What is an American? Crevecoeur, Tocqueville, and the

Ideology of American Exceptionalism

Allen Berger

The following is the outline of his lecture written by Allen Berger:

1. Why Crevecoeur and Tocqueville: Explanation and

Confession

a. Concerns about health of American democracy: some ideas of Crevecoeur and Tocqueville can be instructive

b. No expertise in either author (not a historian, political scientist, or expert in American Studies)—background as cultural anthropologist

c. Instead I come to the topic primarily as an educator

i. Started career teaching at a small Catholic college—Core program—Crevecoeur and Tocqueville included in common first-year, general education curriculum that aspired to create community-wide discourse about: a) factors shaping individual lives and life chances in America, and b) the nature of American society

ii. Longstanding belief in need for college education to prepare students for citizenship and leadership in a democratic society (liberal education)

iii. Concerned that while we continue to give lip service to this idea, the reality is that our commitment to education for citizenship has been seriously undermined by two related trends-

1. Barry Schwartz (Swarthmore)—economic imperialism—def.: the spread of economic considerations to previously non-economic aspects of life (perceptions of value and purpose of college)

2. Culture of individualism and consumer choice: student choice and faculty choice in a “Chinese menu” distributive curriculum that values breadth in education but at the same time sacrifices commonality and community

iv. My interest in moral education and in education for citizenship undoubtedly makes me seem very old fashioned; conservative even—certainly countercultural (evidence from recent Diversity Digest study--handout)

v. Brian Bex and I: we differ in our politics, but we ask identical questions:

1. If a college education is effectively to prepare students for citizenship and for leadership, are there certain issues and ideas that we ought to aspire to engage seriously together across the academy as a true community of learners?

2. Should there be a common core that doesn’t eliminate all choice in general education, but complements and balances it?

3. And if so, what common readings belong in such a Core?

vi. No proposal tonight for a grand curricular design (and not a CAO’s role)--but suggest that Crevecoeur and Tocqueville aren’t bad places to start, at least for students who will be the next generation of citizens in this country (my own experiences at U of C).

2. So who are these guys?

a. Both Frenchmen; both visitors to America, one in the colonial period, in the years leading up to the revolution, the other in the early decades of the American Republic

b. Both wrote about America: comparisons to old world of Europe (particularly France) and with a fascination for what made America different or exceptional

c. Basic biographical facts:

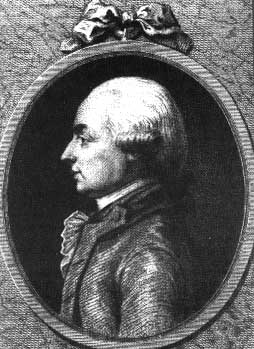

i. J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur

1. born in Normandy in 1731

2. finished education in England; embarked for America in 1754

3. worked as a surveyor, peddler, Indian trader; traveled throughout the colonies and beyond into the wilderness of the interior

4. settled in Orange County, NY, married into fairly prominent British family, became something of a gentleman farmer on “Pine Hill,” a 120 acre farm

5. started a manuscript on American society and agrarian life

6. Tory, but distrusted by British

7. 1780-returned to England, later France, publishing in both countries “Letters from an American Farmer,” which was enormously influential in Europe

8. returned to New York in 1783, served as French consul; Pine Hill had been burned in an Indian raid, his wife was dead, and his three children were gone (although he later tracked them down)

9. associated with many leading figures of the early American scene, including Benjamin Franklin whom he had befriended in Paris

10. returned to France in 1790; died in 1813

ii. Alexis

de Tocqueville (Comte Alexis-Henri-Charles-Maurice Clérel de Tocqueville)

ii. Alexis

de Tocqueville (Comte Alexis-Henri-Charles-Maurice Clérel de Tocqueville)

1. born in Paris in 1805

2. aristocratic background; studied law and served as a magistrate

3. traveled to America in 1831 w. another young magistrate, Gustave de Beaumont, landing in Newport, RI, a month before turning 26

4. traveled here ostensibly for purpose of studying American penal system; T. later labeled this a “pretext”; said the real purpose was to see firsthand “what a great republic is”

