In Defense of Bad Books: Milton's Areopagitica

Eric Brown

The following is based on the lecture given by Eric Brown.

Francis Bacon, a contemporary of Milton's, said in his essay on studies: "Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested: that is, some books are to be read only in parts, others to be read, but not curiously, and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention." Milton might add to that -- some books are to be eaten and then thrown out. That is to say that they should be read and thought about and only after that can they be dealt with. They can't be thrown out or suppressed before they are read. In Areopagitica it is pre-publication censorship that is at issue rather than the censoring of books after they have been published. We will see that Milton isn't totally against censorship, but is writing in response to a law that would stop books from being printed at all, before they can be read.

|

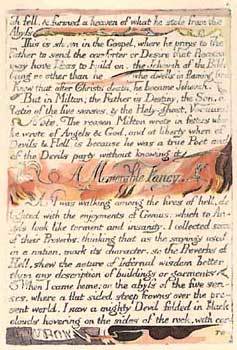

Milton has a complex image in

literary history. William Blake said in his The Marriage of

Heaven and Hell (1790) "The reason Milton wrote in fetters

when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell,

is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without

knowing it." Inspired by this quote, in the 1997 film

The Devil's Advocate the Satan character is called John Milton.

There are so many sides to Milton that even Blake was in awe.

Milton (1608 - 1674) was educated in Cambridge. He returned home for a period but then traveled to France and Italy in the late 1630's and met and talked with people including Galileo. This was part of his education, the experience was something that he valued all his life. In 1642 he married. He was 34 and she was 17. The age difference was not uncommon and would have been fine, but she liked the high life, wanted to go out and to entertain. Milton wasn't good at that sort of thing so the marriage initially lasted about three months. She left Milton and returned to her family. Milton soon after published one of his famous treatises "The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce." He argued that divorce should be allowed not only for infidelity but also on other grounds such as incompatibility which he had experienced first hand! This was a radical idea at the time and Milton was excoriated for it. Being labeled a "gay divorcer" haunted Milton his entire life, in spite of the fact that he was married three times, and did not actually ever divorce. His first wife returned to him in 1645 and bore four children, three girls and a boy. She died in 1652 days after a daughter, Deborah, was born. He married again in 1656 but both his wife and the daughter of that marriage died in 1658. Finally, in 1663 he married a third time (against the wishes of his family). All three marriages seem to have been happy. The controversy surrounding the divorce treatise was so strong that his reputation as a divorc é persisted in spite of a long domestic life. Further controversy surrounded him because the treatise was never licensed. That is, permission was never granted to publish. He did it anyway. He got a publisher to publish it. His radical views gave him a vested interest in the way in which books were published. The means, the methods, the mechanics of publishing in his day serve as a backdrop to the Areopagitica, 1644. |

|

We think of John Milton as a poet today,

the author of Paradise Lost. In 1645 his first book of

poetry, simply called Poems, was registered and published. This

was a major publication, but until Paradise Lost was published in

1667 he was more engaged with polemics with regard to political and

religious issues of the day. He wrote a whole series of pamphlets.

Three of the most controversial were; against bishops in 1642, his treatise on divorce in 1644,

and in 1649

shortly after the execution of Charles I his Tenure of Kings and

Magistrates was published supporting regicides. This was the time of the

Civil War in England and Milton was on the side of the republicans.

The beheading of Charles I was a shocking event at the time, aside from the

fact that he was head of government, the tradition of the Divine

Right of Kings and power derived from God placed a religious value on the

life of a king. Milton proposed more

earthly standards for judging the fitness of rulers and argued the right of

the people to rid themselves of tyrants.

We think of John Milton as a poet today,

the author of Paradise Lost. In 1645 his first book of

poetry, simply called Poems, was registered and published. This

was a major publication, but until Paradise Lost was published in

1667 he was more engaged with polemics with regard to political and

religious issues of the day. He wrote a whole series of pamphlets.

Three of the most controversial were; against bishops in 1642, his treatise on divorce in 1644,

and in 1649

shortly after the execution of Charles I his Tenure of Kings and

Magistrates was published supporting regicides. This was the time of the

Civil War in England and Milton was on the side of the republicans.

