidence, and the goodness of our actions? Couldn't Hitler have acted from his own deepest impulses? Emerson considered this objection, and he replied that the only moral truth that matters is conformity to your own deepest nature.

"..my friend suggested, --'But these impulses may be from below, not from above.' I replied, 'They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil's child, I will live then from the Devil." (52)

Of course, Emerson did not believe that his deepest impulses came from the devil; he believed that the unity underlying all things, and its goodness, were universal, and as evident and clear as anything that can be perceived.

He says that "all persons have their moments of reason, when they look out into the region of absolute truth...", (73) (See also 255)

The reason Emerson was so convinced of this, was that he had something more to go on than a few moments of reason, a few fleeting glimpses of the region of absolute truth. He had experienced total emersion in the region of absolute truth. Emerson was a mystic.

Mystics have unusual experiences of a certain kind, of a unity underlying all things. In this type of experience things seem to be not just interconnected, but unified, they are at bottom one thing, including the self doing the experiencing. This type of experience is reported in just about all cultures and all times. In its full-blown and complete state, this type of experience is rare, especially in Western cultures. In Tibet, and some other cultures, mystics are more commonplace. But even in the West, experiences are common which involve some loss of the sense of self, and a sense of being "at one" with other things, or other people, to a lesser degree.

- nature: looking at a sunset, or the ocean, or a mountain

- listening to music

- (sometimes, sex

- being with someone you know well, and care about deeply

- team play-- a sense of being part of the team more than being yourself, or in the cast of a play

- really intense, good conversation

Emerson quote, oversoul 260: "In all conversation between two persons tacit reference is made, as to a third party, to a common nature. That third party or common nature is not social; it is impersonal; is God. And so in groups where debate is earnest, and especially on high questions, the company become aware that the thought rises to an equal level in all bosoms, that all have a spiritual property in what was said, as well as the sayer. They all become wiser than they were. It arches over them like a temple, this unity of thought in which every heart beats with nobler sense of power and duty, and thinks and acts with unusual solemnity. All are conscious of attaining to a higher self-possession."

Imagine such an experience to be total, to involve a total loss of the sense of individual self, and have instead a sense of unity with all other things. That would be the full-blown mystical experience.

Imagine such an experience to be total, to involve a total loss of the sense of individual self, and have instead a sense of unity with all other things. That would be the full-blown mystical experience.

Such experiences change those who have them; the experience seems to be an experience of a greater reality, or a higher level of reality than the one we experience perceptually. They have a strong weight of evidence. Just as the perceptual world seems more real than the world of dreams, the world of mystical experience seems like an "awakening" to those who have it, to a world of a greater reality than the perceptual one.

What's it like? It's not like anything else, so it can't be described exactly for anyone who hasn't had it. It's ineffable. Similarly, you can't explain colors to someone who's been blind from birth. But the mystics have tried. I'll read some descriptions. First, Emerson.

(Self-reliance 68-69): "And now at last the highest truth on this subject remains unsaid, probably cannot be said; for all that we say is the far-off remembering of the intuition. That thought by what I can now nearest approach to say it, is this. When good is near you, when you have life in yourself, it is not by any known or accustomed way; you shall not discern the footprints of any other; you shall not see the face of man; you shall not hear any name; --the way, the thought, the good, shall be wholly strange and new. It shall exclude example and experience...In the hour of vision there is nothing that can be called gratitude, nor properly joy. The soul raised over passion beholds identity and eternal causation, perceives the self-existence of Truth and Right, and calms itself with knowing that all things go well. Vast spaces of nature, the Atlantic Ocean, the South Sea; long intervals of time, years, centuries, are of no account. This which I think and feel underlay every former state of life and circumstances, and what is called life and what is called death."

(Oversoul, 252-253): The oversoul is that "within which every man's particular being is contained and made one with all other; that common heart of which all sincere conversation is the worship, to which all right action is submission... We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one."

Compare Emerson's account with some excerpts from various religious traditions: (from Mysticism by F C Happold)

From Upanishads:

The Self is one. Unmoving, it moves faster than the mind. The senses lag, but Self runs ahead. Unmoving, it outruns pursuit. Out of Self comes the breath that is the life of all things.

