Montaigne's Challenge:

To Dare to Say All That One Dares to Do

Gretchen Legler

The following is based on the lecture and notes of Gretchen Legler.

Lopate, Mairs, Harrison, Slater—These are some of the personal essayists of our time, baring their souls, revealing for you their most intimate secrets, desires, fears, confessing themselves—daring to write all that they dare to think or do.

Who cares? Well, we all care, because as much as this intimate

discourse might make us squirm, we want to see ourselves, don’t we? We

hunger for meaning, we thirst for details of other peoples lives,

gratefully, so we can hope to find ourselves—so we can say, yes, life is

like that, that’s how it is, that’s the way it feels.

Who cares? Well, we all care, because as much as this intimate

discourse might make us squirm, we want to see ourselves, don’t we? We

hunger for meaning, we thirst for details of other peoples lives,

gratefully, so we can hope to find ourselves—so we can say, yes, life is

like that, that’s how it is, that’s the way it feels.

Has it gone too far? Well, some will always say "yes". That our hunger for honesty and truth telling has become mere confessionalism, narcissism, exhibitionism, sensationalism. We have live web cams in people's bedrooms and bathrooms. We have multiple reality TV shows, including Survivor. Today we are in the midst of a babble of voices, maybe even a roar, of people who are writing about their lives, revealing things we’d rather not think about—their armpits and bowel movements, their incest stories, their sexual desires, their lives in faraway lands, their coming of age stories, their families—coming in from the margins where they’ve been silently waiting. It’s as if the personal essay and the memoir today are taking the pulse of the culture at large, not just a little slice of it—the rich, the famous, the educated, the important.

What is it with all this soul barring—this lack of artifice. It’s so real it can get ugly, can’t it? And it can be disturbing.

My seventy-five year old, mother, for example, is disturbed by even the

relatively conservative personal revelations I share in my own nonfiction:

“I think you should stick to journalism," she said. "Why would anyone want

to write about THAT?”

My seventy-five year old, mother, for example, is disturbed by even the

relatively conservative personal revelations I share in my own nonfiction:

“I think you should stick to journalism," she said. "Why would anyone want

to write about THAT?”

How did we get here to this place in the early 21st century, where it seems that everyone has a personal, intimate, revealing, sensational, scandalous, poignant, important story to tell, and is telling it? Some say it all started with St. Augustine, the fourth century Catholic bishop who wrote The Confessions, what some regard as the first real autobiography. In it he writes of his youthful transgressions, his theft of fruit from a neighbor's orchard, his lusts and his intemperance. His goal was spiritual growth—to know himself as a way of getting closer to God.

Others, however, say it all started with our man here—Michel de Montaigne—a French nobleman of the 16th century who is regarded by many as the inventor of the personal essay— a philosopher, politician and writer who some say is the greatest essayist who ever lived.

Montaigne lived a long time ago—four and a half centuries ago. Yet, his influence on the personal essay and the memoir—on personal writing—follows us right up through the early and English essayists of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries—Addison & Steele, Samual Johnson, Hazlitt, Lamb, Orwell and Woolf, until today. Montaigne never said this, but I believe he could have: "The personal is political." It became the mantra of the 70’s feminist movement—what you do in your personal life—in private—has repercussions in the larger social and economic world.

Montaigne is political. Why? He chose to write, for one

thing, not in Latin or in the formal French of his time, but in regular

language. There is a democracy in this. And he chose to attempt

what no one before him, he claimed, had attempted—truly honest and intimate

explorations of the self—with no masks. We know ourselves so little,

Montaigne felt. We pretend so much. His enemies were ceremony

and convention.

Montaigne is political. Why? He chose to write, for one

thing, not in Latin or in the formal French of his time, but in regular

language. There is a democracy in this. And he chose to attempt

what no one before him, he claimed, had attempted—truly honest and intimate

explorations of the self—with no masks. We know ourselves so little,

Montaigne felt. We pretend so much. His enemies were ceremony

and convention.

One of the fundamental principles woven throughout the essays is a belief in our humanity. We are all human. We are all average human beings. Although a French nobleman, he farted when he ate beans, he loved sauce, he scratched his ears, prefers glasses to metal cups…and he made fun of himself.

In his writings about education, he stressed that we should know that position and wealth does not make us different from anyone else. We still have the same frailties and weakness of others. He wanted men to strive to know themselves and to live well.

Many words are used to describe Montaigne: common sense; down to earth

view of human nature; humorous; skeptical; irreverent; aware of human

limitations. He created four and a half centuries ago a flexible,

informal, highly personal, introspective and free roaming kind of writing

whose goal and purpose was to explore the continent of the human—roaming

over multitudes of subjects from loyalty to friendship to education to sleep

to smells and even cannibals. His motto was not “This I know,”

but—“What do I know.” Que scais-je?

Many words are used to describe Montaigne: common sense; down to earth

view of human nature; humorous; skeptical; irreverent; aware of human

limitations. He created four and a half centuries ago a flexible,

informal, highly personal, introspective and free roaming kind of writing

whose goal and purpose was to explore the continent of the human—roaming

over multitudes of subjects from loyalty to friendship to education to sleep

to smells and even cannibals. His motto was not “This I know,”

but—“What do I know.” Que scais-je?

He was born in Bordeaux France in 1533, at the beginning of the Renaissance,

to a very rich family. Educated formally in Latin, he studied law, became a

lawyer and member of the Bordeaux parliament. He ran in the high crowds with

kings and queens—and even served as a sort of ambassador during wars and

arguments between Catholic and Protestant forces in the later part of the

century. He was also a philosopher (a skeptic and humanist) and a

writer. I will be talking about him mostly as a writer.