The beheading of Charles I was a shocking event at the time, aside from the

fact that he was head of government, the tradition of the Divine

Right of Kings and power derived from God placed a religious value on the

life of a king. Milton proposed more

earthly standards for judging the fitness of rulers and argued the right of

the people to rid themselves of tyrants.

In 1651 Milton was probably completely blind and by 1652, certainly was. It was in that year that his first wife, Mary, died. This began a difficult period for Milton. But he continued his political work and writing, holding important positions within the Republic. In 1658 Cromwell died and the Republic began to fall apart. The royalists become more powerful all through 1659. The Restoration was not well timed for Milton, he had just come out with A Treatise of Civil Power and Ready and Easy Way To Establish a Free Commonwealth in 1659. Late that year he was arrested and imprisoned both for his work in the support of the Republic and his writings. He was released after paying an enormous fine after friends petitioned Parliament. Charles II returned to the throne in 1660. Milton retired from public life and devoted himself to poetry. He died in 1674.

Knowledge

of the issues and conditions during the Civil War and the Republic are

necessary to understand

Areopagitica but we must also look at the field of publishing and books.

The first copyright act was not passed until 1710 in England. In the

early 1600's writers would enter their work into the Stationer's

Register. This was managed by a guild of publishers and printers who

agreed that if

a work showed up on this list they agreed not to publish pirated copies

of it. The agreement offered some protection to both authors and

publishers but it did not have the power of copyright. There were

no restrictions on what could be published. This did not suffice for

Charles I. With growing unrest in the country he moved to suppress

opposition.

Knowledge

of the issues and conditions during the Civil War and the Republic are

necessary to understand

Areopagitica but we must also look at the field of publishing and books.

The first copyright act was not passed until 1710 in England. In the

early 1600's writers would enter their work into the Stationer's

Register. This was managed by a guild of publishers and printers who

agreed that if

a work showed up on this list they agreed not to publish pirated copies

of it. The agreement offered some protection to both authors and

publishers but it did not have the power of copyright. There were

no restrictions on what could be published. This did not suffice for

Charles I. With growing unrest in the country he moved to suppress

opposition.

Charles I (1625 - 1649) was not a popular king. He was wildly extravagant, authoritarian, and rigid. When he was challenged by Parliament, he dismissed it and refused to call for Parliament for eleven years from 1629 to 1640. Following his own beliefs, he tried to impose a State religion on the people that would include more aspects of the pomp and ceremony of the Catholics. Many of the members of Church of England and members of other Protestant groups preferred a plainer liturgy. The division became known as "high" vs. "low" church. Charles established a "Star Chamber" of ministers to enforce his commands. They ignored the need for lawful process and acted as enforcers. All proceedings of the Star Chamber were conducted behind closed doors.

An example of what could happen to an individual who disobeyed the censorship of Charles I is the case of William Prynne. In 1632 Prynne, a Puritan, published Histriomastix in which he condemned just about everything fun, including dancing, music and masques. Women who participated in masques were slatterns. The Queen was fond of masques, a type of fancy-dress ball and took offense at this characterization. The King was a patron of the arts. Various bishops within the Anglican Church pushed to have this outspoken and powerful Puritan arrested. Prynne was called before the Star Chamber and convicted of sedition. He had the tips of his ears cut off, paid an enormous fine, lost his degrees, and his possessions were sold. He continued to write from prison with the result that in 1637 the remainder of his ears were cut off, he was branded on both cheeks with the letters "SL" for seditious libel, and he was sent to an awful prison rather than the Tower. What is more, the Puritan printers who had published his works were also tried and convicted. It was not just the author, but the press which was found guilty. It is one thing to write about something you believe deeply and defend it, it is another to face death for printing someone else's passions.

Without Parliament, Charles I had no legal way of imposing taxes so he raised money through fines and fees. This was less popular than anything else he did. Protests and resistance became stronger. In 1640 he called Parliament into session to attempt to regain control of the country. One of the first things that Parliament did in 1640 was to free Prynne. By 1642 the country was immersed in a Civil War. Parliament wished to suppress opposition just as much as the Charles had. Where Charles I had worked to censor speech and print through the Star Chamber, Parliament formalized it for their own purpose in 1643. Ostensibly the law would simply strengthen the Stationer's Register, but in effect, it transferred power from the stationers to Parliament, to the government.

