Mary Wollstonecraft: An 18th century thinker with revolutionary

ideas for the 21st

Denise DeVito

The following is a paper written by Denise DeVito:

Mary Wollstonecraft:

A blueprint for human change

"I am going to be the first of a new genius the peculiar bent of my nature pushes me on." Mary Wollstonecraft wrote to her sister Everina, early in her career. Wollstonecraft worked hard at "being the first of a new genius." She wrote and urges her sister not to speak of her goal. "My undertaking would subject me to ridicule - and an inundation of friendly advice, to which I cannot listen – I must be independent."

Violence and poverty surrounded Wollstonecraft's early life and predisposed her to rebel social wrongs. Her father's preference for drinking and idleness left the family penniless and often nomadic. Her mother's depression left the family emotionally vacant. Mary's six siblings and her parents relied upon her for economic support throughout their lives.

Wollstonecraft's career encompassed being a widow's companion, a governess, a writer for Johnson's

Analytical Review, and author of several books over the span of her 38 years. Her experiences with the upper classes coupled with the violence of her formative years led Wollstonecraft to a personal resolve in self-education and self-possession.

Wollstonecraft's career encompassed being a widow's companion, a governess, a writer for Johnson's

Analytical Review, and author of several books over the span of her 38 years. Her experiences with the upper classes coupled with the violence of her formative years led Wollstonecraft to a personal resolve in self-education and self-possession.

She read voraciously. Her habits were suspicious to the upper class women in which she worked and observed. Rather than chat about current fashion or make up, Wollstonecraft preferred privacy and her books. Societally, reading alone was seen as selfish and antisocial, a sign of self-indulgence that bordered on moral danger of excess.

Wollstonecraft as a person was famous, then notorious. Her life has held such a fascination over the centuries that more biographies have been written about Wollstonecraft than any other figure.

There were those who wished to deprecate Wollstonecraft. Henry Fuseli said she was a ‘philosophical sloven.' Horace Walpole referred to Wollstonecraft as ‘a hyena in petticoats.' John Adams called her ‘a mad woman.' The New York Times Literary Supplement stated she was ‘little short of monstrous' at the turn of the 21st century. Of her work, Benjamin Silliman, urged that her words be kept secret lest they promote in women the idea of independence from man. Thomas Taylor suggested ‘elephants should satisfy women as lovers,' and that dogs breeding could illustrate to children the facts of life in reference to Wollstonecraft's views on equal and truthful education for both sexes.

People have rarely been neutral about Mary Wollstonecraft. Some have gone to great lengths to ridicule her ideas about equality while others take courage in her words and measure the mental engagement with the prominent minds of the day. William Blake, Robert Southey, William Godwin, George Eliot, Mary Hays, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, heralded her work and insight.

When

Vindication on the Rights of Woman first appeared, it was well received; seen as the latest treatise on female education.

Vindication appeared in 1792 arriving against the backdrop of a social and intellectual revolution. There had been an uprising in the American colonies leading to their independence; a revolution was exploding in France; controversial attitudes were swirling in England. A cry for equality for all social classes was being heard. Included among these conversations were pleas regarding women's education.

When

Vindication on the Rights of Woman first appeared, it was well received; seen as the latest treatise on female education.

Vindication appeared in 1792 arriving against the backdrop of a social and intellectual revolution. There had been an uprising in the American colonies leading to their independence; a revolution was exploding in France; controversial attitudes were swirling in England. A cry for equality for all social classes was being heard. Included among these conversations were pleas regarding women's education.

Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman was the first for women's transformation to enter mainstream British and American politics. Certainly there had been others who had argued politically for women's rights- Christine de Pisan, Mary Astell, Lady Wortley Montague, Catherine Macaulay – but Wollstonecraft's words were the first to enter mainstream conversation regardless of social class.

Many during this time viewed human nature as unchangeable, revolutionaries were arguing that political institutions made men and women what they are. Wollstonecraft was one who believed that if institutions were changed, then human nature would change. Wollstonecraft desired to bridge the gap between mankind's present circumstances and ultimate perfection. She was truly a child of the French Revolution and saw a new age of reason and benevolence close at hand. In her earlier book, A Vindication of the Rights of Man Wollstonecraft presented her vision of a society, based upon equality of opportunity, in which talent—not the wrongful privileges of gentility—would be the requisite for success.

In Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft applied principles of liberty and equality to sexual politics. Vindication is a devastating critique of the 'false system of education' which she argues forced middle-class women to live within a stifling ideal of femininity: 'Taught from infancy that beauty is women's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and roaming round its gilt cage seeks only to adore its prison'. Wollstonecraft addressed women as 'rational creatures', urging them to aspire to a wider human ideal which combines feeling with reason and the right to independence. Wollstonecraft dedicated Vindication to the French politician Talleyrand in glib condensation. Talleyrand had just drawn a report on the national need for an education that educated both males and females. He had asserted girls were inferior by nature, echoing the thought of the day. Wollstonecraft countered that femininity is not the creation of nature, "it is the enfeebled consequence of miseducation.'