Unmoving, it moves; is far away, yet near; within all, outside all. The Self is everywhere, without a body, without a shape, whole, pure, wise, all knowing, far shining, self-depending, all transcending; in the eternal procession assigning to every period its proper duty.

From Lao Tzu:

The Tao which can be expressed in words is not the eternal Tao; the name which can be uttered is not the eternal name. Without a name it is the Beginning of Heaven and Earth; with a name, it is the mother of all things. Only one who is ever free of desire can apprehend its spiritual essence; he who is a slave to desire can see no more than its outer fringe. These two things, the spiritual and the material, though we call them by different names, in their origin are one and the same. This sameness is a mystery-- the mystery of all mysteries.

If the mystical vision is the highest truth, and the source of Emerson's confidence in the self, one would like to know, how the mystical vision can be achieved. Emerson is less helpful on this topic than other mystics. The basic answer, in a lot of mystical traditions, seems to be that to experience the mystical vision, you have to make the usual inner clamor of your thoughts and desires completely quiet. One way to do this is to learn to focus your attention completely on a single thing, for a long time. Sometimes this is called meditation.

Emerson himself seems to have found that the best way to achieve mystical enlightenment, was to take a walk in the woods. He says:

"In the woods we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befal me in life, --no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, -- my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, --all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball. I am nothing. I see all. The currents of Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God." (Nature, p 10, in Collected Works vol 1, Ferguson, ed.)

Emerson was aware, however, that most people do not experience the woods as he did. When a woodcutter goes into the woods, says Emerson, he just sees sticks of timber. (Nature p 9) And in fact, he says, "few adult persons can see nature." But he seems less concerned with experiencing the unity of all things than with living in harmony with that unity. It is not through mystical vision, but through self-reliance, that such harmony is achieved. Mystical vision shows us the whole truth, but it seems that for Emerson, it is more important to live in harmony with the truth than to see it. And we can live in harmony with the truth, even if we don't see it completely, by simply being ourselves, and trusting our deepest impulses. We may not experience the whole truth of mystical vision, but we will see those aspects of the truth that are appropriate for us as individuals. He says:

"A man is a method, a progressive arrangement; a selecting principle, gathering his like to him wherever he goes. He takes only his own out of the multiplicity that sweeps and circles round him. He is like one of those booms which are set out on rivers to catch drift-wood, or like the loadstone amongst splinters of steel." (Spiritual Laws, 137)

Evil comes into the world, for Emerson, because people are capable of being superficial, and ignoring their deepest impulses and beliefs. He did not see evil as a positive force, but rather as a failure to be fully what a person should be-- that is, a particular expression of the unity underlying all things. Because everything is at bottom one, an evil action is automatically and unfailingly a loss of Being for the one who does it. A good action is an enhancement of Being in the life of the one who does it.

"In a virtuous action, I properly AM; in a virtuous act I add to the world; I plant into deserts conquered from Chaos and Nothing and see the darkness receding on the limits of the horizon." (117)

In good actions we do the work of the oversoul, and our true nature (as an instantiation of the oversoul) is allowed to express itself. In evil actions, we not only fail to make use of an opportunity for good; we also ignore our true nature, and in trying to be something we are not (something completely separate from the whole-- an independent person) we fail to exist as fully as we could.

Emerson says, suppose a criminal "adheres to his vice and contumacy, and does not come to a crisis or judgment anywhere in visible nature... Has he therefore outwitted the law? Inasmuch as he carries the malignity and the lie with him he so far decreases from nature." (117)

There is thus an automatic retribution for evil: because what we are is basically the oversoul, and the oversoul is essentially good, every evil act is a reduction of the actual existence of the perpetrator. Evil is not a positive thing, for Emerson; it is rather a loss of goodness, it is essentially negative. There is no devil, there is only less Being in some people than in others. So he says (in an example) that a brave man is more of a man than a coward; the true, benevolent and wise are more 'man' than the knaves and cowards. (117-118)

This view of evil, by the way, gets some support in the twentieth century from Hannah Arendt, who interviewed Eichmann in Jerusalem during the Nuremberg trials. She concluded that he was able to govern the death camps only because he had become completely shallow and unreflective. He was something less than a normal human being.

