Henry II -- King of England (1154 - 1189) Richard I -- King of England (1189 - 1199) John -- King of England (1199 - 1216) Henry III -- King of England (1216 - 1272) Magna Carta, 1215

King John is familiar to most people through the Hollywood version of the legend of Robin Hood. He is portrayed as second only to the Sheriff of Nottingham in cunning and treachery. In the Robin Hood tales, John plots to prevent Richard Lionheart from returning to England and to the throne which is rightly his. Robin is engaged in the practice of robbing the rich to give to the poor, mainly because King John has set extraordinary taxes and given the Sheriff extreme powers to collect them. In essence, that was the situation. But Robin Hood does not enter our story at all. There is little evidence to place him on the scene, the best documented legends place him several hundred years in the future. The historical version differs from that described by myth but is even more dramatic.

There were eight children of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine: William (1153 - 1156), Henry (1155 - 1183), Matilda (1156 - 1189), Richard (1157 - 1199), Geoffrey (1158 - 1186), Eleanor or Leonora (1162 - 1214), Joan (1165 - 1199), and John (1166 - 1216). There were also half-brothers and half-sisters from Eleanor's first marriage and Henry II's relationships, but the story is complicated enough without including them. Let's just say that they did rather well for themselves and leave it at that.Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine had a dysfunctional marriage marked by rivalry for power, conspiracy, plotting, and Henry's wandering eye. Eventually this led to the imprisonment of Eleanor. The children in the immediate family reflected their parent's politics and problems. The oldest son, William, died when he was three and the next in line, Henry, was actually crowned king, but never ruled. He died six years before his father. For that reason he is called Henry the Young King and doesn't get to have a roman numeral. Richard was next in line and became Richard I upon the death of his father in 1189. Sounds simple and reasonable so far. It wasn't. Henry II wanted John to become king but was hampered by details called tradition and law. In addition, Eleanor had made Richard her heir. Henry II wanted control over Eleanor's holdings, and in the end Eleanor unsuccessfully plotted with her other children to overthrow Henry II, or to at least wrest control over most of the French territories from Henry II. But that gets ahead of the story.

Henry II of England from Cassell's History of England - Century Edition - published circa 1902Let's go back a bit. Henry's great-grandfather on his mother's side was William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy. When William won the battle of Hastings and the English crown in 1066, he maintained his lands in Normandy and remained the Duke of Normandy. By the time of Henry II, not only did Henry rule Normandy, but Anjou as well. When he married Eleanor, she brought Touraine, Aquitaine, and Gascony into the family. Add in Maine and Poitou and that gave Henry II power over much of France. But France had a king, Louis VII, who, just to make the story more complicated, had been Eleanor's first husband. Not surprisingly, Henry II was a threat to the French king, and Henry II had to defend his territories. He did so successfully in 1152 but we shall see that the French didn't give up. This gets complicated. The French territories were not part of England. While King of England, Henry remained Duke of Normandy and had various other titles for his other holdings within the French court. He owed fealty duty to the king of France.

Henry II

Henry II was king for over thirty years and during that time worked to modernize his administration and kingdom. As he increased the power of the state, he came into conflict with the other power in England and Europe: the Catholic Church. Two of the most important functions of government are keeping the peace and providing common resources such as an army. To do either of those, one must have money which can be gotten in a number of ways.

Henry II was as interested in strengthening his power in England as he was in maintaining his French possessions. He instituted a number of reforms in England to bring the power of the king to remote regions and protect his borders. He began to travel to various parts of England to assess conditions, hold court, and generally establish rule. Dukes, left to their devices, tended to get ambitious. More important, he created new law through the Assize of Clarendon (1164) which arranged for regular court visits to settle disputes, particularly land disputes. Judges were appointed who had the power of the crown behind them. They traveled around England holding assizes, what we, in America, would call a circuit judge. They replaced the courts controlled by the Catholic Church.

Historical map of France - 1154 to 1184 showing English holdings, from Shepherd. 1911. Courtesy Univ. of Texas LibrariesPart of their procedure was to call together 12 men who were knights to use their memory of who owned what to settle disputes. This was the beginning of trial by jury. In addition, there was a larger court that might visit only once every seven years. It also used local knights to evaluate claims as in a Grand Jury. The system wasn't complete, but it was a beginning. The power of law was taken from the local Dukes and from the Catholic Church.

This move on Henry's part brought him in direct confrontation with the Church. Not only would the Church lose the power of being primary arbiter in all sorts of civil cases, Henry II demanded that the members of the clergy subject themselves to the civil court for civil matters. If there was a land dispute between the Church and a local landowner, the civil courts would have jurisdiction. If a priest were caught stealing, the civil courts would have jurisdiction. Up to this point, the Church had handled all such matters. It was as if they were a separate country operating by the laws of Rome. Or a modern analogy might be that every priest and nun had diplomatic immunity.

Thomas Becket

It happened that Henry II had the opportunity to appoint a new Archbishop of Canterbury. This is how closely related the Church and state were in those days. The Church had power in civil affairs, but Henry had the power to appoint archbishops. To make sure that he had someone who would support his new reforms, he appointed one of his best friends, Thomas Becket (who would be called Thomas à Becket after his death).