Ordinance for correcting and regulating the Abuses of the Press.

"Whereas divers good Orders have been lately made, by both Houses of Parliament, for suppressing the great late Abuses, and frequent Disorders, in printing many false, forged, scandalous, seditious, libellous, and unlicensed Papers, Pamphlets, and Books, to the great Defamation of Religion and Government; which Orders (notwithstanding the Diligence of the Company of Stationers to put them in full Execution) have taken little or no Effect, by reason of the Bill in Preparation for Redress of the said Disorders having hitherto been retarded through the present Distractions; and very many, as well Stationers and Printers, as others of sundry other Professions,

not free of the Stationers Company, have taken upon them to set up sundry private Printing Presses in Corners, and to print, vend, publish, and disperse, Books, Pamphlets, and Papers, in such Multitudes, that no Industry could be sufficient to discover, or bring to Punishment, all the several abounding Delinquents; and, by reason that divers of the Stationers Company, and others, being Delinquents (contrary to former Orders, and the constant Custom used among the said Company), have taken Liberty to print, vend, and publish, the most profitable vendible Copies of Books belonging to the said Company, and other Stationers, especially of such Agents as are employed in putting the said Orders in Execution, and that by Way of Revenge for giving Information against them to the Houses, for their Delinquency in Printing, to the great Prejudice of the said Company, Stationers, and Agents, and to their Discouragement in this Public Service: It is therefore Ordered, by the Lords and Commons in Parliament, That no Order or Declaration of both or either House of Parliament shall be printed by any, but by Order of One or both the said Houses; nor other Book, Pamphlet, or Paper, shall from henceforth be printed, bound, stitched, or put to Sale, by any Person or Persons whatsoever, unless the same be first approved of, and licensed under the Hands of such Person or Persons as both or either of the said Houses shall appoint for the Licensing of the same, and entered in the Register Book of the Company of Stationers, according to ancient Custom, and the Printer thereof to put his Name thereto; and that no Person or Persons shall hereafter print, or cause to be re-printed, any Book or Books, or Part of Book or Books, heretofore allowed of and granted to the said Company of Stationers, for their Relief, and Maintenance of their Poor, without the Licence or Consent of the Master, Wardens, and Assistants of the said Company; nor any Book or Books lawfully licensed, and entered in the Register of the said Company for any particular Member thereof, without the Licence and Consent of the Owner or Owners thereof; nor yet import any such Book or Books, or Part of Book or Books, formerly printed here, from beyond the Seas, upon Pain of forfeiting the same to the respective Owner or Owners of the Copies of the said Books, and such further Punishment as shall be thought fit; and the Master and Wardens of the said Company, the Gentleman Usher of the House of Peers, the Serjeant of the Commons House, and their Deputies, together with the Persons formerly appointed by the Committee of the House of Commons for Examinations, are hereby

authorized and required, from Time to Time, to make diligent Search, in all Places where they shall think meet, for all unlicensed Printing Presses, and all Presses any Way employed in the Printing of scandalous or unlicensed Papers, Pamphlets, Books, or any Copies of Books, belonging to the said Company, or any Member thereof, without their Approbation and Consents; and to seize and carry away such Printing Presses, Letters, together with the Nut, Spindle, and other Materials, of every such irregular Printer, which they find so misemployed, unto the Common Hall of the said Company, there to be defaced and made unserviceable, according to ancient Custom; and likewise to make diligent Search, in all suspected Printing-houses, Warehouses, Shops, and other Places, for such scandalous and unlicensed Books, Papers, Pamphlets, and all other Books, not entered nor signed with the Printer's Name as aforesaid, being printed or reprinted by such as have no lawful Interest in them, or any Way contrary to this Order; and the same to seize and carry away to the said Common Hall, there to remain till both or either House of Parliament shall dispose thereof; and likewise to apprehend all Authors, Printers, and other Persons whatsoever, employed in compiling, printing, stiching, binding, publishing, and dispersing, of the said scandalous, unlicensed, and unwarrantable Papers, Books, and Pamphlets, as aforesaid, and all those who shall resist the said Parties in searching after them; and to bring them before either of the Houses, or the Committee of Examinations, that so they may receive such further Punishments as their Offences shall demerit; and not to be released until they have given Satisfaction to the Parties employed in their Apprehension, for their Pains and Charges, and giving sufficient Caution not to offend in like Sort for the future; and all Justices of the Peace, Captains, Constables, and other Officers, are hereby Ordered and Required to be aiding and assisting to the aforesaid Persons, in the due Execution of all and singular the Premises, in the Apprehension of all Offenders against the same; and, in case of Opposition, to break open Doors and Locks: And it is further Ordered, That this Order be forthwith printed and published, to the End that Notice may be taken thereof, and all Contemners of it left unexcuseable."