5. spent nine months in America, visiting both cities and the frontier; met ordinary Americans, road in stage coaches and steam boats, met leaders of the day (such as John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Andrew Jackson), and read broadly

6. eventual result—Democracy in America, published in France in 1835

7. some scholars judge it the best book on democracy and the best book on America every written; certainly it may be the most often quoted

8. later in life served as a public official, including as a representative to the Chamber of Deputies and minister of foreign affairs

9. died in 1859

3. Why is Crevecoeur and in particular Letters from an American Farmer worthy of our attention or our students’ attention?

a. perhaps the first author to ask the question: “What is an American?” (certainly still a relevant question) His work is part autobiographical memoir, part philosophical travel book, and part formal essays—all framed as a series of letters from an American farmer, James, to a correspondent in England who is curious about the manner of life in the American colonies

b. it is a work that defined America to Europeans (along w. Franklin)

c. Not great literature or ethnography or social theory, but introduces ideas and visions of America that have shaped both our ideas and myths about ourselves and also how others have perceived us; Crevecoeur portrayed American society as different from any that had previously existed; he described what he considered revolutionary principles of social and economic organization and a distinctive, non-European consciousness or ethos that emerged as a result.

d. READINGS FROM LETTER 3: “What is an American?”

e. In just these short excerpts, a rich number of themes and ideas:

i.

America as a melting pot: what melts is memory—memory (of old world and old

identities.

i.

America as a melting pot: what melts is memory—memory (of old world and old

identities.

ii. “American Adam”—a special or unique breed of human who is less parochial, more open-minded, and more engaged civicly (Emerson --America offered “new lands, new men, new thoughts.”)

iii. Identification of individualistic, egalitarian, anti-statist, and laissez faire values as the core of American national identity (Lipset: in Europe “nationality is related to community, and thus one cannot become un-English or un-Swedish. Being an American, however, is an ideological commitment. It is not a matter of birth. Those who reject American values are un-American.” Teddy Roosevelt-- America is a “question of principle, of idealism, of character, not a matter of birthplace, of creed, or line of descent.” To think of Americans, as Benjamin Barber has written, “as a special people capable of realizing a special destiny” takes hubris, but perhaps the greatest purveyor of this idea in the eighteenth century was a Frenchman, not an American.

iv. Lack of class consciousness in America (later generations of historians folded this into the notion of American exceptionalism—no tradition of working class radicalism, no significant socialist movement or labor party)

v. Optimism, grounded in materialism and environmental determinism—where people live, the material conditions of their lives, what they do, and how they work determines how they think, indeed who they are. The European transplanted to America can literally become a “new man.” (Crevecoeur’s use of the masculine)

vi. The American dream

f.  CONCLUSION:

Whether or not one agrees with these ideas, it is hard to deny that they have

had a strong impact on American culture; they are an important part of a

national story that we tell about ourselves. Having students read passages

from Crevecoeur is therefore a wonderful launching pad for conversations about

the nature of America and American myth. Of course, there are competing visions

and competing stories, stories of hyphenated Americans, of multicultural

identity, of diversity, of disadvantage, of imperialism rather than innocence.

But isn’t that the point? Our stories define for us who we are. And

our students need to understand these stories, their origins, their limitations,

what they show and what they hide, whose interests they serve, and how they

function in the context of a society that has changed dramatically since the

time of Crevecoeur. And, I would argue, perhaps no future citizen needs

this education more than a citizen who aspires to be a future teacher (of which

we have many at UMF). If there’s one thing Crevecoeur makes clear it is

this: the ideology of American exceptionalism not so much an example of 20th

century superpower arrogance or 19th century imperialist

revisionism/hypocrisy; it is our original story and it is a story whose repeated

telling has wielded enormous influence.

CONCLUSION:

Whether or not one agrees with these ideas, it is hard to deny that they have

had a strong impact on American culture; they are an important part of a

national story that we tell about ourselves. Having students read passages

from Crevecoeur is therefore a wonderful launching pad for conversations about

the nature of America and American myth. Of course, there are competing visions

and competing stories, stories of hyphenated Americans, of multicultural

identity, of diversity, of disadvantage, of imperialism rather than innocence.