Bell Harry Tower, Canterbury Cathedral. Wood engraved print published in Picturesque Europe, circa 1875. Courtesy of Steve BartrickThomas was not in the clergy, he was the Chancellor. To correct this minor problem, he was ordained as a priest, the following day was made a bishop, and by evening, became the Archbishop of Canterbury. Who says there isn't humor in history?

At first everything went well. Thomas supported Henry's new laws. Gradually though, as Thomas grew into his new position, he began to have pangs of conscience and, as often happens, because of his new responsibilities he began to adopt the point of view of the Church and the need to protect it and its integrity. He became extremely religious. Historically this era is the beginning of a long process of separating the powers of church and state. It wasn't easy to draw the line; it still isn't today. During the feudal era the Church was so strong and provided so many benefits and services to the kings of various countries there wasn't much question of the necessity of cooperation.

That began to change as nationalism increased, educational levels outside the monasteries increased, and the kings coalesced their power. The Church was a threat; at the same time it ensured an umbrella of international cooperation. The pope can be seen as meddlesome on the one hand, but on the other hand he worked to maintain peace to preserve communication and his own supra-national organization. He used the power of the Church to excommunicate disobedient kings or in extreme cases he used the power of the interdict; denying an entire populace the sacraments and clergy. Kings ruled by the grace of God and the pope was his messenger. Almost anything could be interpreted as impacting the welfare of souls and thus would come under the purview of the Church.

The balance of power for the kings was their control of the military, the economy, and the loyalty of their subjects. More sophisticated government, taxation, record keeping, and bureaucracy strengthened the king and made the support of the Church less necessary for the survival of the state. The increased importance of real property, trade, and travel called for more civil authority to maintain and defend it. The need for a military, used both to defend and expand territory, also increased as the nations became more organized and prosperous and thus more desirable as prizes of war.

This then is the situation facing two friends. Thomas Becket and Henry II were both intelligent rulers who could see the patterns of social power and history. Each was called on to protect the future of their convictions. In 1163, a member of the clergy was acquitted of a murder charge by the Church court. The people were angry and Henry tried to have the man brought before the civil court. That was when Thomas chose to oppose him. History is fickle because people are fickle. The scandals of preference and bribery dogging the Church court were not limited to this case. In the interest of justice, Henry II had established a system which would, as far as possible in those days, not depend on wealth, connections, or position. Thomas might have chosen a better case on which to make his stand, but in the end it didn't matter -- the people changed sides and supported him once Henry went into action.

When Thomas opposed Henry's civil courts, Henry retaliated and began the process of "setting him up" for misuse of government money during Thomas' tenure as Chancellor and Archbishop. Thomas Becket fled to France and the protection of Louis VII. Once there, he further angered Henry by excommunicating two bishops who were supportive of Henry's new policies. He stayed in France for seven years. In 1170 Henry II came to France and the two met in Normandy. Henry had heard that Becket was trying to get the pope to excommunicate him. As the result of this meeting and the backing of Pope Alexander, Thomas Becket returned to Canterbury. Henry was still in France when he got the news that Thomas had refused to rescind the excommunication of his bishops. He lost his temper and four of his knights heard him say, "Who will rid me of this meddlesome priest?" According to Henry II, they took it upon themselves, without his knowledge, to do the deed. You can read a vivid eyewitness account of the murder of Thomas Becket written by Edward Grim, a monk of the cathedral, if you go to the reference at the bottom of this page.

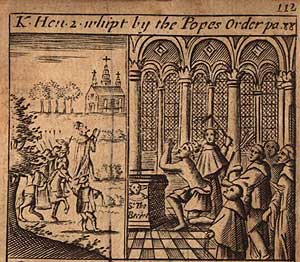

The murder had far-reaching consequences for England, but the immediate result was that Henry II had to make peace with the Church. He did this four years later by performing penance at Canterbury Cathedral. He was beaten by eighty monks while wearing sack cloth and ashes and spent the night in vigil at Saint Thomas Becket's tomb. The Church had wasted no time and had canonized Becket in 1173. He also had to promise to raise money for the Crusades and to either mount a Crusade or make a pilgrimage. He did neither. There was enough to do at home.

"King Henry II whipt by the Pope’s Order" in Wonderful Prodigies of Judgment and Mercy, 1685. Courtesy Liam Quin's Pictures From Old Books Web site.In 1173 Henry II's son Henry the Young King, with the support of Richard and Geoffrey started a revolt against their father. While young Henry had been made king, he had no power and very little money. Richard and Geoffrey also stood to benefit by freeing themselves from the control of their father. The group had quite a bit of support from nobility both in their French territories and in England, including young Henry's father-in-law, Louis VII of France. But Henry II handily won the day, both in England and when he took his armies to France. Henry forgave his sons, but it would seem that in this case Thomas Becket was right. He had strongly advised against the coronation of young Henry. It creates a terrible situation when there are two kings – even if one of them is your son. Monarchies have always had the problem of what to do with adult heirs to the crown. Henry the Young King died in 1183 during another revolt against his father.

While all this was going on, Henry II took the opportunity to expand his territory to the west. In 1169, Henry II was requested to send troops to aid Dermot MacMurrough who claimed the crown of Ireland. Ireland was, at that time, split up into small dukedoms and kingdoms with a high king. There were many candidates for the post, but no one had significantly greater resources. Henry II changed that. The throne was secured in 1169, but MacMurrough requested more and more troops to keep the peace. When he died in 1171, the Anglo-Norman troops were already loyal to Henry II and he sent additional troops and claimed Ireland for himself. This was quite a coup for a king, in fact, it was just about a bloodless coup. Historically, it may have cost more than it was worth, but at the time it seemed like a good idea.