House of Lords Journal Volume 6

14 June 1643

Briefly, the law 1) establishes a monopoly of approved printers 2) reinforces the traditional Stationer's List 3) gives Parliament the right and duty to search and destroy unlicensed papers and presses 4) and to further search for scandalous or unlicensed books and carry them away 5) to arrest authors, printers, stichers, binders, and sellers of such books 6) and gives them the right to break in to search any premises. The law uses the same tactics developed under the Star Chamber and applies them universally. Milton, a supporter of the Republic, must have been outraged to see the replacement of one tyranny for another. He wrote Areopagitica in spite of the very last line where it is made unlawful to call the law into question. He had to publish without a license and had difficulty finding a printer.

In

the preface of the 1738 edition the editor writes "Is it possible that any

Free-born Briton, who is capable of thinking, can ever lose all Sense of

Religion and Virtue, and of the Dignity of human Nature to such a degree, as

to wish for that universal Ignorance, Darkness, and Barbarity, against which

the absolute Freedom of the Press is the only Preservative?" Milton

would appreciate this as a preface to his work. He said something

similar when he quoted "This is true liberty, when

free-born men, Having to advice the public, may speak free..."

Euripid. Hicetid. at the opening of Areopagitica.

In

the preface of the 1738 edition the editor writes "Is it possible that any

Free-born Briton, who is capable of thinking, can ever lose all Sense of

Religion and Virtue, and of the Dignity of human Nature to such a degree, as

to wish for that universal Ignorance, Darkness, and Barbarity, against which

the absolute Freedom of the Press is the only Preservative?" Milton

would appreciate this as a preface to his work. He said something

similar when he quoted "This is true liberty, when

free-born men, Having to advice the public, may speak free..."

Euripid. Hicetid. at the opening of Areopagitica.

The post publication censorship issue is a little bit tricky. Milton didn't include everyone under the same umbrella. It's ironic, given that this has come to represent, as the preface suggests, this work of great liberty, that Milton had his own intolerances. He is not tolerant of popery for instance. If you were a Roman Catholic writing in support of shifting back or urging others to do so, Milton believed it would be permissible to stamp it out before it could see the light of day "...as it extirpates all religions and civil supremacies, so itself should be extirpate..." He refers to the Inquisition and his prejudice is more a matter of politics than of religion. The arguments with the Catholic Church during this period were not about truth and belief but about power and supremacy.

Milton

began Areopagitica with a series of precedents, proposing that

censorship is a fairly recent development. Even among the early

Christians Milton said: "The books of those whom they took to be grand

heretics were examined, refuted, and condemned in the general Councils; and

not till then were prohibited, or burnt, by authority of the emperor."

The books were read and thought about, THEN they were burnt. At least

they would read over the ideas and digest them before condemning them.

Milton

began Areopagitica with a series of precedents, proposing that

censorship is a fairly recent development. Even among the early

Christians Milton said: "The books of those whom they took to be grand

heretics were examined, refuted, and condemned in the general Councils; and

not till then were prohibited, or burnt, by authority of the emperor."

The books were read and thought about, THEN they were burnt. At least

they would read over the ideas and digest them before condemning them.

He then traced the idea of licensing to "those whom ye will be loath to own" -- the Catholics. You would not want to identify yourselves with these, you would not want to associate yourselves with them. Next he considered the general nature of reading. This section is more theoretical, a discourse on what books are and how they ought to be treated and whether they should be treated any different than anything else. Then he moved onto the practicality of the licensing law. He pointed out that even if it were a good idea, which he doesn't, it would still be impossible to enforce. Finally, he discussed how licensing would harm English political and religious reformation.

