|

| The earliest calendars can be traced to the Neolithic period, but it is only with the beginning of the dynastic period that calendars were standardized and formalized. From the Shang Dynasty (1523-1027 BC) to the Warring States Period (770-221 BC) there was continuous improvement in observation and thus the calendar improved. All of the calendars were based on the average motion of the moon and measured a month as starting and ending with the new moon. Oracle bones show that during the Shang Dynasty people used a year of 365 days and a lunar month of about 29 or 30 days. It was during the Warring States Period that the 24 Seasonal Segments (二十四节气 èrshísì jiéqì) were incorporated into the calendar.

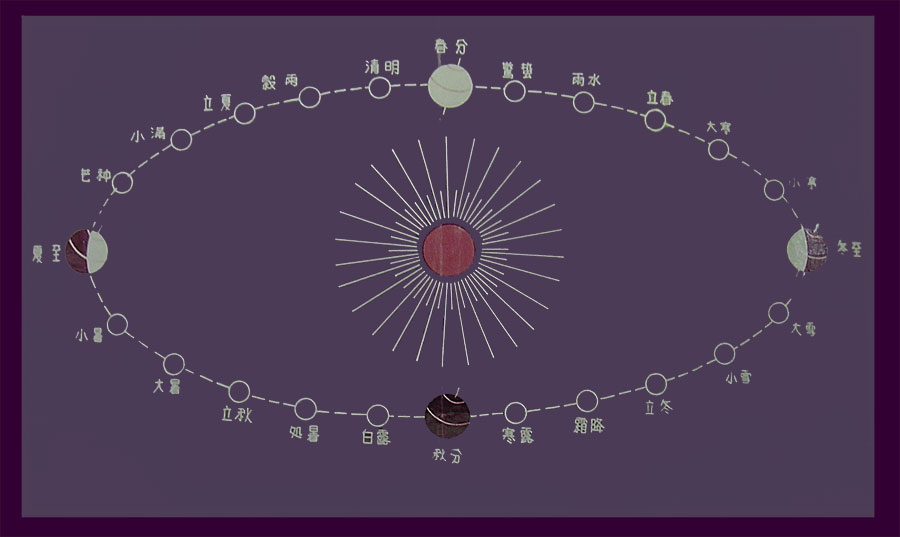

The sky is divided into 24 segments or jiéqì (节气) based on the seasons of the year. The earliest calendars assumed that the motion of the sun was constant and divided the year into 24 segments with equal numbers of days. This method is called píngqì (平气). Because the motion of the sun is not consistent, this was found to be inaccurate. The calendar then changed to a method where the ecliptic (the path of the sun as seen from earth) was divided into 24 equal parts of 15 degrees. This method is called dìngqì (定气). Calendars from the Warring States Period through the Ming Dynasty used the pingqi method in their designs and only changed to the more accurate dingqi method during the Qing Dynasty. The average lunar month is a little more than 29 and 1/2 days. It is the half day that is a problem. The solution was to have both short (29 days) and long months (30 days). The procedure works for a short time but eventually gets out of step with the new moon because the lunar month is slightly longer than 29.5 days. To correct that, periodically a double long month would be added to the calendar to bring the beginning of the month back to the new moon. The leap concept was also used to bring the calendar back to agreement with the year. An average of 29.5 days in 12 months only gives you 354 days in a year. Every few years, an extra month called an intercalary month would be added to make up the days needed to keep the solstices and equinoxes consistent with the seasons. During the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), Jiǎ Kuí 贾逵 observed that the motion of the moon was actually inconsistent, but he continued to use the pingqi method of calculation in his Sì Fèn calendar (四分历). In 223 AD Kàn Zé (阚泽) used the dingqi method to predict eclipses but still based his Qian Xiang calendar on the pingqi method. Subsequently, several calendars were proposed (from the Yuan Jia calendar in 445 AD through the Wu Yin calendar in 619 AD) that incorporated the dingqi method. In each case the imperial court refused the innovation because the procedure would include more than two long months in a sequence. It is amazing that a culture that regularly required its astrologers to rewrite the calendar would hold on so tightly to the simple rule of the pingqi calendars, "Never more than two long months in a row," but they did. The relationship between our view of stability and the mythology we create around time is deep seated. We happily deal with uneven months and leap years, but if it were seriously proposed that we straighten the whole thing out, there would be riots in the streets as there were when the Gregorian calendar was introduced. It is not logical that we cling to something that is just a concept, but we do. As a consequence, calendars could be "reset", but they had to use the same rules. Although future astronomers continued to use the dingqi calculation to develop their calendars and to make observations after the Qian Xian calendar, it wasn't until the Qing Dynasty that it was actually built into the calendar. All of the earlier calendars were based on the pingqi method. Below is a table of the 24 seasonal segments shown in the picture above. They are based on the idea of predicting the seasonal variation using the moon's motion to measure the time it will take for the earth to return to a certain position (the solstices and equinoxes) in relation to the sun. Thus, the Chinese calendar is a lunisolar model. Below that is a partial list of some of the calendars in Chinese history. A few will be discussed in greater depth on subsequent pages. |

| 1 Li Chun 立 春 2 Yu Shui 雨 水 3 Jing Zhe 惊 蛰 4 Chun Fen 春 分 5 Qing Ming 清 明 6 Gu Yu 谷 雨 7 Li Xia 立 夏 8 Xiao Man 小 满 9 Mang Zhong 芒 种 10 Xia Shi 夏 至 11 Xiao Shu 小 暑 12 Da Shu 大 暑 13 Li Qiu 立 秋 14 Chu Shu 处 暑 15 Bai Lu 白 露 16 Qiu Fen 秋 分 17 Han Lu 寒 露 18 Shuang Jiang 霜 降 19 Li Dong 立 冬 20 Xiao Xue 小 雪 21 Da Xue 大 雪 22 Dong Zhi 冬 至 23 Xiao Han 小 寒 24 Da Han 大 寒 |