In 1185 Henry II sent his youngest child, John, to be Lord of Ireland. John is nicknamed Lackland because when all of the duchies and provinces were parceled out, he inherited nothing. Ireland seemed a good solution for this, Henry's favorite child. It wasn't. John was only 19 at the time, and an Ireland which was torn by civil war was not the place to learn statesmanship. The Irish resented the presence of the English, more so because of the policies John was charged with implementing. Had John been older and wiser, he might have brought peace and settled the disputes which had torn the country apart. External rulers were sometimes invited in to do just that. But that had not been Henry's plan. John often acted immature, but he also accomplished a great deal. His primary goal was to place power and land into the hands of those loyal to Henry. He did this. His popularity declined as did his funds and when he ran out of cash, he returned to England. He might have returned but by then the situation in England was stressed.

Henry II, to raise money for the Crusades and keep good relations with the Church, had increased taxes. The treasury was already stretched by the defense of his territories in France. Domestic problems within the family had continued. Henry probably wanted John close to him. It didn't help. In 1189, his son Richard aided by Philip II Augustus of France, again attacked him. This time Henry lost and made a humiliating peace with Richard. As part of the deal he made Richard heir to the English throne. Two days later, Henry II died a natural death at the age of 56 and Richard became Richard I. That left John out in the cold. He married the same year, but he held only a few castles and titles, but no real rights.

Here's the situation so far:

• Henry has established a rule of law, trial by jury, and a bureaucracy.

• Henry has alienated the Church and had to make major concessions to prevent interdiction and excommunication.

• For the moment, the Church had managed to strengthen its position and popularity.

• Taxes had increased drastically and most of the money sent to Jerusalem or spent on actions in France.

• France is biting at the heals of England due to the amount of territory held by the English king.

• The family is much simpler now, both young Henry and Geoffrey have died. There is only the young and assumed to be ineffectual John.Richard I

Richard I (called Lionheart) wasn't very interested in England. He had spent his life in France and his rebellions against his father had been to wrest control of, and gain the income from the French territories from his father. He was a soldier, above all. His manner of administration in France was to gather together some knights and a small army and pound on rebellious areas in his domains. It was effective, but didn't win him popularity contests.

Rather than staying in England and building the country and continuing his father's work, Richard I decided to use the money raised for the Crusades and additional money he raised by selling off anything that wasn't tied down and go off to the Holy Land to fight some real battles. There is no glory for a soldier in sitting in a castle doing paperwork. He was good at military strategy and enjoyed it. He was clever enough to realize that if he left John and Philip II of France behind, he would have nothing to return to.

Crusaders attack a castle. The man behind the wounded soldier wears a crown, and his hauberk bears the three lions of England. from The World's Best Music eds. H. K. Johnson, F. Dean, R. DeKoven and G. Smith, Vol I, The University Society, New York, 1900. Courtesy Liam Quin's Pictures From Old Books Web site.He convinced Philip II to join him on the Crusade and made John promise to stay out of England for three years. In return he gave John additional estates and titles. He appointed people to be in charge of his various holdings and with Philip II set off with his army. To make a long story short, he was very successful in his campaigns until Philip II decided that he had to go back to France and abandoned him. Richard I simply didn't have the manpower to recapture Jerusalem and at that point turned back to go home. He was shipwrecked, captured in Austria, and held for ransom.

In the meantime, back in England, John had not been sitting on his hands. Richard I was away for years. John plotted to take over and did manage to take over as regent. That part of the modern Robin Hood picture of the situation was fairly accurate. But notice that the punitive taxation was actually Henry and Richard's doing. When Philip II returned he joined in an alliance with John to replace Richard I. This plan looked more hopeful on news that Richard I had been captured and was being held for ransom. It must have been tempting for John to just let history take its course. But Eleanor, his mother, was still alive and still a major power. She raised much of the money for the ransom and John ordered additional taxes to be raised to pay for it. The ransom was enormous, 150,000 marks in silver. It was at least as large as the amount raised by the tithe of 10% for the Crusades in the first place. In 1194 the ransom was paid and Richard I returned home. John was forgiven but removed from government.

Richard I immediately set off for France to fight Philip II to regain his lands. To do so, he had to raise yet more money for his army. It took four years to drive Philip II out and suppress rebellious areas. Most of the money was raised in England to fight this war. It is difficult to collect taxes in areas under someone else's control. By 1199 Richard I was in pretty good shape, having defeated the French and secured his territory, but when fighting a minor skirmish he was wounded in the shoulder and developed gangrene. His mother, Eleanor was at his bedside. Before he died, he designated John as heir to the throne.

• Richard I had secured the French lands, but in the case of might makes right, it only applies to your lifetime.

• Relations with the Church should have been better, Richard won major battles on the Crusades and signed a treaty with Saladin that made it easier for pilgrims to visit Jerusalem.

• But he didn't defeat Saladin and came back without riches to replace the treasury.

• Taxes have increased drastically both for the Crusade and the ransom.

• The French campaigns, while successful, strained the treasury and military potential in England.