But isn’t that the point? Our stories define for us who we are. And

our students need to understand these stories, their origins, their limitations,

what they show and what they hide, whose interests they serve, and how they

function in the context of a society that has changed dramatically since the

time of Crevecoeur. And, I would argue, perhaps no future citizen needs

this education more than a citizen who aspires to be a future teacher (of which

we have many at UMF). If there’s one thing Crevecoeur makes clear it is

this: the ideology of American exceptionalism not so much an example of 20th

century superpower arrogance or 19th century imperialist

revisionism/hypocrisy; it is our original story and it is a story whose repeated

telling has wielded enormous influence.

4. Why is Tocqueville and Democracy in America worthy of our attention as college educators interested in preparing future citizens? Answer: Tocqueville “is the best friend that democracy has ever had, and also democracy’s most candid critic.” Limitations of my discussion; Matt McCourt’s follow-up lecture. Focus tonight:

a. Tocqueville as an apostle of civic engagement

b. Tocqueville as a critic of Americans’ addiction to material well-being

c. Tocqueville as a skeptic of majority rule

d. Tocqueville as an appreciative analyst of a print-based culture

Civic Engagement

Perhaps more

than anything else, Tocqueville was impressed with Americans’ propensity for

participation in civic associations. He wrote: “Americans of all ages, all

stations in life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations.

There are not only commercial and industrial associations in which all take

part, but others of a thousand different types—religious, moral, serious,

futile, very general and very limited, immensely large and very minute… Nothing,

in my view, deserves more attention than the intellectual and moral associations

in America.”

In Tocqueville’s mind, this propensity was the basis of democracy—

It encouraged the development of social trust

It broadened people’s sense self, creating more enlightened participants in the policy capable of thinking in terms of the common good and mutual self-interest

It facilitated coordination and cooperation for collective benefit

It developed political and organizational skills

It resulted in an active citizenry that was not excessively dependent upon government

Since

Tocqueville, many political scientists have studied this aspect of American

society and have tried to specify the mechanisms by which civic engagement

and social connectedness lead to a healthier democracy

Since

Tocqueville, many political scientists have studied this aspect of American

society and have tried to specify the mechanisms by which civic engagement

and social connectedness lead to a healthier democracy

Banfield on southern Italy: The Moral Basis of a Backward Society: problem of amoral familism

Recent trend in political science to despair the disappearance of voluntary associations and the decline of civic engagement in America

Putnam: “Bowling Alone”

Putnam: “The rise of solo bowling threatens the livelihood of bowling-lane proprietors because those who bowl as members of leagues consume three times as much beer and pizza as solo bowlers, and the money in bowling is in the beer and pizza, not the balls and shoes. The broader social significance, however, lies in the social interaction and even occasionally civic conversations over beer and pizza that solo bowlers forego.”

Not just bowling: declining participation in PTA’s; disappearance of labor unions; shrinkage of fraternal organizations (Lions, Elks, Jaycees, Masons, etc.); fewer volunteers to be Boy Scout troop leaders; even declining socialization with neighbors

Common framework for understanding this phenomenon: decline in SOCIAL CAPITAL

(community resources that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit)

Questions:

Is it really happening?

Does it really have a dire impact on democracy?

Are new kinds of networks and organizations—e.g., those formed through electronic media—capable of making up for this loss?

Why is it occurring?

Geographic mobility

Women’s entry into the workforce

Affluence (e.g., vacations vs. holidays)

Technological transformation of leisure: television, VCR’s and DVD’s, computers

Material Well-Being

United States as most affluent society in the history of the world

Not an unmixed blessing: (recent Howe lecture)

Tocqueville for a different set of reasons thought the bourgeois addiction to material well-being, which he found particularly strong in America, was problematic (in particular, dangerous to democracy)

Tocqueville: “It is a strange thing to see with sort of feverish ardor Americans pursue well-being and how they show themselves constantly tormented by a vague fear of not having chosen the shortest route that can lead to it.”