Beginning of spring (Spring Festival) Rain water Waking of insects Spring equinox (March 21) Pure brightness Grain rain Beginning of summer Grain full Grain in ear Summer solstice (June 22) Slight heat Great heat Beginning of autumn Limit of heat White dew Autumnal equinox (September 23) Cold dew Descent of Frost Beginning of winter Slight snow Great snow Winter solstice (December 22) Slight cold Great cold |

|

A Minor Sample of the 102 Calendars in Chinese History

|

|||||||

| Calendar | 汉字 | Year | Astronomer | 汉字 | Dynasty | Span | Notes |

| Xià Xiǎo Zhèng | 夏小正 | 16th century BC |

Xia | 2070-1600 BC | Divided the year into 12 months, comments on agriculture and weather observations | ||

| Lǔ lì | 鲁历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Zhōu lì | 周历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Yīn lì | 殷历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Xià lì | 夏历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Zhuān xū lì | 颛顼历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Huángdi4 lì | 黄帝历 | Warring States | 770-221 BC | Pingqi method developed in Warring States | |||

| Sì Fèn | 四分历 | 85 AD | Jiǎ Kuí | 贾逵 | Eastern Han | 25-220 AD | Discovered motion of the moon was inconsistent, based calendar on pingqi |

| Qián Xiàng | 乾象历 | 223 AD | Kàn Zé | 阚泽 | Three Kingdoms | 220-280 AD | Dingqi used to calculate eclipses but based calendar on pingqi |

| Yuán Jiā | 元嘉 历 |

445 AD | Hé Chéngtiān | 何承天 | Northern and Southern |

386-589 AD | Using dingqi found that could have strings of 3 and 4 long or short months - not implemented due to political constraints |

| Zhāng Zǐxìn | 张子信 | Northern and Southern |

386-589 AD | Discovered inconsistent speed of the sun | |||

| Dà Míng | 大明历 | 510 AD | Zǔ Chōngzhī | 祖冲之 | Northern and Southern |

386-589 AD | Measured precession of the earth's axis - sui cha (岁差) |

| Wǔpíng | 武平历 | 576 AD | Líu Xiàosūn | 刘孝孙 | Sui | 586-618 AD | Included a correction for the Sun's variable movement and solar center - not an official court calendar |

| Kāi Huáng | 开皇历 | 589 AD | Zhāng Bīn | 张宾 | Sui | 586-618 AD | Inferior calendar written by a monk who was not an astronomer which replaced the Da Ming and ignored precession and the changing solstice point |

| Dàyè | 大业历 | 596 or 597 AD | Zhāng Zhòuxuán | 张胄玄 | Sui | 586-618 AD | Included a linear interpolation to estimate the Sun's changing speed |

| Huáng Jí | 皇极历 | 600 AD | Líu Zhuō | 刘焯 | Sui | 586-618 AD | Discussed inconsistent speed of the sun, but thought the changes were sudden |

| Wù Yín | 戊寅历 | 619 AD | Fù Rénjūn | 傅仁均 | Tang | 618-907 AD | Dingqi showed string of 4 long months, so again used pingqi - (Fu Renjun also worked during the previous Sui Dynasty) |

| Lín Dé | 麟得历 | 665 AD | Tang | 618-907 AD | Dingqi in the form of dingshuo became the common method for calculation - but still not the base of the calendar | ||

| Dà Yǎn | 大衍历 | 729 AD | Sēng Yī Xíng | 僧一行 | Tang | 618-907 AD | Corrected Zhāng Zhòuxuán and Líu Zhuō 's measurement of solar speed. Determined the actual movement of the Sun and used it to calculate eclipses but not in calendar. Still used pingqi |

| Fútiān | 符天历 | 780 AD | Cáo Shìwéi | 曹士为 | Tang | 618-907 AD | Parabolic interpolation for solar motion |

| Qīntiān | 钦天历 | 956 AD | Wáng Pǔ | 王朴 | Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms |

907-979 AD | Used Yixing's meridian line to create a new algorithm of the Sun's shadow. |

| Shòu Shí | 授时历 | 1281 AD | Guō Shǒujìng | 郭守敬 | Yuan | 1279-1368 AD | Refined the measurement of the precession of the earth's rotation |

| Shí Xiàn | 时宪历 | 1645 AD | Adam Schall von Bell | 汤若望 | Qing | 1645-1911 AD | Ding qi and procession measures implemented in the calendar. Added calculation of Changed day from 12 hours (时辰) with 100 quarters to 24 hours and 96 quarters of 15 minutes. Added time zones for calculation of dawn, dusk and jie qi (seasonal segments), jie qi set at 15 degrees of the ecliptic. |

http://hua.umf.maine.edu/China/beijing2.html

Last update: May 2007

© Marilyn Shea, 2007