• The reforms of Henry II made it possible for England to run fairly smoothly in Richard's absences. For ten years the English had found they could get along without a king.

"King John" engraved by Noble after a picture by Wale. Published in History of England, about 1800. Courtesy of Steve BartrickJohn of England

That left John, but it left him in a terrible situation. England was broke, the army was made up of mercenaries and needed to be paid, and Philip II still wanted control of the French territories. To add spice, Arthur, John's nephew and son of Geoffrey, John's older brother, had powerful supporters in France who backed his bid for the throne. John had to increase taxes yet again, this in a country which had been ravaged by his brother's military needs. To raise an army he increased the scutage again, the amount of money you could pay to avoid military service. He sold titles and increased the number and types of tax on forest use, trade, and property. He, too, set off for France. He was able to defeat and capture Arthur, but Philip II was another matter. John was no military commander and the support that John got from the French territories was not that offered to Richard I. Richard had essentially been one of them. John lost territories one by one.In 1201 John sailed to France to put down rebellion among the Lusiganans. In 1202 Arthur was captured as he was besieging a town to try to kidnap Eleanor of Aquitaine. He was delivered to John and died or was murdered in captivity. In 1204 Normandy was lost to the French, but John still had Aquitaine. In 1205 there were rumors of a planned French invasion of England so John had to increase fortifications. The French didn't invade, instead in 1205 the castles at Chinon and Loches in the Loire Valley were taken. Chinon had been built by Henry II and was his favorite residence. (Later it would become famous for the start of Joan of Arc's career.) John tried to make peace, but treachery interfered. In 1206 John sailed to Aquitaine to defend it and managed to gain back some additional land. This led to a short truce. By 1209 there was trouble brewing on the northern border and John took a force from Wales to Scotland where he was able to settle the dispute with William, King of Scotland by treaty rather than war. In 1210 he led an expedition to Ireland to hunt down a rebel Baron. This trip to Ireland was more successful and he received homage from various Chieftains. Between 1210 and 1212 he strengthened his relation with both Wales and Scotland but by 1213 he again had to prepare for invasion from France.

Stephen Langton

John was in trouble on all fronts. The long years of Richard's absence, the extreme taxation to support the Crusade and the ransom, and the continued need to defend and retake the French possessions weakened his position in England. In addition, he was in trouble with the Church. The struggle over church and state had not ended with Henry II. The pope was intent on maintaining power, so was John. Things came to a head when John tried to appoint a new Archbishop of Canterbury in 1205 and the monks wanted someone else. When the dispute was appealed to Pope Innocent III, the pope took the opportunity to appoint his own man; he chose Stephen Langton. John would not accept Langton and by 1207 the pope threatened interdiction unless Langton was received. Remember that Henry II had been able to create Thomas Becket as Archbishop in two days. The argument was about the power over the Church and who controlled the clergy and the lands and wealth of the Church. In 1208 the pope activated the interdiction on England and John retaliated by confiscating Church property. In 1209, Langton actually came to England but John would still not receive him and the pope responded by excommunicating John. Essentially, the pope had taken away the right to rule, not just his religious salvation. Throughout the country, the priests would not perform the sacraments other than baptism and confession due to the interdiction. The excommunication of John meant that he no longer had the divine right to rule and had lost the support of the Church. The Church then swung their support to the French.

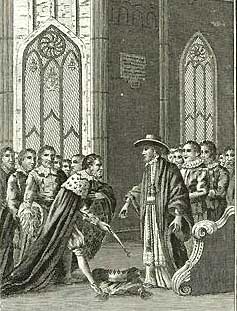

In 1212, John surrendered and sent a mission to the pope. As a result, he had to accept Langton, pay 100,000 marks to the Church (more money), and swear allegiance to the pope. Essentially he pledged England to the pope and ruled it as a fiefdom. In 1214 the interdiction was lifted. At that point, John again traveled to France but was defeated at the battle of Bouvines. The French under Philip II capitalized on their win and invaded England, taking Colchester Castle.

"The Crown resigned to the Pope's Legate by King John" (in 1213), from History of England, about 1800.. Courtesy of Steve BartrickHad this not been yet another emergency in a 15 year series of emergencies, John might have been able to repel them. As it was, the Barons had had enough. They began to rebel and looked to form alliances with France – probably betting that would be the future. There wasn't a lot of faith in John's military talent and the French had landed.

John had been fighting military and religious battles since he came to power. Money was a perennial problem. The coffers were already depleted. Richard's Crusade had had to be paid for and on top of that, the ransom. No profits had been realized by the Crusade, it was a dead loss. Taxes were already high. The scutage had been increased. His challenge of Church authority had failed, and with it another possible source of income. He had cut domestic spending except for fortifications. He had confiscated lands, sold titles, taken what amounted to bribes for certain privileges and generally run rough shod over the niceties of court politics in the interest of efficiency.

Revolt and Demands

The revolt spread. The Barons were able to take control of a number of critical castles. They attacked and occupied London but failed to take the Tower of London. John was forced to capitulate, especially with the French already in Colchester. When the armies of the Barons met John's at Runnymede on June 10, 1215, John had little choice. He could plunge his country into cruel war (which he probably would have lost) or he could negotiate. He negotiated. The demands made by the Barons were primarily for rights they already had but had never been written. They also demanded a tax cap. There are a number of articles in Magna Carta which specify exact amounts allowed for fees and taxes.