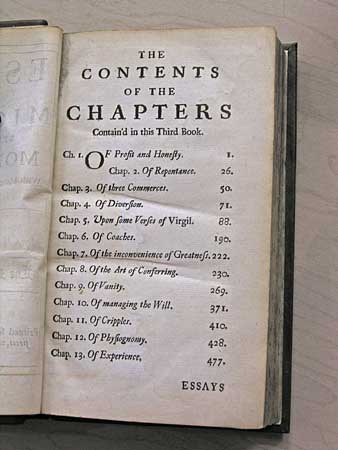

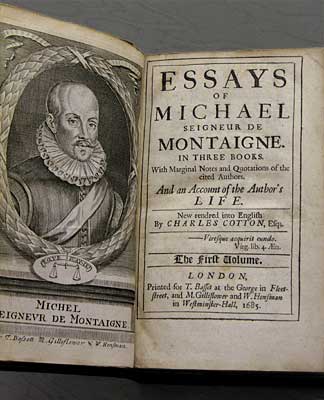

He began his essays in about 1570 and by his death in 1592 had written three volumes. They were first published in 1580. The editions that we have here for you to look at were translated into English by Charles Cotton and were printed in 1685.

The Renaissance of the 16th century found Europe in the midst of a cultural movement that brought a period of revolution in science, art, philosophy, religious thinking. The 16th century is regarded as the transition between the middle ages and the modern era—a period of rebirth in learning and knowledge. Other Renaissance figures who may or may not have been contemporaries of Montaigne: Writers: Shakespeare, Christopher Marlow, John Milton, Rabelais, Miguel Cervantes, John Donne. Painters: Botticelli, Brunelleschi, Dürer, Michelangelo, Raphael, da Vinci. Science: Copernicus (1543—his idea that earth is not center of universe), Galileo, Kepler. Philosophers/Religious leaders: Machiavelli, Martin Luther.

This is the time when explorations were being undertaken all over the

world, as ships sailed out from Europe, fueled by a new wealth of a growing

merchant class in Europe, in search of money and goods. At the beginning of

the century Cortez was off to mess around in South American with other

conquistadores. Columbus was “discovering” the New World, Magellan was

sailing around out there. Montaigne was part of this milieu. Humanism

was in the air. And the doors were opening to freer, more speculative

and more open ways of thinking.

This is the time when explorations were being undertaken all over the

world, as ships sailed out from Europe, fueled by a new wealth of a growing

merchant class in Europe, in search of money and goods. At the beginning of

the century Cortez was off to mess around in South American with other

conquistadores. Columbus was “discovering” the New World, Magellan was

sailing around out there. Montaigne was part of this milieu. Humanism

was in the air. And the doors were opening to freer, more speculative

and more open ways of thinking.

Montaigne has a license, as it were, to write about the body, about pleasure, about the individual mind. He too was sailing off, in a way, into another country. He delved into an enormous range of topics from vanity to Virgil, from cripples to coaches and from truth to cannibals. He was exploratory, undogmatic, and curious about other cultures that he was learning about though explorations (e.g. of Cannibals).

He was a revolutionary in more than one way—it wasn't just subject matter—the writing about the personal life—it was also in form. For one, he wanted to write these essays in a form of writing that would be free of the formal and elaborate structures that were common in scholarly works of the time. He wanted to write on a variety of subjects. He wanted to explore his own thoughts and explore human beings. He wanted to put his ideas in a tentative form—not pretend they were absolute truth. Scholars say his favorite terms were "Perhaps," "Maybe," "I think," "It could be." rather than "You should," "It is true that," etc.

He devised a term for his writing: essay—from the French essayuer, to try or attempt, to make an effort, to set out on a journey. The root meaning of the word is to travel, to try things out, to explore, to journey. Montaigne's essay is an excursion—a kind of mental journeying that takes the writer and the reader into new country.

He had deep convictions about the instability of things, the diversity of

humankind, and flux in the world.

He even felt that the human form itself—the self—was a mutable thing that

one could write into existence—one created the self, in a sense, by writing

about it.

He had a freewheeling sense of exploration that pushed boundaries of content and style—reaching into the dark places of human experience. Such an attitude flew in the face of the medieval scholastic, smug in his intellectual arrogance, who believed that, armed with the Scriptures and the masters of theology, he possessed the sum total of necessary knowledge (salvation).

We can see the hallmarks of today's personal essay in much of Montaigne's work.

Intimacy: “I dare to write all that I dare to think.”

Self revelation. Personal details. A confidential manner. Candor. Self disclosure. “We must remove the mask,” he wrote. A certain kind of nakedness. “How the world comes at another person—the irritations, the jubilations, aches, pains and humorous flashes….” This is the stuff of the personal essay.

Montaigne had the idea that there is a certain unity to human experience: “In every one of us is the entire human condition.” When a writer is telling about herself, she is telling, to some degree, about all of us.

Honesty: “The struggle for honest is central to the ethos of the personal essay.” “The impulse of the essayist to scrape away illusions”

Humility: What do I know? Idea of “true intellectual humility.”

Humility: What do I know? Idea of “true intellectual humility.”

Of all his practices, some say, was his propensity, to follow his

thoughts no matter where they led him. This created a spontaneity of

mental discovery and a challenge to formal structures. He wanted to

know what he really thought, not what he was supposed to think. His

conviction that we should look to ourselves and know ourselves in order to

write about ourselves, others and the world around us, has been a powerful

model for other writers, including me—I’ve come to him, in many ways,

through Virginia Wolf, but that, is another lecture….

Following the presentation the audience was invited to examine the three volumes of essays.

|

|

Montaigne

portraits from

Wikipedia and

University of Texas collection

|