Let's take a closer look at these major points. As far as the precedents go, he pointed to the Inquisition and said that they "rake through the entrails of many an old good author, with a violation worse than any could be offered to his tomb." In contrast he drew attention through classical allusions to the ideal of Greece. The very title itself refers to Ares Hill where the council of Athens met. In Athens, he said, there were only two sorts of writings that were punished: the sort that were blasphemous and those that were libelous and took someone's reputation away. In Rome, even Critolaus, by that he meant the "dirty" poets, were allowed to write. It was only when Rome turned to tyranny that books were silenced.

He wanted the members of Parliament to see England as a sort of culmination of classical learning. It was the idea that they were on the cusp of some radical shift in history. The people at that time saw significance in numerology -- 1666 was coming up, a year of unique importance. It was the way we felt about Y2K but more so. Of course, 1666 was, in fact, a very bad year. The Great Fire of London broke out. It is also the year in which all Roman numerals are used and used only once -- MDCLXVI -- and in a descending sequence.

For Milton it meant that this is a crucial time in England. There was enormous intellectual activity. He believed that England was "a nation not slow and dull, but of a quick, ingenious and piercing spirit, acute to invent, subtle and sinewy to discourse, not beneath the reach of any point the highest that human capacity can soar to. Therefore the studies of learning in her deepest sciences have been so ancient and so eminent among us, that writers of good antiquity and ablest judgment have been persuaded that even the school of Pythagoras and the Persian wisdom took beginning from the old philosophy of this island."

He

then went on to talk about the importance of books and pointed out that "To

the pure, all things are pure; not only meats and drinks, but all kind

of knowledge whether of good or evil; the knowledge cannot defile, nor

consequently the books, if the will and conscience be not defiled." It

is not the books or the ideas that are bad, it is up to the pure at heart to

discern which are good. Further, bad books have merit in that "Bad

meats will scarce breed good nourishment in the healthiest concoction; but

herein the difference is of bad books, that they to a discreet and judicious

reader serve in many respects to discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to

illustrate." He pointed out that a scientist does not abandon earlier

incorrect books or theories but delves into them for lessons for the future.

To squelch error, to suppress bad books is to run away from the

confrontation that allows one to become independently the self and find

truth.

He

then went on to talk about the importance of books and pointed out that "To

the pure, all things are pure; not only meats and drinks, but all kind

of knowledge whether of good or evil; the knowledge cannot defile, nor

consequently the books, if the will and conscience be not defiled." It

is not the books or the ideas that are bad, it is up to the pure at heart to

discern which are good. Further, bad books have merit in that "Bad

meats will scarce breed good nourishment in the healthiest concoction; but

herein the difference is of bad books, that they to a discreet and judicious

reader serve in many respects to discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to

illustrate." He pointed out that a scientist does not abandon earlier

incorrect books or theories but delves into them for lessons for the future.

To squelch error, to suppress bad books is to run away from the

confrontation that allows one to become independently the self and find

truth.

He came to the core of his argument when he said, "Good and evil we know in the field of this world grow up together almost inseparably; and the knowledge of good is so involved and interwoven with the knowledge of evil, and in so many cunning resemblances hardly to be discerned, that those confused seeds which were imposed upon Psyche as an incessant labour to cull out, and sort asunder, were not more intermixed." Good and evil are hard to tell apart. Who is going to do this unless they have the opportunity to learn the difference? What happens if you refuse the confrontation? Milton answered, "I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary but slinks out of the race, where that immortal garland is to be run for, not without dust and heat. Assuredly we bring not innocence into the world, we bring impurity much rather; that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary." So if you live in isolation and do not seek the truth, you do not have purity because you have never been tempted. You have only ignorance.