Among the new rights demanded was a first step to protect women and children. Marriage was a matter of alliance and property. The King approved all marriages among the peers and in some cases initiated them himself. When a woman was widowed the King had the right to marry her to whomever he pleased. Because the widow came with property, he had able to charge fees to the man who made the highest bid who would then take possession of both the woman and the dower and in the case where there was no heir, the titles and lands. Of course, only supporters of the King need apply. Following Runnymede, a widow could still not marry without the King's permission, but she could not be forced to marry. This gave women a measure of protection and some power. They could remain on their land and manage it for their own profit. Their dower rights were protected. In addition, they could not be forced to move out of their homes for a certain amount of time when their sons inherited following the death of their husbands and they maintained the income from their dowers. There must have been a number of ungrateful sons who tossed their mothers out upon the death of their father to make this of prime importance. Before you reflect on the barbarity of the time, remember that today the person who preys on the wealth of a modern widow is usually the son or daughter.

There were several sections to protect children, more especially the underage heirs of the Barons. If the child was underage, a protector was appointed to manage the estates, but they were not allowed to take more than the management costs and were required to return the estates in working order when the child reached maturity. There were safeguards put in that would trigger procedures if there was skullduggery. The crown was made responsible for fining the perpetrator to replace the damage and for finding two replacements to manage the estate. This must have been a common problem. The powerless minor was easy prey for those administering their estates. It had been a nice source of revenue as administrators simply annexed the property to their own holdings.

There are sections which specify how disputes are to be settled. This is essentially the foundation for trial by jury. The Barons were forcing John to recognize and return to the reforms put in place by his father, Henry II, with the Assizes of Clarendon. They strengthened it by demanding that a council of 25 Barons be allowed to act as council to the king to make sure that the agreements in Magna Carta were observed.

The Barons had specific issues in mind when they met with John at Runnymede. The items within Magna Carta were targeted toward localized grievances, primarily associated with taxation. They were also concerned with what they considered their traditional rights with respect to the king. They did not make broad or generalized demands but rather focused on the immediate.

For instance:

All forests that have been created in our reign shall at once be disafforested. River-banks that have been enclosed in our reign shall be treated similarly.

The Royal Forests were a major source of revenue for the crown. To use the land, locals had to pay exorbitant fees. Hunting was forbidden or by license. Richard and John had added to the forests as a means of increasing revenue but had condemned people to starvation and subsistence as a result. The forest management was rife with graft and corruption and the charter further demanded that ALL foresters and wardens be investigated by twelve sworn knights of the county. They gave them forty days to fix the problem and exact punishment. (See reference below for a description of the Royal Forests).

from Historical Inquires, concerning Forest and Forest Laws, with Topographical Remarks, upon the Ancient and Modern State of the New Forest, in the County of Southampton, by Percival Lewis Esq, Engraved by C. Sheringham for Percival Lewis Esq, 1811. Courtesy Liam Quin's Pictures From Old Books Web site.The first clause of Magna Carta is different. Scholars seem to agree that it was added at the last moment. In it, John agreed to keep his hands off the Church elections, but more, that it would be free in all other ways.

FIRST, THAT WE HAVE GRANTED TO GOD, and by this present charter have confirmed for us and our heirs in perpetuity, that the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired. That we wish this so to be observed, appears from the fact that of our own free will, before the outbreak of the present dispute between us and our barons, we granted and confirmed by charter the freedom of the Church's elections - a right reckoned to be of the greatest necessity and importance to it - and caused this to be confirmed by Pope Innocent III. This freedom we shall observe ourselves, and desire to be observed in good faith by our heirs in perpetuity.

Only then does it go on to address the concerns of the Barons:

TO ALL FREE MEN OF OUR KINGDOM we have also granted, for us and our heirs for ever, all the liberties written out below, to have and to keep for them and their heirs, of us and our heirs: (Quotations from British Library translation, see below)

The inclusion of the article promising independence to the Catholic Church in the first position shows the power the Church had regained in the confrontation over Langton's appointment. It's of interest to note the number of clergy cited as witnesses in Magna Carta:

The clergy mentioned at the beginning of Magna Carta: Stephen, archbishop of Canterbury, Henry archbishop of Dublin, William bishop of London, Peter bishop of Winchester, Jocelin bishop of Bath and Glastonbury, Hugh bishop of Lincoln, Walter Bishop of Worcester, William bishop of Coventry, Benedict bishop of Rochester, Master Pandulf subdeacon and member of the papal household, Brother Aymeric master of the knighthood of the Temple in England. That makes a grand total of eleven.

The Barons and laymen mentioned at the beginning of Magna Carta: William Marshal earl of Pembroke, William earl of Salisbury, William earl of Warren, William earl of Arundel, Alan de Galloway constable of Scotland, Warin Fitz Gerald, Peter Fitz Herbert, Hubert de Burgh seneschal of Poitou, Hugh de Neville, Matthew Fitz Herbert, Thomas Basset, Alan Basset, Philip Daubeny, Robert de Roppeley, John Marshal, and John Fitz Hugh. That makes a grand total of sixteen.

Although the Barons had mounted the rebellion, the Church saw the possibility of stemming the process started by Henry II to restrict its power and influence in England.