This loss of Being which accompanies evil is, for Emerson, just one aspect of the system of natural justice in the world, which he calls "compensation". I won't go into the other aspects because it's a complicated story. The evidence of the loss of Being which accompanies evil is just one of the ways that the oversoul is evident, for Emerson, but it underscores his main contention: that self-reliance is the best way to live because it is the only way to fully exist. Being, and Being good are ultimately the same thing for Emerson, because we truly exist only as instantiations of the oversoul.

So Emerson believes that we should trust our most basic impulses, because only in that way can we fully exist, and he believes that our basic instincts are trustworthy because we are all at bottom just aspects of one universal being, which he sometimes calls the oversoul. The most difficult part of this argument for many to accept, is the claim that there is an oversoul.

Is there an oversoul? Many mystics have said so, in many cultures, and in many times. Of course they could be wrong. What appears to be the oversoul could be the individual consciousness, which underlies our experience of everything. How do I see you, or this lectern, or the door? A part of my mind is being used to represent these things. Perhaps in mystical experience, I just cease to distinguish between the part of my mind which functions as myself, as the conscious ego, and the part which is being used to represent the rest of the world, in all the perceptual images of things. So maybe there is no oversoul, and maybe it would be a mistake to trust our deepest impulses and beliefs.

But the strong claims of the mystics should give pause to all of those who are non-mystics. The mystics claim that if you have the experience, then you know it is of a higher reality, just as we know that perceptual experience is of a higher reality than the world of dreams. What if they are right? If Emerson is right, then being good and just "Being" are at bottom the same thing. I can only fully exist by living in harmony with the oversoul. To the extent that I reject my connection with the oversoul, I will fail to experience life as fully as I might.

I'm reminded of a story, a film I recently saw with my daughter. There is a film, called "Polar Express", about a boy who is in doubt about Santa Claus. He doesn't exactly believe, and he doesn't exactly disbelieve, either. He's on the fence, he can't make up his mind. A train comes in the middle of the night, and takes him off to the North Pole, where he sees elves, and Santa, but all this time he's not sure whether he's having a dream. Then

a bell falls off the harness on Santa's sleigh, and he picks it up in his hand and shakes it, but he can't hear the sound of the bell. He wants more than anything to hear the sound of that bell. All the other children around him can hear it, but he can't. At that point, he gets off the fence; he makes up his mind. He chooses to believe, and the moment he chooses to believe, he can hear the bell. At the end of the film, he still has the bell, and for the rest of his life he is able to hear it, even when it makes no sound for all the people around him.

I'm reminded of a story, a film I recently saw with my daughter. There is a film, called "Polar Express", about a boy who is in doubt about Santa Claus. He doesn't exactly believe, and he doesn't exactly disbelieve, either. He's on the fence, he can't make up his mind. A train comes in the middle of the night, and takes him off to the North Pole, where he sees elves, and Santa, but all this time he's not sure whether he's having a dream. Then

a bell falls off the harness on Santa's sleigh, and he picks it up in his hand and shakes it, but he can't hear the sound of the bell. He wants more than anything to hear the sound of that bell. All the other children around him can hear it, but he can't. At that point, he gets off the fence; he makes up his mind. He chooses to believe, and the moment he chooses to believe, he can hear the bell. At the end of the film, he still has the bell, and for the rest of his life he is able to hear it, even when it makes no sound for all the people around him.

In some ways, I think that little parable explains Emerson better than anything. He certainly saw things differently from most other people in his own time, and he is perhaps even farther from the norm of the twenty first century. So it's not easy to see the world as he saw it. When you first pick up one of his books and start reading, it's just as though some little boy came up to you and said "look at this great little bell. It fell off of Santa's sleigh. Doesn't it sound great?" And the little boy shakes the bell, but you can't hear a thing. But if you keep reading, you'll be impressed by Emerson's passion, the depth of his thought, and his sincerity, and little by little you'll begin to hear the sound of his bell.

George Miller

Quotations in text, unless otherwise stated, from:

Emerson,

Ralph Waldo. "Essays First Series". in Riverside Edition, Vol. II,

of Emerson's Complete Works. Boston: Houghton Mifflen and Co.,

1883.

Quotation from "Nature" from:

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature, Addresses, and Lectures" in Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Vol. 1. (ed. ). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971, pp. 7-45.

Following the presentation the audience was invited to examine the essays.

|