He raised the practical objections that Parliament might have concerning the fear that infection might spread so controversy must be stopped. Milton responded "but then all human learning and controversy in religious points must remove out of the world, yea the Bible itself; ..." If you are going to try to censor bad books because they might infect then you can't stop there. Milton continued, "It will ask more than the work of twenty licensers to examine all the lutes, the violins, and the guitars in every house; they must not be suffered to prattle as they do, but must be licensed what they may say. And who shall silence all the airs and madrigals that whisper softness in chambers? The windows also, and the balconies must be thought on; there are shrewd books, with dangerous frontispieces, set to sale; who shall prohibit them, shall twenty licensers?" If you want to control infection, you have to rid yourself of every idea not only in books but in music and thought itself. It will require an army of bureaucrats. Who is going to keep the bureaucrats pure? As they go about finding bad thoughts, will they not spread the infection? Using wry humor he pointed out that "And he who were pleasantly disposed could not well avoid to liken it to the exploit of that gallant man who thought to pound up the crows by shutting his park gate."

In his last chapter he talked about his travels abroad and his meeting with Galileo. He talked about the fact that everywhere he went people envied the fact that he lived in England. What a great place it must be to be able to say what you think. "I could recount what I have seen and heard in other countries, where this kind of inquisition tyrannizes; when I have sat among their learned men, for that honour I had, and been counted happy to be born in such a place of philosophic freedom, as they supposed England was, while themselves did nothing but bemoan the servile condition into which learning amongst them was brought; that this was it which had damped the glory of Italian wits; that nothing had been there written now these many years but flattery and fustian." Milton had heard the same complaints on the continent as he was hearing then in England. The Inquisition was simply recycling these Roman Catholic atrocities.

"Truth

is compared in Scripture to a streaming fountain; if her waters flow not in

a perpetual progression, they sicken into a muddy pool of conformity and

tradition. A man may be a heretic in the truth; and if he believe things

only because his pastor says so, or the Assembly so determines, without

knowing other reason, though his belief be true, yet the very truth he holds

becomes his heresy." Milton continued the argument with an ancient

example: "Truth indeed came once into the world with her divine

Master, and was a perfect shape most glorious to look on: but when he

ascended, and his Apostles after him were laid asleep, then straight arose a

wicked race of deceivers, who, as that story goes of the Egyptian

Typhon with his

conspirators, how they dealt with the good

Osiris, took the virgin

Truth, hewed her lovely form into a thousand pieces, and scattered them to

the four winds. From that time ever since, the sad friends of Truth, such as

durst appear, imitating the careful search that Isis made for the mangled

body of Osiris, went up and down gathering up limb by limb, still as they

could find them. We have not yet found them all, Lords and Commons, nor ever

shall do, till her Master's second coming; he shall bring together every

joint and member, and shall mould them into an immortal feature of

loveliness and perfection." Truth is a process of progressive

revelation. To get from one point to another you have diverge from the

path you are supposed to be on. He included the "schisms and sects" of

different approaches to religion in the legitimate search for truth.

"Truth

is compared in Scripture to a streaming fountain; if her waters flow not in

a perpetual progression, they sicken into a muddy pool of conformity and

tradition. A man may be a heretic in the truth; and if he believe things

only because his pastor says so, or the Assembly so determines, without

knowing other reason, though his belief be true, yet the very truth he holds

becomes his heresy." Milton continued the argument with an ancient

example: "Truth indeed came once into the world with her divine

Master, and was a perfect shape most glorious to look on: but when he

ascended, and his Apostles after him were laid asleep, then straight arose a

wicked race of deceivers, who, as that story goes of the Egyptian

Typhon with his

conspirators, how they dealt with the good

Osiris, took the virgin

Truth, hewed her lovely form into a thousand pieces, and scattered them to

the four winds. From that time ever since, the sad friends of Truth, such as

durst appear, imitating the careful search that Isis made for the mangled

body of Osiris, went up and down gathering up limb by limb, still as they

could find them. We have not yet found them all, Lords and Commons, nor ever

shall do, till her Master's second coming; he shall bring together every

joint and member, and shall mould them into an immortal feature of

loveliness and perfection." Truth is a process of progressive

revelation. To get from one point to another you have diverge from the

path you are supposed to be on. He included the "schisms and sects" of

different approaches to religion in the legitimate search for truth.

In Paradise Lost Milton expresses his idea of free will as God having made man

All he could have; I made him just and right,

Sufficient to have stood, though free to fall.

Book 3

Truth is a continual process of choice, the choice to confront, to choose and to move on.

Milton portrait from University of Texas collection

Following an extensive question period, members of the audience had the opportunity to examine the 1738 edition of Areopagitica. Click on images below for larger versions.

|

|

|