On June 15th, 1215 John's seal was placed on the articles which became known as Magna Carta. John was confident that the pope would never support the provisions of Magna Carta because it severely challenged the feudal rights of the king. It gave the Barons the right to challenge the king and withhold allegiance if they disagreed. John had placed England under the protection of the pope so that the Church was actually the feudal power. John was correct. He wrote to Pope Innocent III who set aside Magna Carta saying that it had been extracted by force and it had been agreed to without his permission.

"Signing of Magna Charta by King John" published in Barclay's Dictionary, about 1850. Courtesy of Steve BartrickThe Barons saw this as a betrayal and justification for removing John. They offered the crown to the dauphin, Prince Louis of France, son of Philip II. By September John was moving through the country trying to regain territory. In February, 1216 he regained the territory in East Anglia, but the Barons held onto London and a small French fleet joined them there. A storm wrecked many of John's ships, weakening his defenses against France. He had to return to East Anglia to put down fresh revolts and then travel north to Scotland to attack Berwick to expel the Scots. Celebrating his victory there, he either ate too much and contracted dysentery, or he was poisoned by a monk. It really depends on which story you like, either way, he died.

Henry III

His son, Henry III, inherited the throne at the age of ten. William Marshal and Hubert de Burgh were appointed regents. The south was still held by the Barons and the French and it wasn't until 1219 that they were forced to leave. Within a month, Magna Carta had been reissued in his name, this time with the agreement of Pope Innocent III. It's interesting to note that an amended copy of Magna Carta was sent to Ireland in the name of Henry III by his regents. Presumably this was to ensure their loyalty and remove one threat so that energy could be targeted on regaining the English lands. Magna Carta was used in this way repeatedly through history.

For instance, in 1297 the Barons again rose in rebellion against Edward I who was increasing taxes on wool and forcing the Barons to grant aid to support campaigns in Flanders and Gascony. To quell the rebellion, Edward I reissued a revised Magna Carta. This one forbade the king from raising taxes without the consent of the country. It also, as did the first, established a council of advisors from among the Barons, but it was just as ineffectual. It was too early in the transition from feudalism to develop the customs and expectations of participatory government. (A translation of that charter is available from the US National Archives, see below).

Magna Carta Today

It was only through history that the rights implied by Magna Carta took on global significance. The reissues continued to deal with local problems, rather than seeking to establish sweeping principles. It was by accumulating individual rights that the common law began to be able to be used as a set of guidelines for the limitation of power and a definition of the basic rights of people. During the initial negotiations with King John, the language referred to the Barons, but in the final copy, the word "freemen" was used. This small change would impact the unique character of government under the English Kings.

Magna Carta was an important step in a number of ways. It established limits on the king's power. It didn't matter what limits, the idea that there were limits set the stage for the future. It strengthened the rights to private property. It strengthened the system of courts to enforce an equal law throughout the country. In this short description of the times, every time you turned around the kings were haring around fighting battles, besieging castles, and retaking and losing territory. It may seem to be romantic to put on armor and sit on your charger with a lance, but the reality was death by dysentery, gangrene, pneumonia, and starvation. When a castle was besieged, it was mostly a matter of waiting for the people inside to die of starvation. Women, children, and anyone else who had taken shelter at the time were part of the cost of the battle. In the meantime, the fields were not planted, the animals were slaughtered, and the buildings outside the castle destroyed. Even if the castle was rescued, the economy was destroyed and people left in poverty for years. Laws that could settle property disputes through the courts and could be applied even-handedly irrespective of who was in power at the time freed the Barons from internal threat. Later writers, such as Vattel, began to apply this concept across borders, but at the time the feudal system was learning to live with the people in the next castle.

Several clauses deal with debt and interest. For instance, when a minor inherited the debt of his or her father, interest could not be collected until the child reached maturity. At the time, only Jews could legally be moneylenders due to Church laws against usury; charging interest for a loan. There was a great anti-Semitic sentiment at the time, in part due to the extreme taxes levied which required many to borrow money. In fact, on their way to Runnymede, the Barons had ransacked Jewish homes. Archbishop Stephen Langton, who was present advising the king, but who had supported the Barons, later instituted a law requiring Jews to wear identifying badges in 1222, evocative of the practices in Nazi Germany. These clauses are not found in the version sent by Henry III to Ireland nor in subsequent versions.

It is difficult to say whether the clauses were primarily inspired by anti-Semitism or anti-Semitism was aggravated by anti-usury. It is certainly an attempt to regulate or mitigate the negative effects of lending and interest, especially on the helpless. Today, we still have problems with laws concerning lending and borrowing. The modern credit card has placed millions of people in debt leading to bankruptcy. To protect their profits, the credit card companies forced legislation to exclude them from the forgiveness of bankruptcy. Credit card debt and interest are perpetually compounding and the interest rate is not fixed. The economies of countries like Brazil and Mexico have crumbled under the weight of interest payments. In mediaeval England most debts were to the crown in the form of back taxes and tithes, a form of national debt. As of January 2006 the US national debt topped 8 trillion dollars. We don't feel the burden of this debt as immediately as did the Barons. They dealt with immediate rather than deferred payments.