The topic of women's education had been ongoing for approximately a century, so the publication of Wollstonecraft's Vindication brought respect rather than criticism. Most of what Wollstonecraft wrote was categorized under advice literature which was widely popular in the eighteenth century. She was viewed as a novelty by some, an inspiration to others, and for those who came in contact with her unwavering resolve and unflappable beliefs a nuisance.

It was after Wollstonecraft's death that her personal reputation became an issue in evaluating her written work. Speculation about Wollstonecraft and the painter Henry Fuseli, her liaison with Gilbert Imlay, and her suicide attempts fueled the critics.

So what specifically is in her works?

Wollstonecraft's themes are still on the forefront of discussion:

- Communication between the sexes ·

- Long-term partnership in the place of marriage ·

- False refinement cultivated unnaturally · Economic independence ·

- The freedom to express desires without derision or loss of dignity ·

- Single parents ·

- Parents as caregivers, not outsiders ·

- Midwifery (pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding, parental bonding) ·

- Integrating private needs with familial responsibilities · Holistic healthcare ·

- Children's questions answered truthfully ·

- Sex education ·

- Right action comes from within – from an educated capacity to make judgments ·

- Rights transform external conditions of people's lives, nature offers a chance to shape from within ·

It is not Wollstonecraft's work so much as it is HER, her personality that is revolutionary. Wollstonecraft's genius evolved with her work. Here is a woman who created and maintained the freedom to shape her own life; a woman with authenticity in her voice and actions, resolve in her pen. Here was a woman who wanted to independently support herself. Injustice and exploitation were unacceptable. Wollstonecraft was not born a genius, she became one.

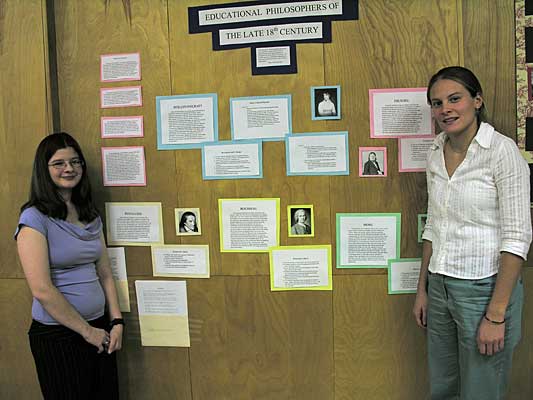

UMF students prepared a poster session covering various

aspects of the times,

critics, and the life of Wollstonecraft.

Chelsea Goulart, Chris Clark, Erika Hoddinott

Philosophy of the 18th Century

Philosophy of the 18th Century: Female Opposition to Mary Wollstonecraft - detail may be enlarged to read

Chelsea Goulart, Chris Clark, Erika Hoddinott

Philosophy of the 18th Century -- cont.

Sarah Estes, Edith Lovejoy, Becky McPhedran

Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley

Sarah Edes, Abigail Green, Heather Richards, Heather Lusky

Domestic Abuse

Leigh Eldredge, Angeliz Hernandez, Melissa L'heureux

A Brief Study of Women in the 18th Century

A Brief Study of Women in the 18th Century - detail may be enlarged to read

Kimberly Poole, Erica Emery

Educational Philosophies of the late 18th Century

Educational Philosophies of the late 18th Century - detail may be enlarged

(shown) Nathan Ellis, Samantha Smith (not shown) Michelle Urbanek, Amy Laprell

The Institution of Marriage in the 18th Century

The Institution of Marriage in the 18th Century - detail may be enlarged

Erin

GallagherHow Children Were Treated in Mary Wollstonecraft's Time - 1700's

Sara Kinsbury, Sarah Bunn,

Michelle

Derouche,

Elizabeth

Gane,

Polygamy in Different Religions and Cultures

Following the presentation the audience was invited to examine the three volumes of essays.

|

Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark - 1796 |

A Vindication Of The Rights Of Men - 1790 |

The photographs of the books by Wollstonecraft may be used freely on non-commercial sites (no advertisements). Please provide a link to this page with the image. Images of the poster sessions may not be copied, distributed, or otherwise published elsewhere.

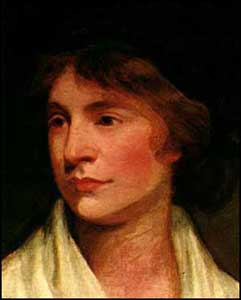

Wollstonecraft portrait from Wikipedia

.

|