Tocqueville had two fears:

1) the desire for material well-being, when it degenerates into materialism, is self-defeating: it leads to continuous cravings, escalation of needs, and paradoxically a reduction in levels of satisfaction

2) more importantly, it weakens social bonds and increases selfishness, and therefore is a threat to community and to democracy

Tocqueville advocated “self interest well understood”—as antidote to dangers of materialism—encompasses more than the self. Similarly, he spoke of a “sort of refined and intelligent egoism,” which he said was “the pivot on which the whole machine turns.”

Tocqueville: religion particularly important in producing this enlightened self-interest: “The main business of religion is to purify, control, and restrain that excessive and exclusive taste for well-being.”

Religion + civic engagement: produced a “second language” that united individuals, created communities and acted as counter-weight to the language of individualism.

“Habits of the heart.” vs. acquisitive individualism; virtue vs. materialism

Majority Rule

Tocqueville as America’s greatest fan, but also wrote: “I do not know of any country where, in general, less independence of mind and genuine freedom of discussion reign than in America.”

Tocqueville particularly skeptical of the

tyranny of the majority: “In America, the majority draws a formidable circle

around thought. Inside those limits, the writer is free; but unhappiness awaits

him if he dares to leave them. It is not that he has to fear an auto-da-fe, but

he is the butt of moritifications of all kinds of persecutions every day.”

Irony: even though Americans value individualism above almost all else, we do not place particular value on individuation of thought. In fact, we punish free-thinkers. (in some ways we punish thinkers period)

Rich body of sociological and political literature in the wake of Tocqueville that has examined the supposed anti-intellectual strains in American society.

Print-based culture

I have saved this part of Tocqueville’s observations for last, because it so closely relates to why we’re all here tonight: Brian Bex has lent us these first editions of great books, because he believes there is value in the printed word. There is not a faculty member at UMF who would disagree. In fact, what is college about if it is not about reading and discussing what one has read?

However, in this day and age, most college students arrive in the academy without having developed a habit of reading. Many even report that they don’t enjoy reading.

Tocqueville, on the other hand, was struck by the extent to which America was a nation of readers. He took particular note of the proliferation of newspapers, pamphlets, and broadsides.

Of course, for us it’s difficult to imagine a world without radios, without television, without computers, without movies, without telephones, without even photography. Printed matter was all that was available. And rates of literacy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century were higher in America than anywhere else in the world. Political discourse in our early democracy was written discourse.

In addition to penny newspapers, two other institutions grew at a phenomenal pace—libraries and lecture halls. Alfred Bunn: “Practically every village has its lecture hall… It is a matter of wonderment to witness the youthful workmen, the overtired artisan, the worn-out factory girl rushing after the toil of the day is over, into the hot atmosphere of a crowded lecture room.”

Lectures as “the oral equivalent of print”—w. linear, analytical structure of expository prose. The business of politics was conducted entirely through print and through lectures.

Try to imagine how different that is from the world in which we live today, where the business of politics is conducted primarily through 30 or 60 second television commercials. Where even the so-called debates that our presidential candidates have are little more than scripted exercises and opportunities for creating impressions rather than advancing cogent arguments, chances for honing a message, which of course means shrinking it down to bite-sized one liners that don’t even require a command of syntax.

What

is the impact on our democracy? On the quality of our decisions as

voters? On the kinds of candidates we elect?

What

is the impact on our democracy? On the quality of our decisions as

voters? On the kinds of candidates we elect?

Most Americans today agree that Abraham Lincoln was our greatest president. He was also, of course, a great orator. But he was gangly, awkward, many would say ugly, and he had a homely wife who was mentally ill. Could his candidacy have survived in the age of television?

If not, and I gather you agree not, then here’s the more important question (Postman): if our democracy arose in a print culture where public discourse was characterized by the coherent, linear, orderly arrangement of facts and ideas, can it survive in a video, electronic culture characterized by sound-bites, multi-tasking, short attention spans, and flashy visuals?

These are the kinds of questions that reading Tocqueville forces us to ask?

And, to return to where I started, if you agree with me that these questions are of utmost importance if we are to preserve our democracy, then shouldn’t every college student be reading Tocqueville and perhaps Crevecoeur too?