The practice of paying scutage came from the recognition that when the knights and peasants went off to fight another battle, the community was left without workers and skilled craftsmen. The rule of law and the ability to settle disputes without weapons was slow to develop even within national boundaries. The idea of law applied equally and without the ability to force decisions based on position or power was essential. Trial by jury was just the method used. The expansion of law to cover those with no power, minor children and women, was about property at first, but was expanded over the centuries. Finally, the principle of taxation with consent begins to develop, and is more clearly delineated in the version of Magna Carta issued by Edward I. The tax caps of California and Massachusetts in the 1970's and 80's which spread to most other states are based on the principles established in the 12th century.

"Court of Common Pleas. " Engraved by J.C. Stadler after a picture by Thomas Rowlandson. Courtesy of Steve BartrickThat is not to say that Magna Carta invented tax caps. Although there are direct links between the articles of Magna Carta and our present systems, the similarities between then and now lie also in the fact that we are struggling with the same issues, and, sometimes, we have improved upon the solution. When the articles demand a limit on the size of the forests and the corruption of the warders, it is a clue to their sense of ethics, morals, and individual rights. They struggled with the issue of taxation just as we do today. The growth of the merchant class is attested by the number of "special interest" articles related to travel and trade. Issues of local versus central responsibility are reflected in the issue of who is to build the bridges. In the 12th century it would seem that locals were ordered to build bridges, and wanted to shift the responsibility to larger entities. It makes sense to us today that the central government would build the Golden Quadrilateral in India, but we're still not sure who should be responsible for building a bridge to an uninhabited island in Alaska.

Magna Carta certainly was used as legal precedent in later times, sometimes with little justification. Few people have read it, just as few people have read the Declaration of Independence or the complete US Constitution. Yet, magical properties are attributed to Magna Carta. "It is the beginning of democracy, the jury system, and the world as we know it." This is hyperbole. What Magna Carta is, is a document that reflects the problems of that era and at the same time reflects a changing ethic toward liberty, individual rights, and the growing knowledge that something more than custom must bind the culture together. It is the idea of Magna Carta that inspires us, not the reality.

It is the foundation upon which later writers explored, more consciously, the nature of government, society, and human life itself. Grotius, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Vattel, Jefferson, Paine, and hundreds of others built upon the foundation and attempted to advance it. It unleashed and legitimized challenges to power and force, but through law and principles of human rights. We are still working toward achieving the Universal Declaration of Human Rights passed by the United Nations in 1948. That, like Magna Carta and the US Constitution, achieves reality on a case by case basis, growing with the times and struggling to achieve principles to advance humanity.

There are four copies of Magna Carta from 1215. Originally there had been at least thirteen. It didn't seem very important at the time, and the few that survived did so by neglect rather than design. It came to be called Magna Carta to distinguish it from a another charter dealing with the Royal Forests, not because it was considered important. If anything, Magna Carta was seen as an evolving document, reissued when necessary to calm rebellion or answer specific demands. In was reissued three times while Henry III was a child and then again in 1237 when he was an adult.

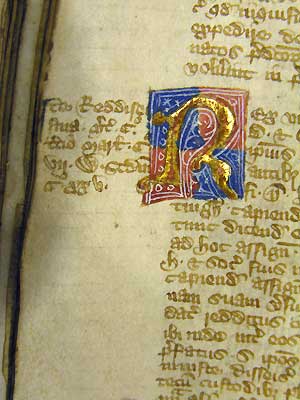

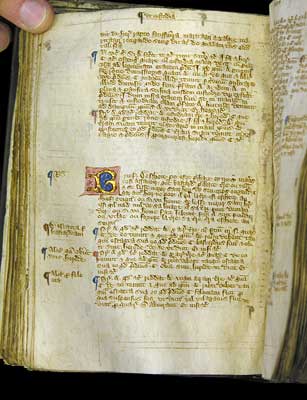

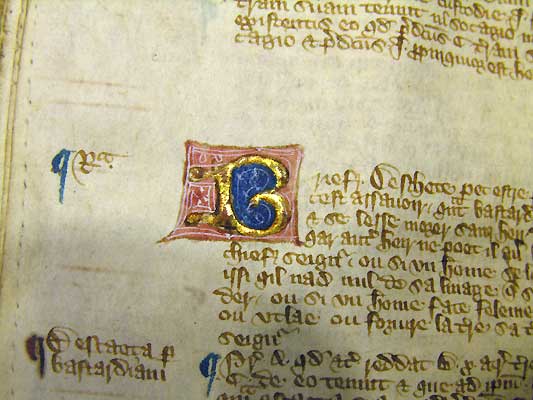

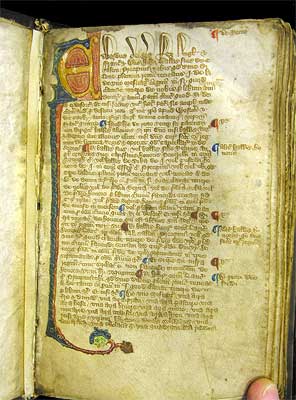

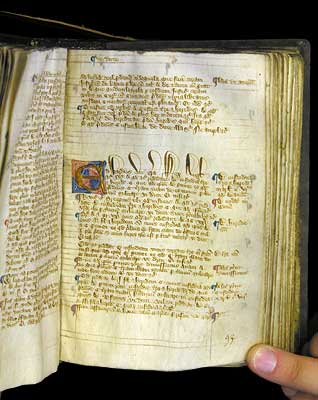

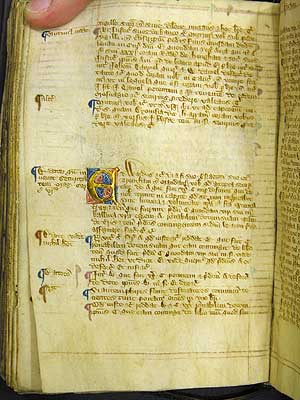

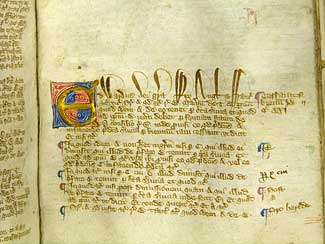

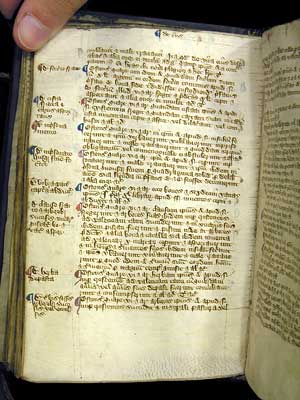

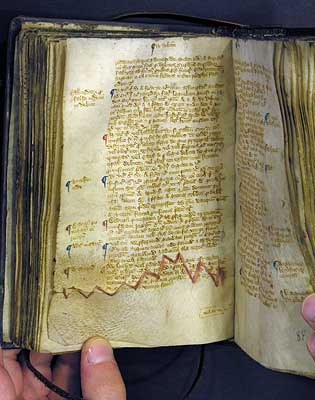

Scriptorium Monk at Work, from Lacroix, 1891. Courtesy Liam Quin's Pictures From Old Books Web site.The copy of Magna Carta shown below was hand written on parchment in 1350. It's in Latin and illuminated and colored. The calligraphy shows little fading. Below you will find both whole pages and close-ups of illuminated letters. If you click on an image it will take you to a larger version. In Firefox and IE, the larger image will be sized to fit your screen. If you then click again, you will see it full size and in greater detail. The images may be downloaded and used for educational, non-commercial purposes. Please link to this page for copyright information.

Further Resources:Magna Carta

The text of Magna Carta, photographs of original from 1215 -- click on the viewer for excellent close-ups-- from the British Library

English translation of 1215 Magna Carta with explanatory notes to the side -- from the British Library

The text of Magna Charta Hiberniae granted by Henry III, on 12 November 1216, with some changes applicable to Ireland. The Charter of 1216 was a re-issue with modifications, confirmed by his infant son as a royal concession and sealed with the seals of the Papal Legate and William the Marshall, the Regent.

The text of the 1297 version of Magna Carta with photographs -- link provided for English Translation -- US National Archives

The plain text of Magna Carta from Constitution.org

Background and People:

The Family Tree for Monarchs of England from Tina Cooper -- it's relatively easy to follow for our period. Not all of the actors are included -- Geoffrey's children are not shown and many of the women who married out of the family are excluded to make things easier to read.

The text of Edward Grim's account of the murder of Thomas à Becket, from Medieval Soucebook, translated by Dawn Marie HayesPhilip II of France (King from 1180 - 1223) -- Richard I's companion on the Crusade and John's nemesis -- from Infoplease

Text of Assize of Clarendon The formal beginning of trial by jury in legislation. The application of civil law to members of the clergy was a major step in the separation of church and state. From Medieval Sourcebook

Our Precious Jury System: It's Passed the Test of Time, By James W. Gilchrist, Jr. South Carolina Trial Lawyers Bulletin, Winter 1989

"On assessing the role of Gilds in the development of religious drama in the later Middle Ages", by David Debono

The English Royal Forest and the Tale of Gamelyn by Leslie Campbell Rampey -- background on the laws and regulations concerning the forests and the resentment of the populace.

"Magna Carta: A Commentary on the Great Charter of King John, with and Historical Introduction" by William Sharp McKechnie (Glasgow: Maclehose, 1914). Discusses each article of Magna Carta and related social history.

Calligraphy:

The Book Arts Listserv -- searchable -- discussion of topics like vellum, parchment, binding -- from Stanford University

Basic difference between parchment and vellum -- from Hilary Gowen

Parchment -- describes the process to make it -- from Octavia Randolph

Analysis and Review of Parchment -- recipes for parchment -- delightful site from Nicholas Yeager

For parchment prepared according to mediaeval recipes -- from Inden witten Hasewint

For the scientific approach: "The Effects of Relative Humidity on Some Physical Properties of Modern Vellum: Implications for the Optimum Relative Humidity for the Display and Storage of Parchment." Eric F. Hansen, Steve N. Lee, and Harry Sobel. from The American Institute for Conservation

Calligraphy, illumination, and guilding from Traditional Book Arts

Examples of mediaeval calligraphy throughout Europe. On the home page, click on 'Thaxted' under Styles. From Wlodek Fenrych

Robin Hood:

The Robin Hood Project -- critical essays, photos and some fun stuff too -- from The University of RochesterRobin Hood: The Early Poems -- from Thomas Olgren, Purdue University

Hereward the Wake -- Yet another contender for the legendary Robin Hood. Every robber, highwayman, or person who ran afoul of the law with a name starting with "H" seems to be a possible Robin Hood. As you read through though, you learn a lot of social history.

(c) Marilyn Shea, 2006